This post is part of a lengthy series exploring the world of legal pluralism, particularly (though not exclusively) as it was grounded in the world of the medieval constitution. For a full index of the installments so far, see the introductory post, here.

Legal pluralism is found throughout the world of temporalist regimes. Indeed, a major factor involved in the eclipse of temporal regimes by increasingly spatialist hegemony is the erosion of legal pluralism, under the weight of legal monism. However, given its direct lineage connecting to us and our world, it seems to me that our focus in unpacking legal pluralism should center on its roots – for us – in the medieval constitution. (As I’ve emphasized earlier, “constitution” in the lower case, does not refer to a written document, but to traditions of norms and custom which constitute the legal order. See, here.) However, given the state of things, it seems to me that a series on legal pluralism, particularly as set in the medieval constitution, needs to begin with a refutation of a certain American conceit.

The influential American mythology is that the “revolutionaries” overthrew the yoke of the king (though it was parliament which imposed the much objected to Sugar, Stamp, and “Intolerable” Acts). And I guess to make the “revolution” even more heroic, and vaguely Robin Hoodish, the mythology painted the king as a cruel, tyrannical dictator. So, the American conceit, which given the intellectual and cultural imperialistic reach of America, has spread elsewhere by contagion, has persisted that king = monarch = dictator/tyrant.1 There are so many errors in this equation it would be daunting to attempt correcting them all in a single post. Consequentially I'll be selective in my comments. But if we're to understand pluralism in its medieval context, this American conceit needs to be cleared up.2

Across the vast expanse of European history hardly any king was truly a monarch, which literally means the rule of one. (A valuable distinction which, Kern below, doesn’t observe.) If we restrict ourselves to English history for the moment, arguably Henry VIII is the only crown to exercise something like tyrannical power. Though Mary was pretty bad, but brief. Elizabeth may have largely retained her father’s powers but did not exercise them with the same tyrannical might. And, maybe because she didn’t, that’s about it. Certainly, the early Stuarts aspired to such absolutism, but they never achieved it. And the latter one wound up losing his head for his trouble.

In fact, while I’ll focus in these two installments on the medieval constitution, Nicholas Henshall, in fine detail, illustrates that even the modern crowns, even Louis XIV himself, were not the absolute monarchs they’re made out to be. The modern era French kings remained constrained by traditions and institutions. And often the governance of their realms was accurately described as a manner of federalism. Indeed, as Henshall shows, the very notion of absolutist monarchy was from the start a propaganda trope.3

And to be clear, in saying that virtually no European kings were truly monarchs, I’m not even considering the fact that those few kings who could make a credible claim of being monarchs in the literal sense still ruled with the assistance of a clique of often highly valuable advisers and agents. (It would be meaningless to consider Henry VIII’s regime without reference to Thomas Cromwell, or Louis XIV’s without Jean-Baptiste Colbert.) What I’m referring to instead, is that the medieval constitution – which yes was certainly eroding by the 16th century, though as noted by Henshall lingered on in many ways and places in early modernity – involved a wide range of constraints upon the power of kings. To the degree that many may have aspired to dictatorial power, they were constantly constrained and, when required, resisted.

This story is told in many places. I’d particularly recommend though an excellent, concise little book by Fritz Kern, Kingship and Law in the Middle Ages.4 Kern illustrates that – while obviously there will be outliers to any sweeping claim – kingship as a medieval institution, to maintain its legitimacy and in many cases its survival, was compelled to submit to a range of constraints upon its power, both formal and practical. These included expectations of being under, what Kern calls, the old (customary5) law (literally the opposite of being sovereign!), and the institutional and cultural acceptance of the fully legal right of resisting, and even deposing, kings who failed to remain within the law, or violated the rights of their subjects. I’ll quote Kern at length here to provide a flavor of his argument.

…popular will was an essential element in the foundation of government, and consequently the concept of Divine Right could not in this period be based simply upon right of birth, as it was later, under the domination of the principle of legitimism.

…the early medieval monarch, however exalted his theocratic position, was always at the same time bound by earthy fetters.

We shall, therefore, describe next how far the ruler, according to the legal ideas of the early Middle Ages, was limited in the free exercise of his princely will, and was obliged to respect legal limitations outside his own control.

Afterwards we shall show how individual subjects, the whole community, or else some authority set up by them, reacted to any overstepping of these limitations, and to what measures they resorted for resistance and protection

Established for the maintenance of existing legal conditions, the State was not designed to pursue the active and aggressive policy which is characteristic of the modern State. The king who best represented mediaeval ideals was not the ruler bent upon extending his frontiers, but the righteous and pious prince who ruled not only unselfishly but also with proper regard for the limits of State action

Germanic and ecclesiastical opinion were firmly agreed on the principle, which met with no opposition until the age of Machiavelli, that the State exists for the realization of the Law; the power of the State is the means, the Law is the end-in-itself; the monarch is dependent upon the Law, which is superior to him, and upon which his own existence is based.

In the Germanic State, Law was customary law, the law of one's fathers, the pre-existing, objective, legal situation, which was a complex of innumerable subjective rights. All well-founded private rights were protected from arbitrary change, as parts of the same objective legal structure as that to which the monarch owed his own authority. The purpose of the State, according to Germanic political ideas, was to fix and maintain, to preserve the existing order, the good old law.

"Law" was the living conviction of the community, which, though not valid without the king, was yet so far above the king that he could not disregard the conviction of the community without degenerating into lawless "tyranny."

It is true that the Frankish kings, in their Capitularies, created much new law on their own initiative. But the new laws all remained technically folk-law – in the sense that the community "found" them, and the monarch "ordained" them.

…the mediaeval Germanic notion of law, in spite of its preference for the old law, did not in the ultimate analysis envisage any downright unalterable rules; it claimed only that no change in existing conditions should take place unilaterally, without the free assent of those whose rights were affected. The monarch ought never to interfere arbitrarily with well-established subjective rights, upon which, according to the opinion of the time, the whole fabric of the objective legal order was based.

…through this consensus…every legal innovation and statute is brought into accord with the conservative principles of customary law. This notion of consent implies the fixed idea that the enacted law – whether old or new in substance - live in and is accepted by the legal consciousness of the community, that it is therefore a part of the law of the people; for legally speaking, there is only one law, It is the law which the community acknowledges by custom or express declaration, and which the monarch ordains.

Amid the fluid and fluctuating rules and usages of the early Middle Ages for securing assent and agreement, the single decisive principle stands out that the command of the prince created true law only if it was in harmony with the free conviction of the people. How the monarch satisfied himself of this, was in any particular case his own business; but nothing relieved him from the necessity of seeking assent in one way or another.

Cases are not rare in which a monarch subsequently declares even one of his own decree to be invalid because ordained contrary to law, or in which such a decree is condemned by his successor.

As Kern explains, it was not sufficient that the community understood the king to be constrained by the law, but it was necessary that the king acknowledge the legal and political fact of such constraint. The Church played an important role in all of this. The Church constituted an important constraint on kingly power, requiring oaths of loyalty to the customary law. Indeed, the very legitimating premise of the king deriving authority from God was provided through the Church at the price of coronation being held ransom to the king’s vows of obedience to both God and the old law. Again, quoting Kern at length on these royal vows:

The princes of the Middle Ages frequently acknowledged that they were bound by the law. Since in the Middle Ages, no fundamental distinction was drawn between ethics, custom, and law, this limitation possessed, as we should say, not only a moral or natural validity, but also a validity in positive law.

Solemn promises by a prince before he began to rule were here and there customary as early as the period of the folk-migrations, but apparently there were no durable rules with regard to such undertakings, until clerical influence gave rise to fixed traditions. This seems to have occurred first in the Visigothic kingdom. When, in the ninth century, the ceremonies for the inauguration of a king came under ecclesiastical influence in the Frankish kingdom, the solemn undertakings subscribed by the monarch before his coronation assumed a form which, with certain modifications, set the standard for Western monarchy.

The form and content of this royal vow varied; in particular, the duty of the monarch to maintain customary law, to uphold the legitimate rights of individuals, and to safe-guard the possessions of the State, was frequently enjoined in more detail and definition. But the actual wording of the vows was not of first-rate importance, although at times care was taken to define the ruler's duties in concrete terms.

The decisive fact was that the monarchy in the very act of its establishment solemnly placed itself under the law.

Only after the king had taken the oath was he elected by the acclamation of the assembled people. This was merely a formal election. When it followed the oath, it expressed the fact that the subjection of the monarch to the law was a prerequisite for his acceptance by the people.

Kern also emphasizes that even with such oaths, the subjects’ side of the covenant between king and subject was not one of obedience, but rather one of fealty, in which obligations are mutual. But even the fealty, properly speaking, is not so much to the king as to the law, which binds them both.

…the oath was not merely a symbol of royal duty; it was at the same time a legal act -- affirming this duty.

The subject, according to the theories of the early Middle Ages, owed his ruler not so much obedience as fealty. But fealty, as distinct from obedience, is reciprocal in character, and contains the implicit condition that the one party owes it to the other only so long as the other keeps faith. This relationship, as we have seen, must not be designated simply as a contract. The fundamental idea is rather that ruler and ruled alike are bound to the law; the fealty of both parties is in reality fealty to the law; the law is the point where the duties of both of them intersect.

He reiterates in another place in the book the importance of not confusing this fealty oath as a contract.

It was easy to consider the limitation imposed upon the king by the oath and the homage of the people the elements of a contract, in which it was tacitly or expressly stipulated that one party was bound to the other so long as each upheld the contract; and this view was argued from a very early date…the fact remains that the legal bond between the two – is not accurately reflected by the notion of a governmental contract. The relationship between prince and people is not the same as that between partners in an agreement at private law. Rather both are bound together in the objective legal order; and both have duties towards God and the "Law" which cannot be traced back to a contractual idea.

Parenthetically, though I won’t expand upon the point in this post, Kern’s warning his reader off the mistaken notion that the medieval constitution entailed what we’d think of as a contract – perhaps invoking Hobbes for some – dovetails with rather important points we’ve previously seen emphasized in the work of Robert Nisbet. As Kern succinctly puts it:

...the theory of absolutism arose not from the mediaeval doctrine of Divine Right, but from a different world altogether – from the Romanist doctrine of government based upon contract.

Further on he adds:

In later centuries, Roman law proved to be a veritable arsenal for absolutism in its fight against Germanic customary law. It played this same role – at times exaggerated but still of undeniable importance -- on its first appearance in the constitutional struggles of the Middle Ages in the early days of the Investiture Contest. The study of Justinian's law, which was just awakening to new life, and was probably stimulated by Gregory VII's command to search the libraries for ancient legal authorities, thus operated as a potent force in the struggle over the relations between monarch and people.

From a temporalist perspective, the deleterious impact of the Roman Law upon the medieval constitution is something I’ve discussed at length in my new book, A Plea for Time in Phenotype Wars, and is a topic we’ll return to later in this series. For now, though, let’s see Kern unpack the practical side of this constitution.

For, while the dynamics discussed above demonstrate a formal context entailing constraint of the kingly power. The skeptical modern mind, infused with the assumed virtue of official separation of powers mutually checking each other, would understandably ask about the practical implication of all this. Was such constraint merely formal? In which case, could it be real? Kern addresses this matter head-on.

…is [there] any power that may compel the prince to perform his duty, punish his breach of duty, and free his subjects from their allegiance. What guarantee did the commonalty in the early Middle Ages possess that the monarch would respect the limitation of his power by law?

The answer which Kern illustrates is the right to resist. A concept also deeply rooted legally in the medieval constitution.

…the right to resist an evil ruler came to be taught, it was not conceived of as primarily the right of a partner whose contract has been violated, and certainly not exclusively as a personal right of the subject against the ruler, but mainly as a duty of resistance owed by the citizen to the objective legal order which had been disturbed by the ruler and was now to be restored.

…the magnates, [the king’s] counsellors, became his natural enemies the moment he pursued a policy of centralization; for the position of the aristocracy rested upon its share in the regalia and upon the weakness of the central power.

If the monarch projected fresh undertakings abroad which required sacrifices, he had to put into motion the clumsy apparatus of negotiation and discussion with his magnates. A foreign policy not resulting from long-standing tradition was regarded as a private affair of the king or the royal dynasty, which concerned the nation as such either not at all or only with its own assent.

Though of course etymologically the words have different roots, from an English speaker’s perspective, the age of feudalism seems to be aptly named. Notwithstanding rural land holding arrangements, the medieval constitution was largely organized around the rightful exercise of feud, as means for mistreated subjects to pursue just compensation from the king.6

…to oppose force to the king's use of force was, according to the common legal creed of the Middle Ages. not only permissible but even in certain circumstances obligatory.

Kern acknowledges that the exercise of the right of resistance, taking up arms against the king, like the formal oath of the king prior to being crowned, was not always beyond reproach in the actual application, but still concludes on what is the key lesson to be taken from that right – notwithstanding the purity of its application in any specific case.

In these informal proceedings, it is very difficult to distinguish the use of force from the exercise of customary right, or treasonable insurrection from the flaring-up of legal feeling. And yet, questionable as were the motives in most cases where the right of resistance was exercised, the general conviction that the community's duty of obedience was not unconditional was deeply rooted, and no one doubted that every individual member of the folk "had the right to resist and to take revenge if he were prejudiced in his rights by the prince.”

…whether or not the individual was always able to justify his resistance to the satisfaction of subsequent generations, contemporaries were almost always willing to grant the possibility that a rebel was acting in good faith, under the pressure of necessity.

As Kern concludes, “Only the loyal king has loyal subjects.” Taking this idea to perhaps its logical conclusion, he observes:

The English barons in the fourteenth century gave this idea a modern formulation when they stated that their oath of fealty was due to the Crown rather than to the actual wearer of it – that is, to the unchangeable symbol of lawful magistracy rather than to the individual caprice of a particular monarch. Fealty so defined might, therefore, in certain circumstance be fulfilled on behalf of the Crown against the king.

…when the supreme judge upon earth, the king, denied right, there was only one lawful way of obtaining redress--namely, judgment of battle. The king was no exception to the general rule.

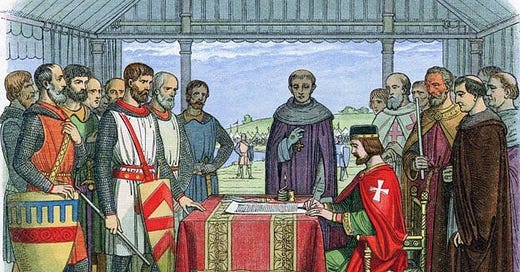

Finally, though Kern’s book has much more to say, on this and other aspects of the medieval constitution, I’ll just add one more interesting observation from it here. He explains that most of the mythology around the Magna Carta is misplaced. As should be clear from the above, any notion that it constituted a unique or remarkable case of a king’s subjects resisting his abuses, is simply without historical merit. Nor was it remotely remarkable that they extracted concessions from him. Nor even that such concessions were put in writing. Kern observes that if the famous events at Runnymede had a claim to distinction it was for none of these usual misguided celebrations. What was unique about it was that it appears to have been the first time the medieval constitution integrated a formal juridical structure and process to adjudicate and redress abuses of the law by the king.

What is the essence of Magna Carta, in virtue of which it has become a landmark in history? Not the fact that a king once again, as so often, admitted certain legal duties, and promised to fulfil them. Equally little the fact that once again the magnates, with weapons in their hands, extorted such an admission from an unwilling king. The only fundamentally new thing in the treaty which John Lackland concluded with his barons at Runnymede, is the establishment of an authority to see that the king carries out his obligations, and, if he fails, to coerce him.

Toward illustrating that point, Kern quotes from the Magna Carta:

…we [referring to King John] have granted all these concessions, desirous that they should enjoy them in complete and firm endurance for ever, we give and grant to them the underwritten security, namely, that the barons shall choose five-and-twenty barons of the kingdom...who shall be bound with all their might, to observe and hold and cause to be observed...the peace and liberties we have granted...to them by this our present Charter, so that if we...or any one of our officers shall in anything be at fault towards anyone, or shall have broken anyone of the articles of the peace or this security, and the offence be notified to four barons of the afore said five-and-twenty...the said four barons shall repair to us...and petition us to have that transgression redressed without delay. And if we shall not have corrected the transgression...within forty days...the said four barons shall refer the matter to the rest of the aforesaid five-and-twenty barons, and these five-and-twenty barons shall, together with the community of the whole land, distrain and distress us in all possible ways, namely, by seizing our castles, lands, possessions, and in any other way they can, until redress has been obtained as they deem fit.

The sixty-first article of Magna Carta, then, concludes Kern, “incorporated the right of resistance in the written public law of a nation, and the creation of a committee of resistance gave it the vitality necessary for institutional development. Neither ecclesiastical legal doctrines, nor the theory of popular sovereignty, nor the idea of governmental contract have any credit for this achievement.”

So in this discussion, Kern observes how the customary law, formally, and both church and the nobility, practically, constrained the power of the king within the medieval constitution. However, there is a notable lacuna in Kern’s discussion of the legal constraints and pluralist counterbalance to kingly power. We’ve only discussed here the doubtlessly important means by which the high born constrained the king. How though did the commoners act to constrain kingly power? This is where we’ll turn our attention in the next installment of this series on legal pluralism.

So…if you want to be on top of each new installment in this important series on the recovery of legal pluralism, and haven’t yet, please…

And if you know of others who’d interested in joining along in this exploration of roots and nature of legal pluralism, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Though, of course, it would be mistaken to underestimate the contribution of the French to the popularity of this erroneous equation. Though at least they really did overthrow a king. Though again, hardly the tyrannical or absolutist one of French Revolutionary lore. Louis VXI was arguably as much a man of the French Enlightenment as many of the revolutionaries.

Regular readers will have noticed that I rarely name people when I’m criticizing a position. That’s largely because I’m uninterested in getting drawn into interweb drama; readers can decide for themselves on whom the shoe may fit. I want to make a rare exception here, largely because the individual in question has been so kind as to repeatedly recommend my book, The Managerial Class on Trial. That’s Robert Barnes: lawyer and legal analyst extraordinaire. I very much appreciate all the times he has promoted the book, but his dismissal – which I’ve heard of from others and was repeated on a recent Sunday show with Viva Frei – of the final third of the book seems oddly misplaced. I’m told that in the reading group he dismissed the idea that restoration of some kind of “monarchy” (I wasn’t as careful with that term as I’d be now) was simply undertaking a dictator. Oddly, though, that very final third of the book which he has on multiple occasions dismissed, on the basis of the American myth I’m guessing, goes some way in demonstrating the error of equating king with dictator. The millennium of the medieval constitution illustrates that there was nothing about kingship that made it monarchy in the literal sense, certainly not dictatorial. It was the reintroduction of Roman Law that turned kings into monarchs through its legitimization of sovereignty. However, Robert (if I might break the fourth wall), as I show in the earlier part of the MCOT, which you do recommend, that ideology of sovereignty seamlessly passed from the personal sovereignty of the monarch to the impersonal sovereignty of the modern state. The tyranny you worry about is not an inherent product of kingship but rather of Roman Law's sovereign state – which we now live under. You seem to assume that theories like divine right of kings, absolute monarchy, and sovereign immunity were transparently lived facts. The existence of a legal or political theory, though, says nothing about how it manifested in practice. As Nicholas Henshall illustrates in The Myth of Absolutism (discussed back in the main text and the footnote below), too often we act as though because a political philosopher — Bodin, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, etc. — describe a political situation in a certain way that the situation was that way. In the case of absolutism, Henshall demonstrates, such assumptions were not only empirically erroneous, but defied common sense. People (including political philosophers) with an advocative axe to grind are commonly inclined to generate straw men and red herrings in their cause. That’s largely been true of the story of “absolute monarchy” claims, even in the modern era. And this series will demonstrate how even less leash such ideas got under the medieval constitution, prior to the fuller impact of the reintroduction of Roman Law.

Nicholas Henshall, The Myth of Absolutism: Change & Continuity in Early Modern European Monarchy, 1st edition (New York: Routledge, 2014). On the question of absolutism as propaganda, Henshall shows that In fact, pre-Reformation the English used absolutism as a charge against the French in the two countries’ long rivalry. Following the Reformation, absolutism morphed into a charge against Catholic crowns, which maintained the original condemnation of France while allowing the allegation to be leveraged against the English’s own Catholic crowns, such as Mary, and the dubious Stuarts. Post-French Revolution absolutism became a crude condemnation of the ancient regime, making a caricature of the former’s actual pluralism.

Fritz Kern, Kingship and Law in the Middle Ages (Clark, N.J: Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2013).

Though it won’t be highlighted in detail, here, in future installments to this series, there’ll be much more to say about this idea of the customary law.

For anyone interested in exploring this dimension of the feud in more depth, I’d strongly recommend chapters 1 and especially 2 in the impressive work, Otto Brunner, Land and Lordship: Structures of Governance in Medieval Austria, trans. Howard Kaminsky and James Van Horn Melton (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992). Brunner states unambiguously that “the feud was an essential element of the medieval constitutional structure.”