In previous posts on the spatial revolution, particularly as related to communication infrastructure, we started with a focus upon pre- and early industrial revolution processes and dynamics. (I emphasized in an earlier post that I’d use the term “communication” to include both the movement of information and of things, see here.) Appropriately enough, we began with Harold Innis’ analysis of the transatlantic fur trade. In this post we will follow up on those developments with an overview of the communication infrastructure arising in the wake of the fully realized industrial revolution.

For this tour of the second half (really more like the third quarter) of the 19th century spatial revolution we’ll take as our tour guide the eminent British historian Eric Hobsbawm. As often will be the case in our exploration of the spatial revolution, we’re here looking to insight and guidance from a self-declared Marxist. I appreciate that some would consider such an approach anathema to legitimate scholarship – and particularly intellectual pursuits ostensibly interested in the prospects for an offsetting of the effects of the spatial revolution through a recalling of the pluralist constitution.

I disagree on both counts. I concede that Marxists have tended to emphasize values and solutions which are themselves just different wrinkles upon the same old space biased society model, driven by the managerial class. Nonetheless, regardless of your opinion of their diagnoses or prescriptions, Marxists have been uniquely focused on the historical dynamics and consequences of the spatial revolution. The fact that they call the object of their study “capitalism,” indifferent to the fact that such economic relationships epitomize the revolution of spatial modernism, is immaterial. Their work has constituted a valuable resource for analyzing the material and cultural impact of the spatial revolution. (A point I’ll flesh out in a forthcoming post.)

In Hobsbawm’s case, we’ll be looking at some of the insights in his book, Age Of Capital 1848-1875, originally published in 1975.1 While his purview is vastly wider than we’ll be considering, he does provide a detailed and thorough discussion of the communication revolution occasioning the industrial revolution, which of course are both just aspects of Schmitt’s wider spatial revolution. His primary emphasis in this is an unpacking of the globalizing of the distant corners of the earth under these economic, technological, and engineering processes.

He starts off pointing to the still, at least comparatively, lack of global connectivity prior to his period of focus (1848-75):

If Libya had been entirely swallowed by some natural cataclysm, what real difference would it have made to anybody, even in the Ottoman Empire of which it was technically a part, and among the Levant traders of various nations?

Even in 1848 large areas of the various continents were marked in white on even the best European maps – notably in Africa, central Asia, the interior of South and parts of North America and Australia, not to mention the almost totally unexplored Arctic and Antarctic.

Though we might add, from a Schmittian perspective: that there even was an enterprise to map the world, giving rise to the continental interior white spots, was itself a manifestation of the spatial revolution and the related aspiration to reach across the globe. In any event, toward the end of the period covered by Hobsbawm, just a few decades later, using the value of trade as his metric, the situation is shown to have profoundly changed:

By 1870 the value of foreign trade for every citizen of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria and Scandinavia was between four and five times what it had been in 1830, for every Dutchman and Belgian about three times as great, and even for every citizen of the United States – a country for which foreign commerce was only of marginal importance – well over double.

During the 1870s an annual quantity of about 88 million tons weight of seaborne merchandise were exchanged between the major nations, as compared with 20 million in 1840.

Let us measure the tightening of the net of economic interchanges between parts of the world remote from each other more precisely. British exports to Turkey and the Middle East rose from 3·5 million pounds in 1848 to a peak of almost 16 million in 1870; to Asia from 7 millions to 41 millions (1875); to Central and South America from 6 millions to 25 millions (1872); to India from around 5 millions to 24 millions (1875); to Australasia from 1·5 millions to almost 20 millions (1875). In other words in, say, thirty-five years, the value of the exchanges between the most industrialized economy and the most remote or backward regions of the world had increased about sixfold.

These remarkable changes in global interconnectivity, manifest in trade volumes, Hobsbawm explains, arose from a variety of forces all leaning into the spatial revolution. But if we look closely, we find the psychological disposition of the spatial phenotype – with his enthusiasm for the transcending of borders, a taste for novelty, and the conquering of the particular – on full display.

Precisely how the continuing process of exploration, which gradually filled the empty spaces on the maps, was linked with the growth of the world market, is a complex question. Some of it was a by-product of foreign policy, some of missionary enthusiasm, some of scientific curiosity and, towards the end of our period, some of journalistic and publishing enterprise.

To explore meant not only to know, but to develop, to bring the unknown and therefore by definition backward and barbarous into the light of civilization and progress; to clothe the immorality of savage nakedness with shirts and trousers, which a beneficent providence manufactured in Bolton and Roubaix, to bring the goods of Birmingham which inevitably dragged civilization in their wake.

And Hobsbawm draws to our attention the obvious underlying structures of all these processes. It wasn’t simply that the globe was somehow closer, space shrinking, but that there was (in keeping with Schmitt’s observations on how the industrial revolution was enmeshed in the spatial revolution) a specific industrial infrastructure – a girdle of iron – binding it together:

The world in 1875 was thus a great deal better known than ever before. Even at the national level, detailed maps (mostly initiated for military purposes) were now available in many of the developed countries: the publication of the pioneer enterprise of this kind, the Ordnance Survey maps of England – but not yet of Scotland and Ireland – was completed in 1862. However, more important than mere knowledge, the most remote parts of the world were now beginning to be linked together by means of communication which had no precedent for regularity, for the capacity to transport vast quantities of goods and numbers of people, and above all, for speed: the railway, the steamship, the telegraph.

Hobsbawm illustrates his point with reference to Jules Verne’s most famous novel, published in 1872, which would have been unthinkable back in the 1840s, where Hobsbawm begins his study. Phileas Fogg’s ambitious mission to travel around the world in 80 days was not merely a manifestation of the new spatial revolutionary mindset, though it was certainly that, but also a practical charting of the very communications infrastructure of the closing spatial grip upon the world. Hobsbawm reviews Fogg’s journey, not only reminding us of the exact methods used to transport himself, but provides a running commentary of the relative recentness of each communication medium’s availability for travel.

After demonstrating that Phileas Fogg’s trip was quite plausibly completely in 80 days in 1872, be observes:

We can hardly suppose a circumnavigation in 1848 to have taken, with anything but the best of fortunes, much less than eleven months, or say four times as long as Phileas Fogg, not counting time spent in port.

The key difference, according to Hobsbawm, contrary to what some might think, was not a revolution in seafaring vessels. Though the opening of the Suez Canal, in 1869, simply made the 80 day schedule possible, the fact is that there had been only marginal improvements in such vessels during the period he is considering. In fact, he observes, sail driven ships were still very competitive with steamships. Rather, what made the difference, by the time Verne was to set Fogg off on his journey was the sudden expansion of the global railway network: “what did not exist in 1848, outside England, was anything like a railway network.”

It is impossible not to share the mood of excitement2, of self-confidence, of pride, which seized those who lived through this heroic age of the engineers, as the railway first linked Channel and Mediterranean, as it became possible to travel by rail to Seville, to Moscow, to Brindisi, as the iron tracks pushed westwards across the North American prairies and mountains and across the Indian sub-continent in the 1860s, up the Nile valley, and into the hinterlands of Latin America in the 1870s.

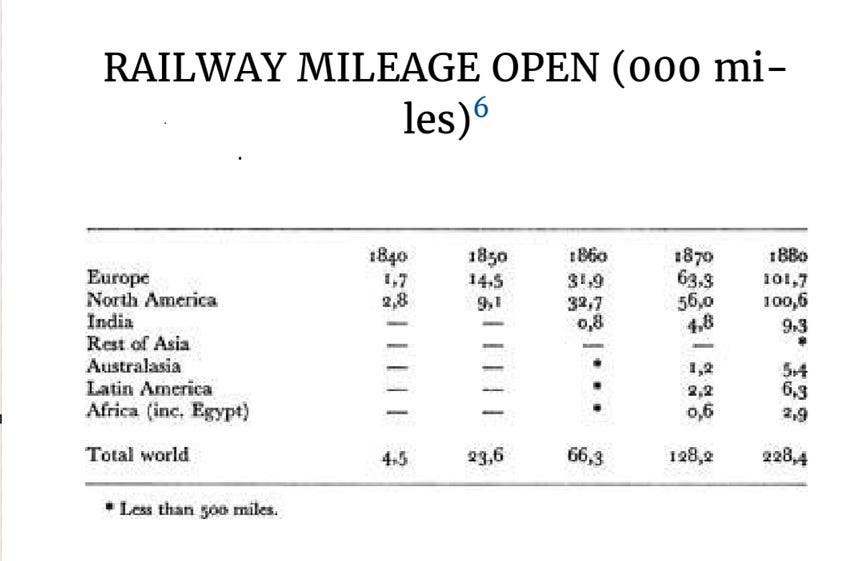

He provides this table to chart the global growth of the railway network:

Though, as essential to this spatial revolution, manifested in industrial capitalism, as was the railway in general, from Hobsbawm’s perspective, to fully appreciate the context of that importance was to see it as the missing communications ingredient, which stretched across great expanses of space to tie together the already well established network of maritime transport.

From the global point of view, the network of trunk railways remained supplementary to that of international shipping.

...the railway, considered economically, was primarily a device for linking some area producing bulky primary goods to a port, whence they could be shipped to the industrial and urban zones of the world.

But even this impressive system of space binding technology, the transport methods of the railway-shipping network, Hobsbawn sees as overshadowed by the miraculous development of the means to transport information.

Rail and shipping, between them, transported goods and men. However in a sense the most startling technological transformation of our period was in the communication of messages through the electric telegraph.

Within a few years [of 1836–7] it was applied on the railways, and, what was more important, plans for submarine lines were considered from 1840, though they did not become practicable until after 1847, when the great Faraday suggested insulating the cables with gutta-percha.

...by the late 1850s a system for sending two thousand words an hour was adopted by the American Telegraph Company...

...this new device, one of the first examples of a technology developed by scientists…could hardly have been developed except on the basis of sophisticated scientific theory.

The familiar telegraph lines and poles multiplied: 2,000 miles in 1849 on the European continent, 15,000 in 1854, 42,000 in 1859, 80,000 in 1864, 111,000 in 1869.

In 1852 less than a quarter of a million [telegraph messages] were sent in all the six continental countries which had by then introduced telegraphy. In 1869 France and Germany sent over 6 million each, Austria over 4 million, Belgium, Italy and Russia over 2 million, even Turkey and Rumania between 600,000 and 700,000 each.

...the actual construction of submarine cables, first pioneered across the Channel in the early 1850s (Dover–Calais 1851, Ramsgate–Ostend 1853), but increasingly over long distances. A north-Atlantic cable was proposed in the mid-1840s, and actually laid in 1857–8, but broke down due to inadequate insulation. The second attempt, with the celebrated Great Eastern – the largest ship in the world – as cable-layer, succeeded in 1865. There followed a burst of international cable-laying which, within five or six years, virtually girdled the globe.

By 1872 it was possible to telegraph from London to Tokyo and to Adelaide. In 1871 the result of the Derby was flashed from London to Calcutta in no more than five minutes...

And, in an insight strikingly reminiscent of Harold Innis, Hobsbawm observes:

[Telegraphs] were indeed of very direct importance to government, not only for military and police purposes, but for administration – as witness the unusually large numbers of telegrams sent in countries such as Russia, Austria and Turkey, whose commercial and private traffic would hardly have accounted for them. (The Austrian traffic consistently exceeded that of north Germany until the early 1860s.) The larger the territory, the more useful was it for the authorities to have a rapid means of communicating with its remoter outposts.

Probably Innis’ most famous acolyte, Marshall McLuhan, had referred to the modern means of communications collapsing the world into something like what he characterized as a “global village.” Hobsbawn too identifies such a process through the globalization of “news.”

Telegraphy transformed news, as Julius Reuter (1816–99) foresaw when he founded his telegraph agency at Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) in 1851.

International news could be cabled freely from a sufficiently large number of places on the globe to reach the next morning’s breakfast-table. Scoops were no longer measured in days, or if from remoter territories in weeks or months, but in hours or even minutes.

...the tightening net of the international economy drew even the geographically very remote areas into direct and not merely literary relations with the rest of the world. What counted was not simply speed – though growing intensity of traffic also brought a powerful demand for rapidity – but the range of repercussion.

Though I won't unpack it here, Hobsbawm provides a lengthy, detailed analysis of the remarkable impact of this globalization of the communication revolution, resulting from the Californian gold rush, examining how those impacts manifested in trade, immigration, and labor rates. Such impacts of course were the result of the very revolutionary global collapse of space which he has been describing. One interesting example of such effects of the California gold rush was the recognition by spatial revolutionaries of the communications importance of the isthmus of Panama, well before the building of the canal, finished in 1914.

The United States government fostered a mail service across the isthmus of Panama, thus making possible the establishment of a regular monthly steamer service from New York to the Caribbean side and from Panama to San Francisco and Oregon. The scheme, essentially started in 1848 for political and imperial purposes, became commercially more than viable with the gold-rush.

...as early as January 1855 the first railway train traversed the isthmus. It had been planned by a French company but, characteristically, built by an American one.

Today we’re all familiar with the global governance aspirations of that faction of the managerial class colloquially called – appropriately enough – the globalists. Using language – to advance propositions – like “the rules-based new international order,” they dream for us a world woven together in such a manner as could only be achieved under the auspices of the fullest realization of Schmitt’s spatial revolution. Though, of course, Schmitt would have been horrified at their schemes. Hobsbawm concludes with an observation that should serve as a reminder to the denizens of the 21st century, not only that such globalist dreams are nothing new, but that their roots are indeed found deep in the history of this spatial revolution, which has girdled the world in steel and cables.

There is no doubt that the bourgeois prophets of the mid-nineteenth century looked forward to a single, more or less standardized, world where all governments would acknowledge the truths of political economy and liberalism carried throughout the globe by impersonal missionaries more powerful than those Christianity or Islam had ever had; a world reshaped in the image of the bourgeoisie, perhaps even one from which, eventually, national differences would disappear. Already the development of communications required novel kinds of international coordinating and standardizing organisms – the International Telegraph Union of 1865, the Universal Postal Union of 1875, the International Meteorological Organization of 1878, all of which still survive. Already it had posed – and for limited purposes solved by means of the International Signals Code of 1871 – the problem of an internationally standardized ‘language’.

Now, a good half century beyond when he first published his book, the present reader with only the slightest effort and reflection likely could list off achievements in the direction of such globalization that might well have dumbfounded Hobsbawn at the time. The globalization, the global homogenization, which seem to be the stamp of the current moment, as Hobsbawn demonstrates, are just the logical extrapolations of a spatial revolution centuries in the making.

And likewise, we have seen that even this remarkable communication revolution under global capitalism has its roots in Innis’ global fur trade and commercial empire, and then even further back in Grossi’s observations upon the transformations brought about in European law as a consequence of the expanding mercantile trade routes of the latter middle ages. As Schmitt would have emphasized, this spatial revolution has been a good half millennium in the making.

I’m guessing for most readers, these last couple posts haven’t been especially unexpected. However much our familiarity with the empirical specifics may vary, most people have some sense that over recent centuries there has been a (or many) communications revolutions(s). And I’d have hoped by now that the present reader would easily identify such communication revolution as a manifestation of an ever more far-reaching spatial revolution.

What I suspect there may be less consensus upon would be an evaluation that that communication revolution, that commercial revolution, and that spatial revolution, has resulted in a historical process which might be accurately described as entailing simultaneously (relative) increasing economic prosperity and cultural embattlement, and possibly even impoverishment. Obviously, how one measures these impacts depends upon one’s own phenotype.

So, with the broad outline of these lines of communication infrastructure in place, we turn our attention in future posts more toward the impacts (which Schmitt, recall, also anticipated) of the spatial revolution upon psychology and culture – and by extension community, identity, tradition, and (as we’ll begin by addressing) time itself. So, if you don’t want to miss that, and haven’t yet, please…

And, if you know of other folks who’d be interested in this exploration of Schmitt’s spatial revolution, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital: 1848-1875, 1st ed. (New York: Vintage, 1996).

Though, generally, Hobsbawn leaves us with no doubt about his stern disapproval of these Randianesque capitalists.