This post is part of a series on the implications of Karl Polanyi’s “great transformation” argument for analysis of Schmitt’s spatial revolution. An index to the series is provided here.

Toward the conclusion of the last installment to this brief series on Polanyi in the spatial revolution, we reviewed the emphasis he put upon the influence of the machine in driving the great transformation. However, from a certain perspective, one could say we haven’t yet addressed what Polanyi saw as the greatest machine of all: the self-regulating market. It was this creation of a market economy that is the central force driving the great transformation. Following out from the logic of it we see all the other effects noted by Polanyi and that clearly fit our characterization of the spatial revolution. The idea of the market became the rationalization for a vast sweep of changes to both the economy and society. And all of that, Polanyi argues, was premised upon the widespread (and in many cases, somewhat self-serving) myth that “man” by nature was a creature intrinsically disposed to barter.

To appreciate how this great transformation of turning a society into an economy occurred, it is necessary to recognize the leveraging of this barter myth. Polanyi goes on to describe how all this was advanced within the intellectual circles of the epigones of the market regime.

No society could, naturally, live for any length of time unless it possessed an economy of some sort; but previously to our time no economy has ever existed that, even in principle, was controlled by markets. In spite of the chorus of academic incantations so persistent in the nineteenth century, gain and profit made on exchange never before played an important part in human economy. Though the institution of the market was fairly common since the later Stone Age, its role was no more than incidental to economic life.

Herbert Spencer, in the second half of the nineteenth century, equated the principle of the division of labor with barter and exchange, and another fifty years later, Ludwig von Mises and Walter Lippmann could repeat this same fallacy.

A host of writers on political economy, social history, political philosophy, and general sociology had followed in [Adam] Smith’s wake and established his paradigm of the bartering savage as an axiom of their respective sciences.

Adam Smith’s suggestions about the economic psychology of early man were as false as Rousseau’s were on the political psychology of the savage.

Division of labor, a phenomenon as old as society, springs from differences inherent in the facts of sex, geography, and individual endowment; and the alleged propensity of man to barter, truck, and exchange is almost entirely apocryphal.

While history and ethnography know of various kinds of economies, most of them comprising the institution of markets, they know of no economy prior to our own, even approximately controlled and regulated by markets.

...the same bias which made Adam Smith’s generation view primeval man as bent on barter and truck induced their successors to disavow all interest in early man, as he was now known not to have indulged in those laudable passions.

...if one conclusion stands out more clearly than another from the recent study of early societies, it is the changelessness of man as a social being. His natural endowments reappear with a remarkable constancy in societies of all times and places; and the necessary preconditions of the survival of human society appear to be immutably the same.

It’s worth mentioning that outside the parameters of the book under examination here, Polanyi did a great deal of research on historical markets.1 He goes on to assert that it’s in the very nature of humans to not privilege material goods, but rather social status:

The outstanding discovery of recent historical and anthropological research is that man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships. He does not act so as to safeguard his individual interest in the possession of material goods; he acts so as to safeguard his social standing, his social claims, his social assets. He values material goods only in so far as they serve this end.

I will say that I don’t think this claim is exactly accurate. Humans, especially males, are evolved to pursue both control over material resources and high social status – though both of these are pursed in the interest of increased mating options and opportunities.2 So, while his use of the term “only” is not really justified in the final sentence, at its core the statement is directionally correct, given our remarkably social nature, and the different interests arising from specific social contexts.

He elaborates on the differences of interests manifested in other historical societies:

These interests will be very different in a small hunting or fishing community from those in a vast despotic society, but in either case the economic system will be run on noneconomic motives.

Reciprocity and redistribution are able to ensure the working of an economic system without the help of written records and elaborate administration only because the organization of the societies in question meets the requirements of such a solution with the help of patterns such as symmetry and centricity.

...an important part of the population [of Trobriand islanders and neighboring groups]...spends a considerable proportion of its time in activities of the Kula trade. We describe it as trade though no profit is involved, either in money or in kind; no goods are hoarded or even possessed permanently; the goods received are enjoyed by giving them away; no higgling and haggling, no truck, barter, or exchange enters; and the whole proceedings are entirely regulated by etiquette and magic. Still, it is trade...

The Bergdama returning from his hunting excursion, the woman coming back from her search for roots, fruit, or leaves are expected to offer the greater part of their spoil for the benefit of the community.3

In contrast then to reading this market-legitimizing allegation of the human propensity to truck, barter, and exchange, in the interest of producing greater economic value, Polanyi offers an alternate explanation, not only for the historically accurate economic dynamics, but also for the activity usually cited to justify the belief in an innate disposition to trade for profit.

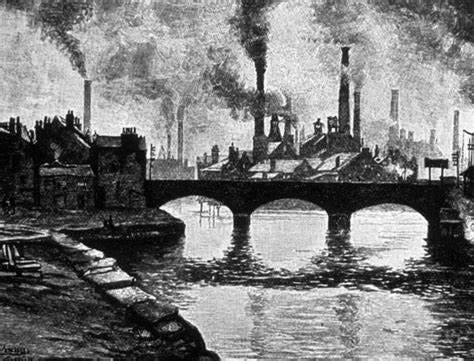

...the gearing of markets into a self-regulating system of tremendous power was not the result of any inherent tendency of markets toward excrescence, but rather the effect of highly artificial stimulants administered to the body social in order to meet a situation which was created by the no less artificial phenomenon of the machine.

The orthodox teaching started from the individual’s propensity to barter; deduced from it the necessity of local markets, as well as of division of labor; and inferred, finally, the necessity of trade, eventually of foreign trade, including even long-distance trade. In the light of our present knowledge we should almost reverse the sequence of the argument: the true starting point is long-distance trade, a result of the geographical location of goods, and of the “division of labor” given by location. Long-distance trade often engenders markets, an institution which involves acts of barter, and, if money is used, of buying and selling, thus, eventually, but by no means necessarily, offering to some individuals an occasion to indulge in their propensity for bargaining and haggling.

...while human communities never seem to have forgone external trade entirely, such trade did not necessarily involve markets. External trade is, originally, more in the nature of adventure, exploration, hunting, piracy, and war than of barter.

Obscure as the beginnings of local markets are, this much can be asserted: that from the start this institution was surrounded by a number of safeguards designed to protect the prevailing economic organization of society from interference on the part of market practices.

This emphasis upon safeguards for the protection of society from the corrosive effects of markets leads Polanyi into a more detailed unpacking of just what was involved in the local markets, and their relationship to their hosting towns.

The most significant result of markets—the birth of towns and urban civilization—was, in effect, the outcome of a paradoxical development. Towns, insofar as they sprang from markets, were not only the protectors of those markets, but also the means of preventing them from expanding into the countryside and thus encroaching on the prevailing economic organization of society. The two meanings of the word “contain” express perhaps best this double function of the towns, in respect to the markets which they both enveloped and prevented from developing.

The typical local market on which housewives depend for some of their needs, and growers of grain or vegetables as well as local craftsmen offer their wares for sale, shows as to its form indifference to time and place. Gatherings of this kind are not only fairly general in primitive societies, but remain almost unchanged right up to the middle of the eighteenth century in the most advanced countries of Western Europe.

Local markets are, essentially, neighborhood markets, and, though important to the life of the community, they nowhere show any sign of reducing the prevailing economic system to their pattern. They are not starting points of internal or national trade.

In fact, he observes:

Internal trade in Western Europe was actually created by the intervention of the state. Right up to the time of the Commercial Revolution what may appear to us as national trade was not national, but municipal.

These shifts in trade vectors, inter-municipal, which is sometimes called international, and the eventual rise of national trade, allowing town and country intercourse, were all the products of specific social and political forces struggling over the strategies for allowing the benefits of trade, while containing their destructive effects. While Polanyi is always concerned with dispelling the myth of natural inevitability, and emphasizing the communal forces of resistance, we can clearly see the grinding march of the spatial revolution in the story he tells.

The Hanse were not German merchants; they were a corporation of trading oligarchs, hailing from a number of North Sea and Baltic towns. Far from “nationalizing” German economic life, the Hanse deliberately cut off the hinterland from trade. The trade of Antwerp or Hamburg, Venice or Lyons, was in no way Dutch or German, Italian or French. London was no exception: it was as little “English” as Luebeck was “German.” The trade map of Europe in this period should rightly show only towns, and leave blank the countryside—it might as well have not existed as far as organized trade was concerned.

Trade was limited to organized townships which carried it on either locally, as neighborhood trade, or as long-distance trade—the two were strictly separated, and neither was allowed to infiltrate into the countryside indiscriminately.

...the burgesses found themselves in an entirely different position in respect to local trade and long-distance trade.

Spices, salted fish, or wine had to be transported from a long distance and were thus the domain of the foreign merchant and his capitalistic wholesale trade methods. This type of trade escaped local regulation and all that could be done was to exclude it as far as possible from the local market. The complete prohibition of retail sale by foreign merchants was designed to achieve this end.

An increasingly strict separation of local trade from export trade was the reaction of urban life to the threat of mobile capital to disintegrate the institutions of the town. The typical medieval town did not try to avoid the danger by bridging the gap between the controllable local market and the vagaries of an uncontrollable long-distance trade, but, on the contrary, met the peril squarely by enforcing with the utmost rigor that policy of exclusion and protection which was the rationale of its existence.

By maintaining the principle of a noncompetitive local trade and an equally noncompetitive long-distance trade carried on from town to town, the burgesses hampered by all means at their disposal the inclusion of the countryside into the compass of trade and the opening up of indiscriminate trade between the towns of the country.

The mercantile system was, in effect, a response to many challenges. Politically, the centralized state was a new creation called forth by the Commercial Revolution which had shifted the center of gravity of the Western world from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic seaboard and thus compelled the backward peoples of larger agrarian countries to organize for commerce and trade.

Polanyi argues that this remarkable story of the expansion of mercantilism, and its constant confrontation with town regulation of markets constituted a major step in the direction of the great transformation. It however was not yet the achievement of that transformation. And in fact he points out that on the basis of the events discussed here, the great transformation could not be yet considered inevitable.

The next stage in mankind’s history brought, as we know, an attempt to set up one big self-regulating market. There was nothing in mercantilism, this distinctive policy of the Western nation-state, to presage such a unique development. The “freeing” of trade performed by mercantilism merely liberated trade from particularism, but at the same time extended the scope of regulation. The economic system was submerged in general social relations; markets were merely an accessory feature of an institutional setting controlled and regulated more than ever by social authority.

Much as Grossi’s analysis pointed us in the direction of the mercantile revolution, including the re-opening of long distance trade routes, as explaining the changing conditions that increasingly pressured medieval jurists to look beyond customary law, for other jurisprudence instruments (i.e., Roman law) to legally cope with the newly emerging conditions; so Polanyi argues that it was this same mercantile revolution that created new challenges for societies that needed to contain the dynamic forces of the markets that arose to cope with these newly emergent needs and locales of trade.

Initially, medieval pluralist society responded to these economic forces with increased regulation, to protect society from the corrosive risks of such markets. However, as we’ve seen above, before very long there were intellectual forces – the market equivalent of Grossi’s legal monist humanists – who aspired to rationalize, promote, and systematize the social invasion of such barter activity: the inexorable reduction of society to economy.

All that paved the way for the next phase of the great transformation: the emergence of the “big self-regulating market” – a mechanism of such rationalist expansionism and universalist individualism that it would rightly be called vanguard of the spatial revolution. Here too we’ll encounter spatialist intellectual apologists and boosters anxious to defend the economization of society, fueled by the marketification of the economy. Though, all that, it will turn out, is another instance of insidious managerial class ventriloquism – the real agent wielding the supposed invisible hand. And all that was built upon the edifice of the radical social transformation entailed in the pervasive commodification of human life.

This is what we turn our attention to in the final installment of our series on Polanyi in the spatial revolution. So, if you want to see that post, hot off the press, and haven’t yet, please…

And, as usual, if you know others who’d enjoy joining us along these journeys of exploration, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Karl Polanyi, Primitive, Archaic, and Modern Economies: Essays of Karl Polanyi, ed. George Dalton, First Edition (Boston, Mass: Beacon Press, 1971).

I’ve elaborated on these points in multiple places, for instance: Michael McConkey, Biological Realism: Foundations and Applications (Vancouver, B.C.: Biological Realist Publications, 2020).

My understanding is that the second part of that claim is not generally true. While I can’t speak for the Bergdama specifically, generally the fruits of female gathering are kept within the family, while there is a greater propensity for band- or tribe-wide sharing of meat – which is usually hunted collectively. While females may gather in groups, this was only for social reasons. Each one would have been able to gather her roots and fruits just as easily alone. The hunting of meat depended upon strategies only made possible by collective action. For much discussion and sources on this topic, see the three books in my trilogy on the social dimensions of human evolutionary biology: Michael McConkey, Not for the Common Good: Evolution and Human Communications (Vancouver, B.C.: Biological Realist Publications, 2016); Michael McConkey, Darwinian Liberalism (Vancouver, B.C.: Biological Realist Publications, 2018); McConkey, Biological Realism: Foundations and Applications.