This post is part of a lengthy series exploring the world of legal pluralism, particularly (though not exclusively) as it was grounded in the world of the medieval constitution. For a full index of the installments so far, see the introductory post, here.

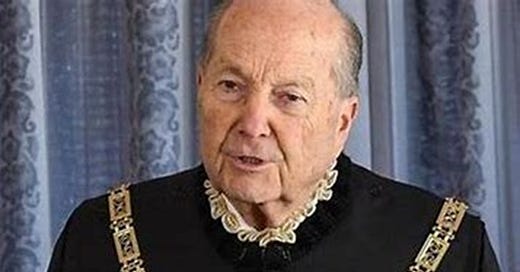

With this installment of our series on the Lessons of Legal Pluralism, I’m starting an extended stretch of posts unpacking the insights from a book by Italian scholar and jurist Paolo Grossi (29 January 1933 – 4 July 2022). He was a multi-time award winning historian of law before having a distinguished career on the bench.

Paolo Grossi is an intriguing legal theorist and historian who, as far as I can tell, sadly only seems to have benefited from the translation into English of but a single one of his many books. Following his prestigious academic career, he was appointed to Italy’s Constitutional Court, which appears to bear a close resemblance to the U.S. Supreme Court, being (as the name might imply) Italy’s highest court on matters of constitutional law. Grossi served on the Constitutional Court for nine years, 2009 to 2018 – the final two years of which he was the court’s President. (I’m going out on a limb and assuming that that title resembles the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.) That one book translated into English is a concise, around 260 page, history of European Law.1

In broad strokes, the story Grossi tells is one of European law going from pluralism to monism and back to pluralism. Though, as would be expected from those of us who recognize that history travels in spirals – not cycles – the pluralism to which we’re returning isn’t exactly the same as that from which we began. Still, there are important points of conjunction between them. Part of that story is also the story of how law emerges from human experience and necessity, only later to be codified as an act of cooptation of the political authority of the law. As he puts it on one occasion:

My reference to experiences of the law is intended to underline an elementary but often ignored truth: the law is written on the hide of people, it is…a dimension of daily life. The law is inscribed in the concrete facts of life before it is written down in statutes, in international treaties and in works of scholarship.

Grossi will start us off in the next installment by situating the medieval constitution, and its proclivity toward legal pluralism, with an analysis of the hard factuality of life, and how under (what I’ve called) harsh Darwinian conditions, law must be reconstituted with greater sensitivity to and in greater compliance with the demands of nature, than had been necessary under the more prosperous conditions of the space biased society of the Roman Empire.

In part 6 of this series on legal pluralism, Grossi reviews material covered previously on this substack and in my new book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, focusing on both the customary, factuality of medieval customary law, and its fundamental contrasts with the eventually dominant Roman Law. Grossi argues that the medieval constitution required a form of law less concerned with formalities and appeals to abstract principles, but rather one rooted in the facts of what did or didn’t work to improve the agricultural production essential to survival amid medieval European life.

In part 7, Grossi turns his attention to the processes that will eventually lead to the shift from the temporalist medieval constitution of legal pluralism to the spatialist legal monism of the political sovereign. He puts his emphasis, in his analysis of that historical shift, upon the changing material and social conditions that legal scholars were required to engage. In the process, he raises some interesting questions about my Nisbetian reading of the motives of those scholars. While, from my perspective, Grossi fails to understand how those conditions came to exist, or what in human biology mediated those material and social conditions, his rooting of Europe’s history of law in those changing conditions goes a large step in the right direction of providing a further scholarly foundation for the phenotype wars model which I’ve been working on, here and in my recent book.

In part 8, Grossi illustrates how it was that the late medieval scholastics, attempting to remain true to the factuality and hardnosed pragmatism of the medieval constitution, nonetheless, confronted with the changing material and social conditions of their world, notably manifest in the rise of expansive mercantilism, attempted the practical mission of supplementing the medieval constitution with apparently beneficial insights of Roman Law. The phenotype wars, though, in broad strokes, always move in but one direction. Once the camel of the spatial revolution got its nose under the temporalist tent wall, the logic of events was set in inexorable motion. Roman Law and its enshrining of centralized sovereignty became ultimately inevitably.

In part 9, Grossi tells the story of the transition from legal pluralism to legal monism, eventually giving rise to centralist sovereignty. And while he acknowledges the vital role played in that process by the renaissance of Roman Law, he also demonstrates that the latter can hardly be blamed entirely for the eclipse of the medieval constitution. For, in broad strokes, the same developments were evident in the history of English law despite the vastly diminished role of Roman Law in that context. As important as the renaissance of Roman Law was, more relevant was the erosion and eclipse of customary law, with its emphasis upon local particularity. On the continent, especially, while the introduction of Roman Law clearly contributed to that erosion and eclipsing, Grossi shows that the European world was experiencing dramatic changes for which local customary law no longer provided effective legal solutions.

In part 10, Grossi charts the movement into a radically abstract legal order in which humanism, building upon its more rigorous assertion of Roman Law, eventually gave form to natural law, with its methodological and possessive individualism. Natural law’s abstract rationalism eclipsed the factuality of the medieval constitution’s legal pluralism. In its place was substituted an abstract axiom of individual equality premised on the equal capacity to own property. In this way, the humanists and the natural law laid the foundations for the emergence, efficacy, and legitimization of the newly rising world of capitalism. Under this new regime, the abstracted individual, shorn of his medieval corporations, intermediary institutions, and customary legal rights, is left naked before the newly ordained political power of the centralized sovereignty.

In part 11, Grossi explores how the triumph of the legal Enlightenment, manifest through the French Revolution, and Napoleon’s aggressive expansion of that revolution, constituted the triumph of legal modernity. And how the triumph of legal modernity constituted the triumph of legal monism. The Enlightenment revolutionaries aspired to grind pluralism of law and institution into historical dust. The spatialist symbiont system – i.e., persons left as abstract, socially naked individuals before the awesome power of a centralized sovereign, imbued with monistic and absolute power – becomes the telltale sign of the triumphant legal modernity.

However, in the final installment on Grossi’s history of European law, we learn that despite the triumph of Enlightenment legal monism, legal pluralism isn’t quite done yet. He describes a backlash against the dominance of legal Enlightenment monism, with its reliance upon possessive, deracinated individualism. As early as the late 19th century, the revival is observable. This revival was a response to a social vacuum left by the extermination of an ancient tradition of customary law.

However, rooting such revival in bureaucratic will rather than hardnosed reicentric factuality displaced organicity with abstraction. Further, combined with the attempt to revive corporatism, practically overnight, the revival wound up being the expression of the administrative state, leaving the effort vulnerable to managerial class ventriloquism and social engineering. In the end, both Italian Fascism and German National Socialism, predictably, embraced the rhetoric of corporatism, while simultaneously gutting any remanent of legal pluralism which might be associated with the shell of medieval corporatism.

Even at that though, as traumatic as fascism was (however unfairly) for the reputation of corporatism, consistent with the methodology applied throughout his book, Grossi leaves us with his assurance that the material and social conditions of our postmodern world presently leave the sustainability of legal monism, with its centralized sovereignty, deeply crippled. While the 20th century revival, predictably, given its crucial vulnerabilities, was a false start, the future of the legal order somehow must lie in a recovery of corporatism and pluralism.

I should mention that I left out of this series several topics, including Grossi’s extensive discussion of canon law. For some, such as Harold Berman, this might well be considered an inexcusable exclusion. But Grossi’s book, considering its brevity in pages, is remarkably dense in its detail. Some stuff just had to miss the cut. That exclusion should not be misunderstood as implying that canon was in any way an unimportant part of the medieval constitution’s legal pluralism. There were just other topics which I thought it more important to emphasize, largely because they’re generally less commonly addressed than a more popular topic like canon law.

Finally, as I’m sure will become evident as we progress through Grossi’s book, I read it as a valuable companion piece to my own book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars. While his analysis lacks the deep personality psychology animating the conflicting phenotypes that drive our history, his book beautifully illustrates the dynamics of those phenotype wars at work across the history of European law.

So, Grossi’s book is doubly important for the project of this substack. Not only does it provide a rich case study of a particular battlefield in the phenotype wars, but that specific battlefield, the trajectory of legal pluralism, is an especially important one for those of us who hope to contribute to a social cushion that might yet soften our landing in the coming conclusive arc of the current spiral of the phenotype wars.

So, if you’d like to be on top of this exciting tour through the thought of Paolo Grossi, but haven’t yet, please…

And, as always, if you know of others who’d be interested in the topics discussed here, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Paolo Grossi, A History of European Law, trans. Laurence Hooper, 1st edition (Chichester, West Sussex, U.K. ; Malden, Mass: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). It probably wouldn’t be unfair to describe the book as an intellectual history, though it would be misleading to describe it as a history of ideas, with the idealist assumptions often implied by that term. Grossi is vigilant in his grounding of this intellectual history of law in the material and social realities of the life confronting those on whose hide the law was written.