THE MAKING OF ORGANIC COMMUNITY

PART 3 OF LESSONS FROM THE GERMAN “HOMETOWNS”

This is part of a series on how the history of German hometowns constitute an episode in the longue durée of the phenotype wars. New readers just entering at this point, who want to understand the phenotype wars, should read my new book on the topic, and those who want to situate this series, should see the introductory installment.

The last installment concluded with reference to the means by which the German hometowns protected their gemeinschaft nature in the face of external threats to their autonomy and identity. Understanding such dynamics requires a deeper dive into the constitution of these hometown organic communities.

So, what was it exactly that characterized these German hometowns. Walker makes an important observation when he says: “There had to be regular reciprocal relations between leadership and citizenry; from that political fact resulted the extraordinary integrity and coherence of the community.” As we’ll see later, I’ll draw upon that dynamic as essential to the model of communal freedom illustrated by the German hometowns. Walker identifies three main constitutional bases to town governance: Customs, Privileges, and Statutes.

By constitution l mean here those documents and accepted practices that described a town's rights of self-government and its particular internal institutions and procedures.

A Privilege usually was sovereign acknowledgment of a Custom, and a Statute was a written compilation of Customs and Privileges.

Custom was the name and justification for laws and procedures for which no written basis could be found, and a town's own constitutional basis normally resided in its Customs…They became explicit only when they were adduced to support some legal decision or legislation.

…for a Custom to have the force of law it had to exist as a conviction of right and it had to be expressed in practice. Moreover, that conviction of right and that practice could not come from an individual or a transient aggregate of individuals; Custom had to be a communal understanding – Gemeinüberzeugung – of how the community did and properly ought to run.

The important feature of Customs as hometown constitutional bases was not their unspecified age but their very specific localism and communalism. Inasmuch as they relied neither on principles of Roman law nor on general legislation by a sovereign (nor on any serious notion of natural law), they were almost by definition idiosyncratic; they drew their force from the community's individuality and gave force to the defense of its autonomy.

…most of the vital life of most communities did in fact follow patterns that were unwritten, informal, and unsystematic.

For regular readers of this substack, and those who have read my new (must read!) book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, this description of the German hometown by Walker will be immediately recognizable as the essential organic community, Weber’s gemeinschaft, and Innis’ time biased society. It is in the tradition of the Scottish, rather than the French, Enlightenment tradition, with its emphasis upon custom and shared communal experience as the essential ingredient to a communally cohesive governance. As Walker says, invoking the influential Otto von Gierke: “Because Custom, as Gierke said, had to be embodied and accepted by the whole community, the resort to it had the effect of integrating town government with the community as a whole.”

This situation Walker contrasted to the imperial towns under the direct influence of the Empire:

Imperial town constitutions depended more on Privilege and Statute, in writing, emanating from sovereign authority; their political and juridical situations favored that kind of derivation. Customs by contrast did not descend from sovereignty but arose from community, and so did the authority they rendered.

To think of institutions as patterns of civic behavior, and to discern them in events and social relations rather than in legal diagrams, is to approach the kind of understanding of the community that the hometownsman had…

Walker provides an elaborate description of the governing practices and structures that underpinned these temporalist operations of the German hometowns. Space constraints here will only allow us to touch upon some of the essential features involved. As just mentioned above, Walker evokes a tradition of communal freedom, which I’ll elaborate in a future post to this series. Consequently, of course, we wouldn’t expect the German hometowns to be governed by something that would pass the sniff test of “democracy” according to contemporary standards. At the same time, those governance structures were not merely aristocratic, either. As I’ll elaborate in that forthcoming post, Walker I believe recognized that the German hometowns manifest a completely different model, a temporalist one, for thinking about freedom and popular autonomy (not to be confused with popular sovereignty – at least not in any contemporary, conventional sense).

The hometowns were run by councils composed of dignified members of the town. Distinguishing such council members for being dignified, as we’ll see, is entirely on point. Personal character was an important dimension of legitimacy in public life within the German hometowns. Walker elaborates:

Certain families tended to persist in community leadership over the generations, and older families had an advantage over newer ones. But their positions were not prescriptive, or only vaguely or partially so; they could be lost in a generation. Ruling circles were not closed, although a new family might take a generation or two to develop an accepted position.

The base of a hometown leader's influence was with the community, and depended in the end on the possession of qualities – family tradition included – that his fellow townsmen respected and needed more than they envied or mistrusted them, and that is a long way from hereditary right. Established political families came persistently to lead hometown regimes because they chose to and because they operated that kind of regime weIl, and if they ceased to do either they disappeared from high office.

Such town councils might have locally specific names, such as one town Walker examines in length, which called its council the Herrenstube. This literally translates into something like the gentlemen's chamber. As Walker emphasizes, though, this was not a council of nobles, or a "patriciate." As we’ve seen though, membership was accessible not through birth, but rather profession or office. “It included town officers, and those citizens who ‘earned by the pen’ or who lived from independent incomes.” This criterion distinguished such members from the crafted-based guilds. This exclusion though was simply because the guilds were already a structural part of the hometown government.

All the recognized guilds were represented on the councils. The standard number of guilds seems to have been nine. Then there were an additional nine dignified members of the town, bringing the council membership up to eighteen. There was also an inner council, with a more executive function (if I understood correctly), which was composed of five of the eighteen. The representation of the broader population then came through their membership in their guilds. All townsmen, who were not independent of wealth or income were part of a guild. Consequently, the guilds were the institutions that bound the citizenry to the administration of government. Walker’s description of conflict resolution within the hometowns is telling:

Should there be conflict between the town executive magistracy and the Eighteen, immobilizing town government, the nine electoral Fives were supposed to mediate, a procedure approaching intervention by the citizenry to resolve conflict; should that fail the citizens were to be assembled by guilds, to vote by majority within each guild on the issue at stake. Should this last expedient fail, the town faced open conflict between government and citizenry; hometown institutions had broken down, and there had to be recourse to outside arbitration or the imperial courts.

…at no point did anyone in the town have the power to overrule one side and enforce a decision.

…differences within the leadership were resolved by gradual appeals down through the levels of influence, expanding progressively toward involving aIl the citizenry if need be.

So, again, we get the rough outlines of a form of government, which would hardly pass the sniff test as “democracy” in our current understanding of that term; the hometowns’ emergent governance processes though had evolved to protect communal freedom and an autonomous people – if not exactly a demos. In fact, what these communal institutions entailed were the ethos and practices of pluralism. Newer readers, who want to better understand this temporalist tradition of pluralism, should consult my new book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars.

Another point that will be important for fleshing out an alternate model of popular autonomy, from Walker’s insights, is the tremendous importance that the German hometowns placed upon maintaining an elite class which remained firmly rooted within the town: resisting the danger of inter-town elite alliances. Again, a couple passages from Walker illustrate the point. For instance, he notes that, in the imperial towns:

Patrician families married among themselves, or with other patrician families from other places, and rarely with the lower elements of their own cities (although this happened). By contrast, hometown leadership, however stabilized and influential at home, rarely intermarried with similar leading elements from other towns. Sometimes a hometown leader had married outside, but apparently no more often than other citizens had, and I suspect in fact less often; commonly his children married members of other Bürger families of the community.

The sustainability of such municipal pluralism depended upon keeping the ruling elite firmly rooted in the town. Inter-town elite alliance gave rise to institutions that would ultimately serve to insulate the leadership class from local control.

And a point that Walker emphasizes repeatedly throughout his book was just how vigorously and aggressively exclusive the hometowns were. As we’ll see, it was the impact of the nascent managerial class, tip of the spear of the spatials, which was especially (though hardly alone) targeted, for their mobility, as a threat to the hometown’s continuity and durability.

High education among families in leading political positions (here ignoring inferior and transitory figures like parsons, clerks, and schoolmasters) may be the clearest sign of the absence or breakdown of community integrity. It is a useful perspective from which to view hometown complaints about “learned doctors," and Roman law, and government by scribblers – and from which to view the attitudes of the learned toward the home town.

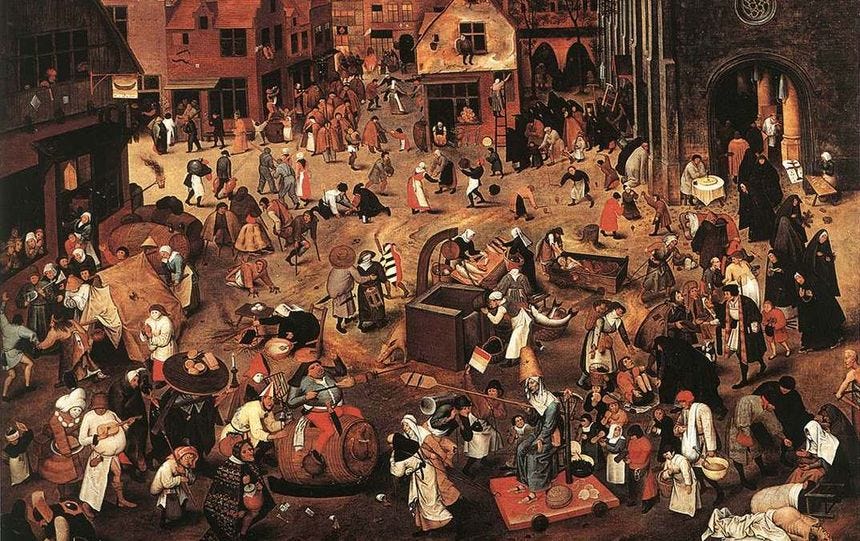

In contrast to such suspicion of the university educated, as we’ve seen, the craft guilds were the foundation of hometown life. As obvious as this might be economically, and in addition to their political importance discussed above, this was equally true at the level of culture and morality. I’ll provide here a lengthy list of passages from Walker – with occasional context or color added by me – which provide a sweeping set of insights into just how foundational the guilds were to all those dimensions of German hometown life.

The guild constitution, to which Flegel had subscribed, provided that wife as weIl as master must show proof of four irreproachable grandparents;

[The guilds’] "social location" was the home town; only there – not in the city and surely not the countryside – could the guilds assume so broad a role and still remain basically economic institutions. Only in the context of the home town is it comprehensible how the time of the notorious "decay" of the early modern German trades guilds should have been the period probably of their greatest power to impress their values and goals upon the society of which they were components.

As occupational groupings within the community – of butchers, shoemakers, carpenters, and the rest –guilds supervised the recruitment, training, and allocation of individual citizens into the community's economy, and their economic character placed its stamp upon hometown morality and the nature of citizenship itself. As primary political organizers of the citizenry…, they bore political and civic factors into economic practice and moral standards. And finally as moral and social watchdogs they saw to the quality of the citizenry – … the honor, of the hometown workman and Bürger.

Guild statutes often set forth rules of guild life in remarkable detail, although of course much guild activity took place informally and unrecorded – which is not the same as to say quietly, by any means – and in conjunction with the cousins and brothers on the town councils and in the other trades.

The Overmasters decided internal conflicts, spelled out rules, levied fines and imposed minor punishments, administered guild finances and properties, saw to the inspection of masterworks prepared by candidates for mastership (though this might be done by a specially appointed inspector), and generally represented the interests of the trade, within the community and to the outside if need be.

A guild court composed or dominated by these officials [Overmasters] could expel any member who did not accept its decisions, and thus foreclose his practice of the trade; and frequently such a court punished members for civil or criminal misdeeds like theft or adultery, on the grounds (if anybody asked) that the transgression had brought the trade into disrepute, so that the trade must punish the offender to clear its name.

The Overmasters were custodians of the Guild Chest, the Lade, a kind of ark of the guild covenant symbolizing the guild's corporate authority and autonomy, repository of its official documents and secrets, ceremonially opened on the occasion of meetings of the membership.

[Plenary meetings were] held regularly – quarterly as a rule – but extraordinary meetings might be called to consider special problems, like a serious infraction of the rules by one of the members…that threatened the interests of the guild.

As membership in one of the official guilds was a prime ticket into one of the hometowns, the guilds’ enforcement of moral standards was an essential instrument of enforcing its temporalist norms. As the historical period under examination passed, increasingly the hometowns’ faced a pincer move, between an influx of migrants, considered untrustworthy, because of their lack of any history or stake in the community, on the one hand; and on the other hand, growing imperial bureaucracies tried to push the hometowns into acceptance of a more generalized notion of individual rights, which contradicted the temporalist communal freedom of the hometowns. Controversy over the exclusion of those of illegitimate birth became a touchstone of this conflict with the imperial bureaucracy. Walker dedicates a good deal of page space fleshing out this dimension of guild morality enforcement and its relation to the defense (and constitution) of the German hometowns’ norms and ethos.

…political controversy within communities…made [the guilds] work and even fight for the kind of political community that would defend its autonomy against the outside, a fight to blend the political with the economic commune. Guild organizations were hostile to any separate governing or mercantile patriciate; they were Bürger agents of the cycle that tended constantly to restore the home town, and Bürger elements of the equilibrium. They were an integral part of the incubator whose outer form was the Holy Roman Empire.

What the state with its aim of economic development conceived to be abuses were precisely the foundations of the guildsmen's honor; and the correction of abuses was for guildsmen the incurrence of dishonor.

…the guild [practiced] denunciation and ostracism, to punish practices which the state for its part considered good economic policy. If, for example, a Prussian guild under state pressure accepted "dishonorable" members – the illegitimate, the sons of shepherds or of state officials, or French immigrants – then other guilds in that trade would declare the Prussian guild and town dishonorable, and journeymen could come to work there only at the risk of eternal disgrace, which could exclude them from finding work or achieving mastership in any guild that considered itself honorable.

Consequently the supply of journeymen and hence of potential new masters was reduced in places that had relaxed their standards under official pressure, frustrating the intent of state (or patrician) authorities in forcing the relaxation.

The main preoccupation with legitimacy of birth, which extended by easy stages into questions of sexual behavior and social background, had a reasonable foundation in the domestic character of community and economy…

The guilds were then a vital instrument in assuring the moral standards of the hometown remained high. An additional filtering instrument was the access to citizenship as vetted by the town council. The Bürgerliche Nahrung was a property qualification, which Walker translates as the "citizen's livelihood," and was an essential condition for acceptance into the hometown. It went beyond mere property ownership, though, as Walker expands:

Bürgerliche Nahrung as prerequisite for citizenship was not a static property qualification nor even a requirement of technical skill. These might contribute to it, but they were not its essence. It meant the economic security and stability of the solid citizen, a trustworthy man because he was committed to local society and totally reliant upon it; like Eigentum, it combined economic and civic status into personal quality…

Another trait considered, was Ehrbarkeit (often also called Redlichkeit), which Walker translates as decency: “[it] could not be clearly defined or objectively ascertained, like wealth, skill, or performance; it was something sensed as it was displayed and received within a community of whom all shared the same standards.”

Ehrbarkeit meant domestic, civic, and economic orderliness and these were undermined by the promiscuity and irresponsibility implied by illegitimate birth. Legitimate childbirth resulted from sober and responsible intention to have a child, whose conception bore the community's sanction; illegitimacy implied the contrary.

It might be argued that moral sanctions were directed less against loose sexual behavior as such than at its social consequences: the foisting upon the community of persons with uncertain origins and uncertain qualifications for membership.

…[this] was the morality of the hometownsman, not the mobile and sophisticated high bourgeois. Hometownsmen did not have the multiple standards and compartmentalized lives that so many modem moral and social critics deplore: one set of standards for church on Sunday, another for relations with friends, another for business relations. They were whole men, integrated personalities, caught like so many flies in a three-dimensional web of community.

At this point, we can take stalk a bit. The hometown world Walker is describing is one of deep temporalist values: rooted in strong, exclusive community, and sexual mores that assured both highly conscientious character and commitment to the community’s social norms. These were organic, gemeinschaft, communities in the deepest sense, which were suspicious of strangers, not just because they posed an uncertain risk to the community’s norms and standards, but because they were rootless. And that rootlessness itself was a red flag for flawed character.

Of course, from the perspective of a spatialist, such a person was merely refusing to be boxed in by old ideas and irrational boundaries – social and geographic. The temporals of the German hometowns, though, unlike so many temporals today, understood the threat that such spatials posed to their communities, and established this elaborate set of standards and institutions to protect themselves from such spatialist forces.

To be clear: at this time, the slowly growing bureaucracies which however (initially) tentatively challenged these temporalist norms and institutions, did so not on the basis of some appeal to intrinsic human rights, or the like, as we’d expect today, but primarily on the grounds of economic improvement. This passage from Walker should be read through the lens of the standard spatialist appeals to “economic improvement” seen in so many of the historical examples discussed in my new book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars: e.g., the English pacification of Scotland, the English enclosures, the French Revolution.

The structure and working sphere of the guilds show the place of economic institutions in hometown life. There is no doubt that the guild system was unsuited to economic growth and social mobility, nor that, if growth and mobility are taken to be the norm, it inhibited them. But that was the obverse of the guilds' vital function in communal society and politics.

The German hometowns and the guilds which largely constituted them were not apologetic in presenting themselves as bulwarks against “economic improvement,” insofar as such improvement entailed their town’s cultural, communal, social disintegration. They were bulwarks against spatialism from the earliest days of the French Enlightenment. We’ll explore that aspect of the German hometowns in further detail in the next installment to this series.

So, if you want to be sure to know about that next installment soon as it’s posted, please…

And, if you know of anyone else who’d be interested in these topics, please…

Meanwhile: be seeing you!

Enthralling.