In the next little while I’m going to transition into a greater focus on what might be called cultural critiques and analyses of the spatial revolution. More specifically, analyses that address what we might call the spatial revolution’s endogenous-turn: beyond (exogenous) territorial expansion to cultural and psychological penetration. Each in its own way a form of spatial colonization: a turn we’ve already foreshadowed with Carey and Melbin’s discussion of the spatial revolution’s colonization of time — particularly, in the latter’s case, of the night.

Many of the authors to be addressed would likely characterize their position as critique, but an analysis is always implied and it’s this latter dimension I’ll be more focused upon. When reviewing the broad sweep of cultural critique of capitalism, while there is undoubtedly a “conservative” tradition of such, I think probably a far more expansive tradition lies in the broad school of Marxism.

This focus of course raises the interesting matter that there are serious impulses within the Marxist school that are properly identified as temporalist. Some of the key figures of the Frankfurt School, for instance, had strong temporalist tendencies. Given what we already know from Michéa, about the roots of early 19th socialism being deeply rightwing (see A Plea for Time), it hardly should be surprising to discover this tendency within the Marxist school. It is true that Marxists tend to rhetorically position their critique as being against “capitalism.” And, certainly, as we saw in Grossi’s examination of the spatial revolution in European law, capitalism was a major pillar in those developments (see here).

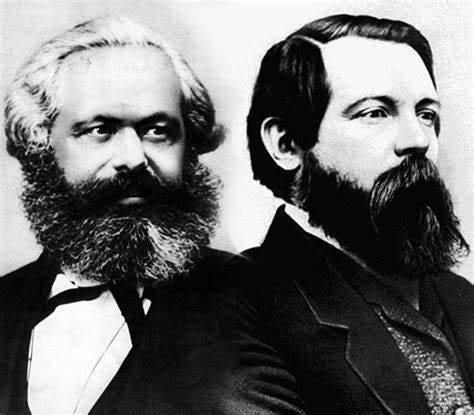

However, as I’ll demonstrate below, momentarily, notwithstanding their rhetorical posture, upon close examination, it is quite clear that what they’re really critiquing is the spatial revolution. Now, there’s certainly differences. Horkheimer (and possibly Adorno), clearly had antipathy straight up toward capitalism for its role in the destructiveness of the spatial revolution. On the other hand, others, like Marx and Engels harbored a grudging respect for capitalism, and what they called the bourgeoisie. (More on that term, below.) But, even at that, their historical sociology of capitalism remained uncompromising in its analysis and description of the effects of the spatial revolution. And it was indeed the spatial revolution they were addressing – strategic nomenclature notwithstanding.

So, it seemed maybe a good place to begin – this leveraging of the temporalist strain within the Marxist school for a cultural analysis of the impacts of the endogenous-turn of the spatial revolution – could be no better chosen than with, arguably, the beginning of it all: The Communist Manifesto. As we’ll see, contrary to what most of you probably thought that short little book was really about, if viewed through the lens of temporalism, it’s perfectly clear that the first part of the first section is precisely a description of the historical consequences of the spatial revolution. So, let’s have a look.

A quick prefatory remark on Marx’s discourse is in order. As always with Marx, his language was carefully chosen to obscure the distinction between capitalists and his own ventriloquist masters constituted by the managerial class. The use of the term “bourgeoisie” serves just such a purpose. It can be, and historically has been, applied to capitalists as well as the lawyers, professors, administrators, etc., that constituted the early expression of the managerial class. (For a more thorough unpacking of all this, see my book, The Managerial Class on Trial.) As such, this bit of nomenclature is typical of Marx’s obscurantist discursive strategy. It is valuable to keep this in mind, rather than lapse into the common mistake of imagining “bourgeoisie” as an unproblematic synonym for “capitalist.”

Right from the start, then, in The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels conceive capitalism as a profoundly revolutionary force, in which not only technology but all of society itself is remade into a new order that is distinctive for its erasing of traditional boundaries and values:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form, was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.

The final couple phrases there, of course, are just conceits of Marx and Engels, implying that only consciousness of class struggle constitute the “real conditions of life.” That conceit, though, is hardly necessary to appreciate the extraordinarily revolutionary effects they attribute to the bourgeoisie, and thereby capitalism. The revolutionary side of the equation hardly seems subject to dispute. What I want to emphasize here though is the extent to which this revolution is a revolution in the remaking of space.

These social and technological manifestations of said revolution are precisely expressions of revolutionary expansion, both globally and civilly. That is, Marx and Engels conceive the forces they’re analyzing as revolutionizing both the space of the geographic world, as well as the culture and life space of Gemeinschaft, with its traditions, rituals, and customs. Beginning with the former revolutionizing process, we let them speak for themselves:

Modern industry has established the world market, for which the discovery of America paved the way. This market has given an immense development to commerce, to navigation, to communication by land.

The bourgeoisie, during its rule of scarce one hundred years, has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all preceding generations together. Subjection of nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalization of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground – what earlier century had even a presentiment that such productive forces slumbered in the lap of social labour?

The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.

And as though foreshadowing the spatial revolution within the civil life of the regions of capitalism’s own origins, and incidentally mimicking Schmitt’s conception of the spatial revolution’s European nomos of the earth, Marx and Engels point to how this geographic expression of the spatial revolution involved the transgressing of other world societies’ cultural, social, traditional boundaries. Such traditional societies are bound together into a Schmittian nomos by this revolutionizing of geographic space1:

In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations.

The bourgeoisie, by the rapid improvement of all instruments of production, by the immensely facilitated means of communication, draws all, even the most barbarian, nations into civilization. The cheap prices of its commodities are the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls, with which it forces the barbarians’ intensely obstinate hatred of foreigners to capitulate. It compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image.

Independent, or but loosely connected provinces, with separate interests, laws, governments and systems of taxation, became lumped together into one nation, with one government, one code of laws, one national class interest, one frontier and one customs tariff.

Throughout their analysis we see these common themes of industrialized communication, expanding across the globe (the girdling of the globe, in Hobsbawn’s nomenclature), with its bourgeois capitalism – their avatar of the spatial revolution – acting as a social acid upon the historical and traditional ways of life among the world’s diverse nations. Given these observations, it should hardly be surprising that Marx and Engels point to the same spatial revolutionary processes within the societies which gave rise to this bourgeois capitalism:

The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honoured and looked up to with reverent awe. It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers.

The bourgeoisie has torn away from the family its sentimental veil, and has reduced the family relation to a mere money relation.

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. It has pitilessly torn asunder the motley feudal ties that bound man to his ‘natural superiors’, and has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous ‘cash payment’. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value, and in place of the numberless indefeasible chartered freedoms, has set up that single, unconscionable freedom – free trade. In one word, for exploitation, veiled by religious and political illusions, it has substituted naked, shameless, direct, brutal exploitation.

I hope these passages are sufficient to make the case that right from the start, despite lacking Schmitt’s lens through which to view the events and dynamics they described, Marx and Engels understood their bourgeois capitalism as in fact the expression of a spatial revolution. Driven by the newly industrialized means of communication, they saw that spatial revolution expanded across the earth, with as little regard for geographic obstacles as for traditional or cultural ones.

And no less than this powerhouse force colonized the geographic world, so too they saw it colonize the social world. Through its commericalization and commodification of social and familial life, and relentless demand for the free trading of all such determined factors of production, it crushed the traditional intermediary institutions and customs which had previously protected the social world from the radical universalism of such revolutionary spatialist ambitions.

Of course, what Marx and Engels deeply lacked in all of this, despite their crude appeals to “consciousness” was a psychology of what underpinned the values-driven action of the various actors whom they analyze. This though was simply the state of human knowledge at the time; they can hardly be faulted for not knowing what nobody else knew. It is that lacuna in their understanding which leaves them vulnerable to the crude economism characteristic of so wide a swath of the Marxist school. I can’t help wondering, if they had understood the essentials of personality psychology, whether they might have groped their way towards an understanding of the phenotype wars. They were really so close.

Be that as it may, it is not the case that the entirety of the Marxist school all succumbed to crude economism. And while the cultural Marxists had their own theoretical shortcomings, they did help provide a far deeper critique and analysis of the social, political, cultural, and technological impacts of the spatial revolution. And it is those writings toward which I’ll be turning my attention in some forthcoming posts. So, if you don’t want to miss all that, and haven’t yet, please…

And if you know others who might enjoy and appreciate the kind of thing we get up to around these parts, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

It is worth bearing in mind here that they published this manifesto in 1848, at the very beginning of the dramatically extended reach of the spatial revolution as documented by Hobsbawn (see here), and so in fact seeming to invoke more still the world of primitive spatial expansion discussed by Innis in relation to the beaver fur trade (see here).