CORPORATISM IN FEASTS, CRAFTS, AND BENEVOLENCE

PART TWO: GUILDS, OLD AND NEW

This post is an installment in a longer series on Guilds, Old and New. To review a full index of all the installments to this series, see the introductory, part one of the series, here.

We start off with reviewing some of the key observations on the history of the guilds provided by the exhaustively documented intellectual history provided by Antony Black. Black’s book1 is “a history of medieval and modern political thought from the viewpoint of the guild and of values which have been associated with it.” It’s more a historiography than a history. Additionally, an important aspect of this historiography is an exploration of the longstanding confrontation between the values and preferences of liberalism and the corporate pluralism of the guild legacy. Nonetheless, by way of exploring these dimensions of intellectual history he does provide an extensive history of the guilds. While I’ll touch upon the former concern of Black’s, it is primarily the latter which receives attention in this subset of installments to this series on guilds, old and new.

In quick summary, Black emphasizes that the “connection between guild and polity was especially pronounced in the medieval cities.” In that context, he dwells upon the ordinary mentality of townsmen. Liberalism, through the theoretical device of civil society, “made triumphal progress during the Renaissance.” Yet, the values of guild and commune renewed their strength during the Reformation. The Reformation re-awoke communal stirrings in Germany and produced the original articulation of the guild-town ethos. Though, he concludes that there only eventually emerged a fleshed out philosophy of guilds in the thought of Bodin and Althusius.

Particularly interesting, I found, were Black’s many insights on the origins of the guilds. I’m guessing like most people familiar with the guilds, but having failed to look deeply into their history, I'd always associated guilds to crafts and tradesmen. I'd certainly been aware of fraternities, friendly societies, and discussion or drinking clubs, but thought of these as separate entities with distinctive histories. Instead, Black argues that the guilds arose precisely out of such sources, both in their ancient forms, as well in their persevering Germanic form. We’ll give him some space here to express both sets of claims2:

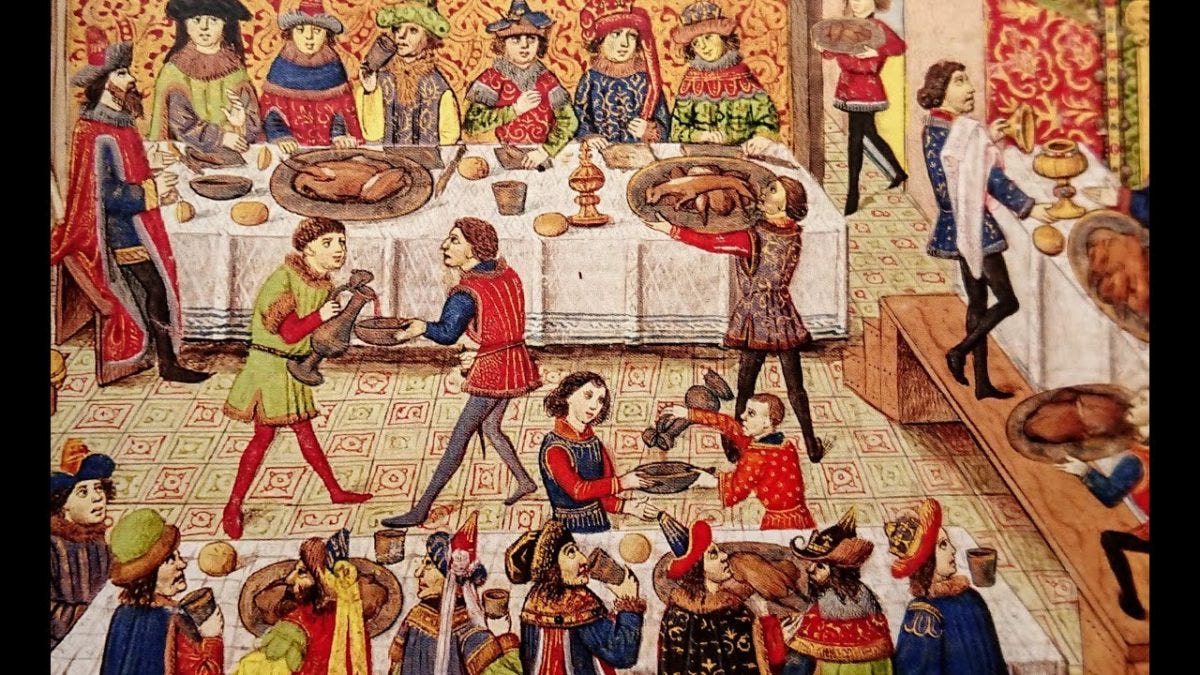

...some time before AD 450, the word gilda signified a sacrificial meal. This was accompanied by religious libation and the cult of the dead. The sacred banquet, signifying social solidarity, was, and remained throughout medieval times, ‘an essential mark of all guilds’, which were sometimes actually known as convivia.

Male drinking clubs played an important role in ancient Greece. The Roman collegia (also called corpora, sodalitia), which included social clubs, burial societies and cultic groups, went back ‘earlier than recorded history’, being mentioned in the Twelve Tables as an imitation of a Greek model.

The development of political clubs in the late Roman Republic led to a general suppression of colleges under the consulate of Cicero, and again by Caesar. Augustus stabilized their position as friendly societies for religious purposes, burial and other forms of mutual aid; a distinction now emerged between ‘licit’ and ‘illicit’ colleges.

In this set of observations we learn about the socially diverse nature of the origins of the guilds in antiquity. This hardly should be surprising if we understand that medieval guilds, right into early modernity (as we saw in Mack Walker’s books on the German hometowns), while organized around crafts, embraced the full spectrum of human communal activities – social, cultural, religious, and economic. So it should hardly be surprising to learn the origins of guilds in antiquity were rooted in precisely such a diverse set of concerns.

We also learn here a little about the source of their eventual oppositional character in relation to the aspirations of the monist sovereign, distinguished by the monist as licit or illicit. Also we are offered a prospect for deriving the name guild, in the sacrificial, sacred meal of the gilda. When Black turns his attention to the more recent history of the guilds, in the medieval German period, another possible vector in the naming of such societies is introduced, and we find a new wrinkle in the conceiving of the guilds as forms of what might be called civil families.

During the Germanic settlement of northern and western Europe, from the fifth to the tenth centuries, the guilds played an especially important role as a form of social organization not dependent on blood ties but sacred in character, providing security as ‘artificial families’.

...guild in the Germanic languages (more often, in this context, spelled gild) originally meant ‘fraternities of young warriors practising the cult of heroes’, and then any group bound together by ties of rite and friendship, offering mutual support to its members upon payment of their entry fee (geld).

Known as gildonia, confratnae or convivia, they were at first most common in lower Germania, Frisia and the low Countries. They were mutual support groups an alternative to feudal relations in an age of acute instability when something more than family bonds was required.

Black goes on to provide insight into what might be called the politics of the guilds, both from the internal and external perspective. In the case of the former, their unique form of political association was wedded to the history of mutual aid and cultural ritual which, as we’ve just seen, was integral to the history of the guilds.

Their members were not necessarily of equal social status, and they might include women; but within the group the oath was taken not to a single leader or lord but to each other. Their functions were now extended to all kinds of mutual protection: burial funds, support for poor members or dependents of deceased members, an insurance service in case of fire or shipwreck.

...guildsmen must support one another in their quarrels and vendettas, and protect each other from outsiders, even if they have committed a crime.

Rules stipulating maximum hours and so on comprised a large part of guild regulations, and it was with the enforcement of such rules, together with the maintenance of standards, that guild courts were primarily concerned.

Guilds settled disputes among their own members, exercising over them a kind of jurisdiction.

These social guilds provoked the opposition of lords and bishops, of the Lombard kings and Carolingian emperors: they were accused of orgiastic rites, drunkenness and lasciviousness. Their rites were suspect to the church, their secrecy to lay rulers too. They made claims, quasi-legal in character, which were bound to stand in the way of feudal lordship and any would-be state. The mutual oath made them appear dangerous; as Cicero and Caesar had banned the Roman collegia as politically subversive, so medieval rulers from time to time charged guilds with the crime of sworn conspiracy (coniuratio).

In these observations we note the seeds of what I’ve called heterarchical pluralism, as we see the guilds tending toward becoming jurisdictions of legal sovereignty, even (to varying degrees) self-consciously opposed to the aspirants of monist sovereignty. In the process, that tendency contributes to the heterarchical pluralism of the medieval constitution, as earlier discussed at length on this Substack (see Legal Pluralism series).

Black provides analysis of how the distinctively craft based guilds of the medieval period widely maintained the functions of the above discussed social guilds:

The first known Medieval European craft-guilds appeared around 1100 in Italy the Rhineland and the Low Countries, and they proceeded to spread very quickly over western Europe.

[There is a] continuity with the Germanic social guilds in view of shared features: the mutual oath, insurance against sickness, poverty and death, ceremonial drinking and communal feasting. This seems highly probable for northern Europe, where many craft-guilds called themselves ‘fraternities’ from the start...

A historical development of note in these processes was the gradual separation of the craft guilds from the merchant guilds:

...there would appear to be considerable variety over Europe: there are cases of crafts agitating for corporate recognition and also of towns determining the number of permitted craft associations, usually in collusion with the larger merchants and the more powerful crafts themselves.

The economic policy of the merchant guilds and early towns was aimed at maximizing the volume of trade and the consequent benefits to the town and its own merchants: all goods passing nearby must go through the town, tolls must be paid, a certain amount of handling must fall to local men, and so on. The craft-guilds on the other hand were concerned with maintaining a steady volume of business for their members. Their chief aims were a satisfactory standard of workmanship and a fair price for its products, and the restriction of ‘the number of apprentices a master might keep, the hours he might work and the tools he could use.’

Black also noted, in keeping with what we saw in Mack Walker’s discussion of the topic, that the craft guilds promoted sound workmanship and security for their members, often in the form of restricting access and opposing the interests of unskilled, non-guild laborers. Those emergent spatials, whom Walker had characterized as “movers and doers.” (Discussed throughout the series, but for example see here.)

This concise overview of the guilds’ origins set us up nicely then for discussions to follow. Next up, we’ll look at the setting of the guilds within the complexities of medieval legal pluralism. That, of course, is the post that never quite found its way into the discussion of legal pluralism. So, if you finally want to be right up to date on that discussion, and haven’t yet, please…

And if you know other folks who might be interested in the topics discussed on this Substack, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Antony Black, Guilds and Civil Society in European Political Thought from the Twelfth Century to the Present (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1984).

All Black’s copious in-text citations have been removed for purposes of quotation here.

this is so fun!