In the effort to keep as concise as possible the recent post summarizing my book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, I resisted the temptation to digress into some epistemological and methodological matters, which I find interesting and think are of some importance. Indeed, I think understanding them goes some way in recommending the phenotype wars model. While I successfully resisted the digression there, for those interested, I thought I’d briefly reflect upon some of those matters here. This might be one for the fellow theory geeks.

I think of myself as a historicist, and am happy to, and frequently do, identify myself that way. However, I too often neglect the fact that the meaning of that term is not self evident and in fact there are those who interpret and apply it differently — sometimes in ways exactly antithetical to how I intend the term to be understood. So, maybe a few words of explanation may be helpful.

All else being equal, the way I intend the term to be understood might be described as being the opposite of progressivism. Progressivism, of course, is not the same thing as progress. A historicist (as I’d use the term) could certainly agree progress exists. Though identifying such would require acknowledgement of a particular perspective through which some series of changes were moving in a preferred or otherwise stipulated direction. That would be progress. And certainly the progressive could accept such a definition of progress, but the progressive’s particular perspective would entail moving toward some immanent or valued telos.

And I think that would usually be the assumption in progressivism: there is some kind of telos toward which the events of the world are pushing. In their different ways, Whig history and Marxism are examples of such progressivism. In contrast, historicism focuses upon historical events, not as steps in a grander narrative, progressing toward some telos, but rather as a specific situational moment, with a vast range of contingent vectors bearing down upon any historical actor, which can push and pull in multiple directions. For the historicist (at least, as I’m defining it, here) it would never be sufficient to explain a historical moment or situation by reference to some assumed narrative of progress toward a transhistorical telos.

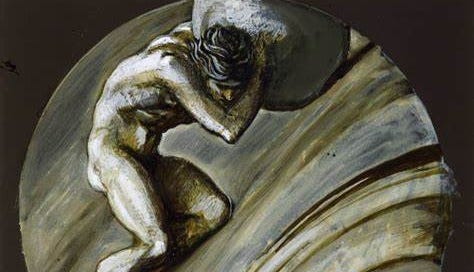

I believe that quite strongly. However, having said all that, those who read my recent post summarizing the phenotype wars model will appreciate that I’m not simply a historicist, and in fact I explicitly invoked the idea of progress — that immanent dynamics of the human condition were constantly pushing human societies “uphill.” However, while the notion of a telos usually is taken to imply an end point, an ultimate achievement, my progressive notion is one of climbing a hill to only go over the cliff at the top, and then to once again need to start uphill. It’s a rather Sisyphean historiography, in that regard.

Camus famously claimed that Sisyphus was free in those moments when he walked down the hill, before he had to start pushing the boulder back up. My Sisyphus, though, has no such opportunity. If the boulder is taken as a metaphor for human society, in my phenotype wars model it doesn’t roll back down hill, but goes over the cliff, taking Sisyphus with it. Where I would find a margin of freedom for the Corinthian king would be precisely in pushing the boulder up the hill. And this is where the historicism comes back into the picture. For, from my perspective, the hillside upon which the boulder is being pushed up is never quite exactly the same hillside.

Just as the old adage goes about never stepping into the same river twice, likewise my hillside is one composed of so many historically contingent variables that Sisyphus never goes up the same hillside twice. I’ve said that I prefer the phrase historical spirals to that of historical cycles precisely because it is true that you can never go back to the past — not exactly. The hillside is always different. And as an effect, in some ways, so too is Sisyphus also always at least a little different.

Now, I’ve obviously claimed that there’s some kind of immanent structure to the human condition — manifest in the reaction norm contained competition between the personality phenotypes I’ve identified as temporals and spatials. That is why the long term direction of human history is generally uphill progress. But the path up the hill is always contingent upon specific variables that give rise to the situation of that particular hillside, in that particular historical moment. Consider this comparison, if it’s helpful.

Europe mounted the full hillside, from the fall of Rome, through the “dark ages,” eventually to the next spatial revolution — e.g., reopening of intercontinental trade routes, the emergence of the state, and the Age of Discovery — in approximately one millennium. On the other hand, as we saw in the last post, from the earliest settlement of the Nile river region, it appears to have been closer to three millennia until Egypt entered its first spatial revolution. Part of the difference in these journeys is explained by the particular historical context of each case.

Presumably at least part of the explanation for that difference lies in medieval Europe’s ability to rediscover and build upon that lost Roman legacy, which included in many cases the literal building upon the physical infrastructure left by the Romans, in the way of towns and roads. But, of course, as often discussed on this Substack, undoubtedly included in such an appeal to that legacy was a major role played by the renaissance of Roman Law. Egypt of 5000 BC had no such legacy to appeal to or build upon. However, during the first intermediate period, they did have such a legacy to build upon, which surely contributed to them getting a new foothold on the hill in less than two centuries, on way to the Middle Kingdom.

So, while, yes, I can be called at least a structuralist (if not exactly a progressive) it is very much a historicist kind of structuralism. A prospect, I appreciate, that would drive structuralists and historicists alike just a bit crazy. That though I think is one of the strengths of the phenotype wars model. There always can be found evidence and arguments to support both structuralist (even progressivist) and historicist models of historiography. My analysis marries these approaches into a common model, which draws upon the strengths of each, while avoiding the tendency of both to lapse into narrow epistemological dogmatism.

As a final metaphor for this post, perhaps useful, would be the concept of guardrails. I certainly agree that the immanent dynamics of the human condition tends to push human societies up the hill. (Though, of course, the historicist in this cooperative endeavor would point out that not all human societies enjoy the conditions to advance very far uphill.) And certainly we might perceive there to be a deep structure to all that which acts as guardrails: ever guiding our societies uphill. However, these are widely spaced guardrails. There is considerable room for lateral movement, even as we inevitably, inexorably move up the hill.

All that movement, influenced by changes to the physical or mental terrain, from the last climb uphill, can result in all manner of unexpected movement and action between the guardrails. All of that is the stuff of history. None of that, though, of course, changes the fact that that deep structure — that immanent dynamic of the human condition — does ultimately drive progressing societies up a hill. A hill always ultimately topped by a looming cliff.

And, incidentally, though I won’t go into it here, it’s worth mentioning that this model of the phenotype wars, with its interlocking dialectics, not only offers a resolution of the age old epistemological conflict between structuralist (and progressive) and historicist explanations, but it also resolves that other age old ontological conflict between determinism and agency (or free will). But we’ll leave that for another day.

And another day there will be. So, if you want to see what such a day may bring, and haven’t yet, please…

And as ever, if you know others who might enjoy the hijinks we get up to around here, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!