THE CATHOLIC GUILD CORPORATISM OF KETTELER

PART EIGHT: GUILDS, OLD AND NEW

This post is an installment in a longer series on Guilds, Old and New. To review a full index of all the installments to this series, see the introductory, part one of the series, here.

In the previous post covering Ralph Bowen’s book on German corporatism we saw how the German philosophers – particularly the Romantics – theorizing against the French Enlightenment’s emphasis upon rationalism, individualism, universalism, and progressivism, offered a different history and foundation for German society and nation, build upon social organicism, and the integral role of corporations as manifesting and integrating such social organicity. In the next couple installments to this series, we’ll focus upon what Bowen identifies as the most successful social movement, Social Catholicism, at implementing these philosophical ideas within German society of the latter 19th century.

The movement of Social Catholicism embraced guilds and corporatism not merely as a matter of economic justice and compassion for the working class (though that too), but simultaneously as a means to achieve that end without lapsing into either of the destructive alternatives offered within contemporary German political culture: liberal individualism and Marxian socialism; and as a means to to preserve Christian values in the face of an onslaught of hedonism occasioned by the spread of modernism, commercialism, and industrialism. In the end, much like the North America populist movement soon to follow, this initially grassroots political and economic movement was eventually co-opted by electoralist passions which gradually drained resources and momentum, ultimately resulting in the defeat of the movement’s most ambitious aspirations.

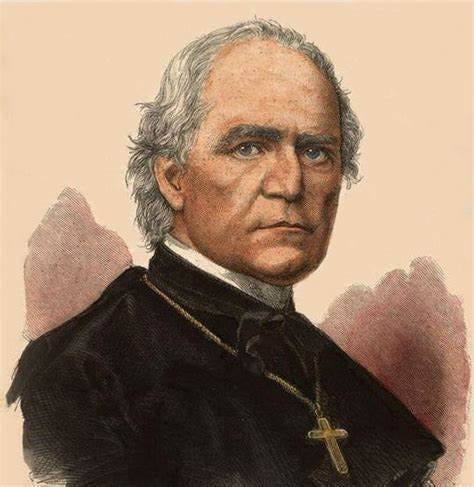

In this installment we’ll focus on the contributions to Social Catholic corporatism of its foremost advocate, Baron von Ketteler. In the next post, we’ll consider another key intellectual contributor to that tradition, Franz Hitze. First, we allow Bowen to sketch out the rough terrain of Social Catholicism’s embrace of corporatism, before turning to a more detailed discussion of the corporatist project and platform of Ketteler and his followers.

The churchmen, scholars, publicists, social workers and politicians who became the leaders of Social Catholicism were moved primarily by religious and humanitarian impulses, fearing the destruction of Christian faith and morality unless ways could be found to alleviate the popular misery and to moderate the social antagonisms that laissez-faire industrialism was producing.

As the machine extended its conquests, there occurred a corresponding decline of household and handicraft industry accompanied by a marked worsening of the position of many skilled craftsmen who saw themselves increasingly threatened with displacement from their former position of relative economic independence.

In the long run the effect of these developments was to promote the emergence of trade unionism on the English model, but for a considerable period in the 1880's and 1890's there persisted a strong tendency on the part of surviving handicraft workers to cling more tenaciously than ever to traditional guild forms of organization as a last line of defense against the factory system.

Some 9,000 guilds were still in existence in 1886, the majority in eastern Germany. Of the 35,000 master craftsmen in Berlin in that year, 13,000 (employing 40,000 journeymen and apprentices) were guild members, and as late as 1890, more than a quarter of the master craftsmen of the Reich were still enrolled in Handwerkerinnungen.

[The proponents of Social Catholicism] attacked Manchester liberalism for its defense of [industry’s abuses of labor] and for its one-sided emphasis upon materialism and individualism. At the same time they rejected revolutionary socialism on the ground that its outlook was equally hedonistic...

Christian brotherhood and charity were to replace selfishness, aid was to be extended to the lower classes in the form of private benevolence and social legislation, and the workers themselves were to be organized for "self-help" in corporative bodies that would protect their legitimate interests without encroaching up on those of other groups, thus promoting a sense of social solidarity in all classes.

A key figure in the development of this Social Catholicism was the Bishop of Mainz, Wilhelm Emmanuel, Baron von Ketteler. His profound influence on the generation that gave initial form to Social Catholic corporatism was widely acknowledged at the time, including by Pope Leo XIII, often crediting Ketteler with the ideas that informed his own influential Encyclical, Rerum Novarum. Ketteler’s disciples persistently and energetically propagated his ideas throughout western Germany’s seminaries during the 1860s and 70s, influencing a generation of younger clergy. He was decisive in showing the path of this third way, between liberal individualist hedonism and socially destructive Marxian socialism.

Bowen lays out some the key highlights in the development and form of Ketteler’s thought:

Ketteler could see no remedy for the social evils generated by this philosophy [liberal individualism and materialism] short of bringing about a complete inner conversion of all men to the "true political and social wisdom" embodied in Christianity. Only then would governments cease their dissolving activities, and only then would selfishness and lust for material gain cease to dominate men's lives. Only then would new forms of social and economic organization, "corresponding to present-day needs," come into being.

The French Revolution had only intensified a trend that had long been evident, and Rousseau had been the true heir of Louis XIV when he exclaimed, "Liberty? Why, it is nothing but the despotism of reason!"

Without promising every man the delights of an earthly paradise, however, Ketteler thought that much might be done in the way of moral and material betterment of the lower orders through a fuller development of what he called "the principle of association." This principle, which was as old as the family institution itself, was "a natural law of humanity, provided that it seeks to realize the ends marked out for it by Providence." "The Germanic spirit, more than any other, has developed this principle, whether we consider the family, the village commune, the parish or the craft organizations and guilds."

Recovery of this salutary “principle of association,” in the context of current German society, Ketteler believed was most effectively and parsimoniously recovered through institutions of civil corporation, reflecting in this regard the earlier propositions of Hegel and the Romantics on civil society, and the organicist social philosophy of Fichte (see here). And, interestingly, anticipating the contributions of Max Weber, at least in the estimation of Bowen, Ketteler recognized the role of a monist sovereign bureaucracy in imposing the crushing conditions of contemporary workers.

Bowen quotes Ketteler in this regard:

It is not without a deeper reason that we apply the word "body" to certain associations. The body represents the most perfect union of parts bound together by the highest principle of life – by the soul. Hence we call those associations "bodies" or "corporations" which have, so to speak, a soul that holds their members together.

Ketteler was convinced that the "pulverization process" set in motion by liberalism could be arrested and reversed only by the inauguration of a universal scheme of labor organization, the fundamental unit of which would be a "corporation" including all members of a single profession and binding them together in a spirit of Christian brotherhood. He placed a demand for the formation of such associations at the head of his program for solving the "social problem," holding that the state had the double duty of furnishing by means of legislation the necessary assistance to the working class in organizing a corporative structure, and secondly of protecting the worker and his family by law against unjust exploitation. This intervention would bear a purely transitory character however, because, once established, the new corporations would enjoy autonomy within their respective spheres and well defined constitutional bulwarks would secure them against bureaucratic invasions of their rights.

In keeping with his organicist social theory, Ketteler not only recognizes the role of federalism as integral to such corporate pluralism, but acknowledges the need for at least some extent of heterachy to make such corporations effective, while still seeing such layered association as the means to not rip apart but more closely bind society. Again, quoting Ketteler:

Let the various unions form district federations. These can serve as courts of appeal for their members, administer their common funds and form a connecting link between the unions and the state.

Then secure recognition of the district federations by the state as legally competent bodies.

According to Bowen:

The object to be pursued by these labor organizations was not, as their socialist leaders insisted, to promote the class interests of the workers; on the contrary, truly corporative bodies would aim "not at war between the worker and his employer but at peace on equitable terms between the two."

Bowen goes on to discuss the expanse of Ketteler’s influence.

During the next few years Ketteler's views achieved very extensive circulation, particularly among West German Catholics, He gathered around him at Mainz an enthusiastic group of Catholic scholars, students and publicists, and his teachings were taken up and propagated by a rapidly growing band of followers throughout western Germany.

In the field of labor organization the pioneer of Catholic trade unionism had been Adolf Kolping (d. 1865), a priest of working-class origin who had been a fellow student of Ketteler's at Munich and who had been active in forming journeymen's societies (Gesellenvereine) since the early 1850's.

These organizations, of which there were more than four hundred at Kolping's death, were usually presided over by a priest, who was assisted by a council of sponsors (Ehrenrat) made up of prominent citizens. The program of activity discouraged interest in economic matters and was mainly confined to mutual aid, moral uplift and general education.

In 1879 the total membership of these Catholic workingmen's societies amounted to only 9,260.

...groups sprang up in neighboring communities, and in 1871 these were united in an organization for the whole province of Westphalia. This example was successfully imitated in the Rhineland, in Silesia and in Bavaria during the 1870's and early 1880's, and by 1896 the movement was able to claim a total of some 32,000 members.

The movement early established its own press, set up its own courts for arbitrating disputes among members and acted as intermediary between the peasantry and the large banks and insurance companies…

…subsequently it became vociferous in demanding increased tariff protection for agriculture.

So, even at this time, these Catholic workers’ unions, with their theoretical grounding in corporatist philosophy, has distinctly heterarchical tones. They seem at this time to have at least anticipated the North American populist movement, with its emphasis on the building of intermediary institutions (see here). However, through Bowen’s telling of the story, it seems that Social Catholic corporatism also anticipated arguably the major error of the North American populists, in overly investing in the role of an electoralist party as the instrument of its political ambitions.

In the case of the Catholic corporatists, especially the inheritors of Ketteler’s legacy, the party in which they (understandably) invested was the German Center Party. It was originally founded in 1870 to defend Catholic interests against Bismarck’s Kulturkampf. So it might be understandable why the Social Catholic corporatists saw this new party as a potential vehicle for their goals of corporate pluralism. Much as with the North America populists, though, this shift to electoralism led to the frustration of the social pluralist movement they’d built

The genesis of this foray into leveraging electoral politics was arguably in a private brochure by Ketteler:

In a brochure written in 1871 for private circulation among Catholic political leaders (although not made public until two years later), [Ketteler] outlined a program of action which was accepted by Windthorst, the [Center] party's first chief, and which formed the basis for much of the Center's political strategy during the next decade. Point XII of this program was entitled "The corporative reconstruction of society," and demanded that "the state should give back to the working classes that which it has taken away from them – a labor constitution." This "labor constitution," he thought, should be based on the following principles:

1. The desired organizations must be of natural growth; that is, they must grow out of the nature of things, out of the character of the people and its faith, as did the guilds of the Middle Ages.

2. They must have an economic purpose and must not be subservient to the intrigues and idle dreams of politicians nor to the fanaticism of the enemies of religion.

3. They must have a moral basis, that is, a consciousness of corporative honor, corporative responsibility, etc.

4. They must include all the individuals of the same vocational estate.

5. Self-government and control must be combined in due proportion.

So, again, we see Ketteler’s emphasis upon guild or union corporations as autonomous and heterarchical.

Still, Bowen also emphasizes that Ketteler’s theory was not reliably consistent in all such matters and so understandably this lack of theoretical homogeneity likely contributed to political and activist moves at cross purposes. This also likely played some role in the problems that beset Ketteler’s Catholic corporatism as it was increasingly transformed from a pluralist social movement into an electoralist political program.

The body of ideas which Ketteler bequeathed to his successors was not altogether homogeneous, and when the political leaders and social theorists of German Catholicism attempted to apply his teachings they did not at all agree as to what parts to emphasize. Some placed a higher valuation on the medieval and romantic heirlooms in the collection – the conception of society as a pluralistic union of organically differentiated members, for example – from which they deduced the need for a thorough reconstruction of society that would give adequate recognition to its "functional" or occupational groups. Others (and at first these were in the minority) leaned toward a more "reformist" point of view, believing that it would be sufficient to work for the gradual elimination of the more flagrant abuses of laissez-faire industrialism, relying up on benevolence from above, self-help from below and a limited application of state socialism "from outside."

...[those inheritors] shared Ketteler's misgivings about universal suffrage, though they made a great point of accepting the constitution of 1871, appealing especially to its guarantees with respect to religious freedom. They agreed with him that the democratic franchise of the Empire was preferable to the oligarchical three-class system of Prussia, but they insisted that it was only a lesser evil and possessed many faults of its own. The ideal form of popular representation, they considered, would take as its basic unit not the individual but one of the "natural" groups in society.

Despite their virtually unanimous sympathy for the general corporatist viewpoint, however, the Center's leaders studiously refrained during the first years of the party's existence from putting forward any specific demand for corporatist institutional changes. Their energies were absorbed in combating the Kulturkampf.

The party's first programs had moreover laid particular stress upon "the preservation and strengthening of a powerful middle class in town and country.”

March, 1877, when the Conservatives brought into the Reichstag a motion expressing the desire of master craftsmen for a more stringent regulation of apprenticeship and of journeymen's Arbeitsbücher. The Center's leaders, though they approved of the particular aims of this bill, decided to introduce an alternative bill embodying their idea of the scope and function of labor legislation in general. The text of this bill bore a striking similarity to Point XII of Ketteler's program of 1871.

This alternative bill, according to Bowen:

...called upon the government to lay before the Reichstag a project of law looking toward the amendment of the Industrial Ordinance (Gewerbeordnung) of June 21, 1869, re-enacted for the Empire, which had established complete occupational freedom in the North German Confederation. The Center's motion specified further that this new law should include clauses designed to "protect and improve the position of handicraft workers by placing restrictions up on occupational freedom and by regulating the obligations of apprentices and journeymen toward the master craftsman." [It] went on to demand "a revision of legal provisions relating to the freedom of movement," and closed with a plea for the speedy establishment of a new system of guilds.

Bowen then quotes from the bill:

In order to make good a grave injustice, to avert a great peril, to restore labor, the source of all well-being, to its rightful honor, it is necessary to reverse the direction heretofore followed. . .Real improvement in the situation can result only from the inauguration of a scheme of corporative associations.

Somewhat amusingly, from the perspective of those concerned with the role that guilds specifically, and corporate pluralism generally, might play in a regenerating of temporalist institutions and culture, Bowen notes that during the bill’s three-day debate the liberal parties and the Social Democrats, making common cause in opposition to such a revision of the regime of occupational freedom, characterized the Center's position as "the negation of all our modern institutions...of all modern political development." From a temporal restoration perspective, that would be of course precisely the point.

This attempt within the electoralist paradigm to advance the cause of Catholic corporatism, though, however lackluster it may have been, proved to be both unsuccessful and ultimately the final gasp of such ambitions.

At the close of the debate the bill was referred to committee; it was never heard of again.

After 1880, and especially after 1890, emphasis shifted away from the corporatist elements in Ketteler's theoretical legacy and came to rest squarely upon meliorism. Instead of seeking thoroughgoing reconstruction of the economic and social order the new policy of the Center aimed almost exclusively at the gradual removal of specific abuses.

So, much as with the North American populists, the investment of corporatist energies into electoral politics proved to be a dead end, which ultimately squandered the emotional and material resources of the ambitions of intermediary institutional pluralism. However, Bowen observes, almost like an Indian Summer, preceding the descent into an autumn decline of Catholic corporatism: that movement enjoyed its most comprehensive theoretical statement at its political twilight.

...[the] corporatist viewpoint had received its most comprehensive theoretical elaboration in 1880, almost at the exact moment when the tide began to run strongly in the opposite direction, with the publication of Franz Hitze's Capital and Labor and the Reorganization of Society, a work which, despite the subsequent desertion of its author to the meliorist camp, furnished much intellectual support to corporatist enthusiasts in the Center and in the Social Catholic movement at large.

So, it’s that intellectual contribution to Catholic guild corporatism of Franz Hitze to which we turn our attention in the next installment of this series on Guilds, Old and New. So, if you don’t want to miss that soon as it hits the press, and haven’t yet, please…

And if you know other folks who’d be interested in our deep exploration of the history of guild pluralism, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!