ASSAULT ON GEMEINSCHAFT

PART 5 OF LESSONS FROM THE GERMAN “HOMETOWNS”

This is part of a series on how the history of German hometowns constitute an episode in the longue durée of the phenotype wars. New readers just entering at this point, who want to understand the phenotype wars, should read my new book on the topic, and those who want to situate this series, should see the introductory installment.

Last instalment, this series explored how the German hometownsmen deliberately fought against the encroachment of French Enlightenment spatialism upon the temporalist morality and culture of the German hometowns. Both commercial colonization and the nascent managerial class’s imperial bureaucracy were the pincer moves in this assault on hometown gemeinschaft. This long battle in the phenotype wars came to a head in the 19th century, as a series of circumstances began the erosion of German hometown temporalist autonomy.

The key crux of the constant struggle between the temporals of the German hometowns and the spatials of the imperial bureaucracy centred on the concept of Bürgerrecht. Though this term is commonly translated into English as “civil rights,” that is a misleading translation. The implication in the English phrase is generally taken to be a right isolated upon an individual, bestowed by a sovereign legality. It has a distinctly universalizing implication. In the German hometowns, the connotation was quite different; it resonated precisely with the particularity of their distinctive pluralism. Walker explains it this way:

The Bürgerrecht meant something both more positive and more inclusive than we are likely to mean by civic right; and unlike the privilege, franchise, or immunity that a sovereign might grant a subject, it was communal, held by grant of one's neighbors. Local control over the Bürgerrecht and participation of the Bürger in the issuing of it was at the heart of the community; a town could undergo a change of masters without disruption while that power stayed in its hands and the Bürgerrecht remained what it was. It was the stem of the cloverleaf, uniting the three capacities of social man: citizen, workman, and neighbor. Consequently all those elements of membership had to be satisfied for the Bürgerrecht to be granted. A man's every transaction participated in all three areas, so that even to speak of them as three is something the hometownsman would have found odd: we see it by contrast with ourselves.

Several important implications arose from this distinctive form of Bürgerrecht:

…[to be] without citizenship meant to have no right to pursue a citizens' trade, usually no marriage and no right to an established home, no vote, no eligibility for office, no communal protection against the outside (or against citizens), and no share in community property.

Often outsiders were forbidden to own immovable property in the town, and citizens were forbidden to sell such property to noncitizens (or even rent living quarters to them without special permission), so that physical property itself while not held in common had a strong communal cast.

Not only was it hard to get into a community, it was hard to get out…To renounce citizenship one had to pay an emigration tax: something on the scale of 10 per cent of a citizen's property.

Such onerous real social and material costs entailed in both leaving one hometown and entering a new one, while no doubt offensive to the high-mobility sensibilities of hyper-individualist spatially hegemonic regimes, such as ours, were essential in ensuring the high levels of stability in hometown population and cultural norms, so deeply valued by temporalist sensibilities. It was indeed then this Bürgerrecht which became the inflection point of contention in the power struggle between the temporalist hometowns and spatialist imperial bureaucracy, and other movers and doers, as the 19th century unfolded.

Walker goes into this century-long tug-of-war in far more detail than can be justified reproducing here. I’ll attempt merely to touch upon the key moments, providing some extrapolation where I believe it might be helpful. The first instance in the imperial assault on the hometown ethos is presented by Walker as coming from the emergence of the intellectual school of cameralism. This was a worldview that set out to recognize a fundamental harmony that tied together all the diffuse threads of an implicit totality. (Something like that.) A paradox was at work though as this theory applied to the German hometowns. Both diffusion and harmony were assumed to be essential operating conditions. As long as they were left to the abstraction of theory, these essential conditions could co-exist. Once cameralist axioms were applied to real-world social or political organization, that balance was no longer so workable.

…[cameralism] accepted the existence of all the discrete parts of German civil society, each with a set of detailed qualities and roles peculiarly its own, and worked from the assumption that if all of them could be comprehended at once an essential harmony among them would emerge above their apparent diversity.

The home towns were not important to the state fisc, and so they like other social elements that stood outside could live like monads, apart from one another and from the whole, as long as administration was fiscal only and the civil service a social abstraction.

The cameralist paradox could live quietly in the political incubator of the Holy Roman Empire. But when and where the state became strong enough to put the assumption of harmony among diversity and localization to the test, when civil servants reached beyond the fisc into the society itself, then the contradiction within the cameralist assumption became inescapable, and other solutions had to be found both in theory and in practice.

There's a great difference between the heuristic axiom of a full fitting together and the assumption that knowledge of such fitting were possible, in the face of all the nuance, changeability, and exhaustive scope.

Perhaps then it will be unsurprising to observe that cameralism, regardless of the intent of its originators, soon became an instrument of state, wielded against the local autonomy of the German hometowns.

[Cameralism] gave the state, seriously, a place very like God's, not in a sacramental way but as the place where omniscience and harmony had to be if they existed in the world.

Nearly every writer on cameralism has pointed out that cameralism was a state-sponsored science, developed by servants of the state or sympathizers with the state's purposes, and that its goals were fiscal: the accumulation of wealth to benefit the state's treasuries.

The leading force in the practical implementation of the statist logic of cameralism was Prussia, throughout the period of Walker’s book, the primary centripetal force. Spatialist forces had largely consolidated power in Prussia by the mid-18th century. Walker notes their distinctive approach to undoing temporalists institutions: “in local situations the pattern of seizure appears more political than systematic: they did not crush Prussian social institutions but infiltrated or bypassed them.”

Prussian administration posed two imperatives: first, that public officials know their districts thoroughly enough for their oversight to be genuine, accurate, and inescapable; and second, that they be detached from and immune to local influence and obstacles.

And behind all this of course lies the predictable inclinations of not only the spatialist’s enthusiasm for transgressing the borders and norms of other people’s institutions, but even the nascent managerial class’s self-importance as social engineering paternalist. In Walker’s words:

In the later eighteenth century there was a visible increase in the interest German administrators and academics took in the kind of economic activity associated with towns, even small ones. "Our century is an economic one," wrote Johann Christian Forster, professor of cameralism at Halle, in an "Outline of Rural, Town, and State Science," published in 1782; "We find even insignificant trades worth investigating, and try to find ways of perfecting them; we make systems, to raise the well-being of men."

As we saw in the last couple posts (see here and here), for the German hometowns, their liberty, as communal liberty, was rooted precisely in their ability to exercise communal control over mores, marriage, property, and trade. It was precisely such control that ensured stability, durability, homogeneity, and all the qualities of social trust and obligation that went hand-in-hand with those communal virtues. These controls, though, were precisely what the spatialists were determined to undermine on behalf of the movers and doers – their own phenotypes.

And, as we saw numerous times in my (must read!) new book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars – from the English conquest of the Scottish Highlands to the English enclosure conquests, to the eradication of peasant social and land institutions and customs during the French Revolution – this undermining of temporalist institutions and community was ever justified in the name of economic improvement. But the conflict, from the perspective of the temporals, was the imposition of economic “improvement” at the expense of cultural sustainability.

Walker illustrates these dynamics with reference to another influential cameralist Johann Justi:

He thought the study and teaching of Roman law had been "the first step Providence allowed us to take out of the thick fog of ignorance that everywhere surrounded us": now he would make it work in Germany.

Still he did not strike directly at the legal structures of towns and guilds. What he did, though, was more serious. He treated them as intermediate mechanisms to transmit harmony and order between individuals and the common weal…

He did not suppose “natural coherence" would come of itself, or at least not until the whole society was put on the right harmonious track. It was therefore the place of government to introduce the natural free conditions in which all would work together spontaneously: “to regulate each occupation and trade in such a fashion, as it would govern itself in its own self-interest if it had sufficient insight and understanding." The trouble came from insufficient insight into true self-interest. “If we wish to regulate the nature of economic movement correctly, then we must imagine how it would be if it perfectly followed its natural processes and found not the slightest hindrance from the state": the conditions of freedom to be achieved by close regulation.

As we also saw in my book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, notwithstanding the sanctimonious anti-state rhetoric of the individualists and free marketers, the powerful, regulatory state was the essential instrument of such supposed anti-statism, which in practice was really anti-intermediary institutions, anti-organic community, anti-kinship bonds, anti-guild, anti-tradition, etc. It was the state which destroyed the power of those intermediary institutions and practices, reducing their adherents to monadic, deracinated, atomized individuals. And, of course, such atomized individualism was the condition of perpetuated flourishing of the sovereign state. Not hostile alternatives, deracinated individualism and state sovereignty were in fact mutually dependent symbionts.

Understanding all this requires an even deeper understanding of the phenotype wars, which we can’t rehearse here, but is thoroughly explained in my new book. For now, it suffices to observe that we’re seeing another example of this same process unfolding in the story of the German hometowns. A nice passage from Walker, giving a sense of what was at stake in the extrapolation of Justi’s thought, is as follows:

…when laws are not observed the fault lies not with the citizen, who cannot always tell what is right and good, but with the government that has failed to give enough guidance toward true self-interest and the common weal; in Justi’s context at least (perhaps not only his), the non-responsibility of transgressors led to the total administration of civic life, as distinguished from judicial prosecution and punishment for specific breaches of law…there is nothing in Justi's theory of public authority and freedom that limits the scope of public authority. There is no suggestion that bureaucracy or its power will wither away. Justi did not really say that freedom itself would be achieved by close regulation. Closer to his meaning is that all Germans should come to share the ways of the movers and doers, of whom the civil servants were the pioneering element.

While Justi certainly never lived to see realization of his vision for a pervasive German bureaucratic state, his theory laid the foundation for the imperatives which informed spatialist thinking and politics during the 19th century. In a variety of times and places during that century, skirmishes in the phenotype wars broke out, as temporals and spatials struggled over the future definition of Germany – at least as understood from the terrain of that particular spot and moment. Unsurprisingly, leading the way in this regard was Prussia. Already, before Napoleon’s invasion, Prussia had introduced a land reform edict (1799-1805), presumptively liberating the peasants. For those who have read my book, there will be nothing surprising about this spatialist strategy, as explained by Walker:

…the way to individual initiative and high productivity on the land was individual private property, though this be social reform; the hometown analogy to agrarian reform would be the destruction of guilds and the Bürgerrecht system. The relative ease of change in the countryside had begun to turn the German civil servant from fiscal administrator to political and social reformer, in his own terms, before the revolutionary legislation in France provided its examples and Napoleonic power in Germany its opportunities.

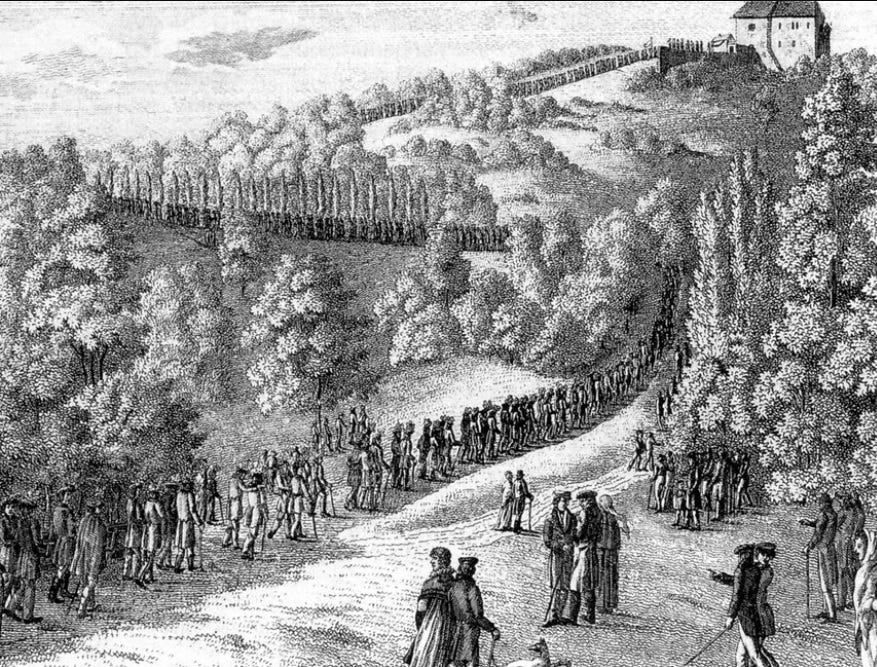

So, it can hardly be argued that such spatial shoots were not already creeping through the rock foundation of German communal (even federal) pluralism before the conquest of Napoleon. Still, Walker acknowledges the indisputable impact of conquest by the military arm of the French Enlightenment.

The Holy Roman Empire in its European setting had kept German politics since Westphalia out of phase, with its mechanism of localized political cycles and of balance; that had insulated the towns from the world, had fostered the development of baroque administration, and had kept the states from developing administration into reform. French power overturned the German balance by overturning the balance of Europe, and the internal effects of the overturn meant more to German politics than did the presence of French soldiers, governors, or military requisitions.

From Napoleon’s perspective, such decentralization as had characterized the Holy Roman Empire constituted a threat to effective delivery of the resources which he was exacting from it. Undoubtably, economic improvement was top of mind for the French Enlightenment emperor. As one might expect from what we’ve just seen above, though, such organizational impositions from the French occupiers found an eagerly receptive caste of spatial “movers and doers,” anxious to implement such reforms. Again, in Walker’s words:

…there was a real quid pro quo in the arrangements of 1805-1806, and a real community of interests: French support and protection was provided for the internal control the German governments wanted and which in turn was needed to generate the military and financial contributions Napoleon wanted.

Illustrative of the sea-change, which was initiated as a result of the new, French Enlightenment occupation of Germany was how those circumstances impacted the direction of German scholarship – which of course, going back to cameralism of the 18th century, had been a driving force in laying the predicate for spatialist expansion. Walker emphasizes this point with reference to Hegel:

…in 1806 [Hegel] replaced the noble estate with a "general estate," Stand der Allgemeinheit, corresponding closely with the movers and doers of the eighteenth century, whom recent events were bringing to the forefront of German political life. It was an estate of generalizers, dominated by the civil service and distinguished by its separation from local Bürger and peasants. The merchant class, inasmuch as its activities freed it from "ties to the earth and to the locality," did not "realistically" belong to the Bürger estate, either socially or ethically; ''by his rootless character the merchant blends systematically over into the general estate, the estate of the officials." The world of learning was in it too, since officials "are simultaneously men of learning." The quality of personal ambition set civil servant, merchant, and scholar off from actual Bürger. Hegel ultimately sorted German social spirits or ethics into three: the peasant's ethic was trust, the Bürger's was righteousness, and the merchant's and official’s was "cold heartlessness, the hard law"…

All this though did not turn out to be the end of the German hometowns. As Walker tells the story, a combination of administrative frustration, as the aspiring bureaucrats found their efforts defeated by local institutional resistant, combined with the military defeat of Napoleon 1812-1813, led in to a third phase, lasting through the teens and early 1820s. This constituted a restoration of sorts, which saw local autonomy returned to the German hometowns. Meanwhile, the lessons learned by the aspiring bureaucrats was that establishing official sovereignty over the hometowns was not going to be sufficient; actual direct administrative control was going to be required.

A notable response to the latter concern was the effort to impose systematic reform of municipal constitutions, Municipalrecht. The reforms were adopted to replace the council and collegial government characteristic of the hometowns. In such cases, the office and title of Bürgermeister were abolished in favor of the maire, who stood in a direct chain of command from prefect and subprefect and who was appointed by the state or by electors named by the state. Where implemented the reforms ended hometown control over local police powers, derogating them to those exercising administration of such powers in the city and country. A kind of “movers and doers” invasion of the hometowns was attempted under the auspices of these and other reforms. As Walker describes it:

States also tried to appoint lawyers and merchants, where they could find them, into town councils. But that had never worked out; hometown leaders remained what they had been; and so strangers were deliberately brought in for the business of organization and reform – trained and ambitious newcomers, young men fresh from their legal studies, from the pool of the central civil service, as their numbers allowed, to clear up the self-centered, the corrupt, the sloppy procedures of native communal government.

Marriage permissions for minors? Tavern licenses? Dismissal of malfeasant local administrators of town properties and endowments? Permission for close relatives to sit together on Community Councils? Appointments to minor church and town offices? Decisions to allow periodic public markets, open to outsiders? All the practical administrative arguments for independent local procedures were made to support the powers not of the communities, but of local state officials. For anyone at all acquainted with the home towns, of course, these were far more than procedural issues. They were questions of substantive and even constitutional law, and so eventually somebody asked whether they should not after all be treated as legislation, not as administrative clarification.

Another assault on the integrity of the hometowns came from administrative orders that had state officials assign the homeless to communities, including hometowns. Additionally, the guildless were to be assigned guilds. And the state assigned licenses to unpropertied and untrained peddlers. In Bavaria, local guild monopolies, requiring consumers to patronize local guildsmen and forbidding outsiders to enter the local market, were abolished. Another major assault upon the integrity of the hometowns were attempts to undermine their control over marriage. Restricting marriage to those who’d proven themselves stalwart members of the community was determined counterproductive to economic improvement.

Again, as we’ve seen across all the installments of this series, all these powers had been essential to the German hometowns’ ability to maintain its traditional mores and stabilize its customary institutions. These latter were under continual assault through the first half of the 19th century in the name of justice, fairness, and freedom. Though, the operative assumptions about the intrinsic nature of such justice, fairness, and freedom were of course thoroughly spatialist ones.

Battling such assaults upon hometown autonomy was a continual game of Whac-a-Mole throughout that century. Again, the many instances are discussed by Walker in rich detail, but this summary is sufficient for providing a flavor of the ongoing battle. There remain a few more important developments in the 19th century German story of this battle in the phenotype wars which I want to give specific attention before we move on to the final installment of this series, emphasizing what I take to be a (if not the) key takeaway from this exposition of the much too neglected history of the German hometowns. Those last few developments will be fleshed out in the penultimate installment to this series.

So, to be the first to see that installment, once posted, please…

And if you know others who’d be interested in such ideas, please…

Meanwhile: be seeing you!