In the last post we looked at troubling tendencies in the modern West toward a degeneracy of federalism into top-down federal states, and ultimately toward national, unitary states. I’ll have more to say about those tendencies in the weeks ahead. However, in that post I also observed that not all the news on federalist tendencies was bad and proposed to look at Switzerland and Canada as alternate storylines in the modern West’s federalist narrative. Upon some deeper digging, I’ve realized that Switzerland is in fact a far more complicated, and interesting, case than I’d initially appreciated. So, what I’ll have to say here on Switzerland is only a very preliminary statement. I’ll return to Swiss federalism in future discussions when it will be more apropos to unpack some of those nuances.

For now, it is interesting to note that, as with the EU, discussed last post, and despite its long history with federalism – going back 700 years – the modern Swiss federation too seems to have been largely modelled upon the U.S. 1787-89 constitutional federation. However, while such an adoption has entailed some of the intrinsic flaws of that model, the Swiss have managed to resist – precisely because of their own distinctive political culture and history of federalism – some of the more serious compromises of federalism experienced by the Americans.

That particular Swiss context is partially explained here by Wolf Linder:

For centuries the Swiss cantons were independent of monarchial rule. Their old regimes were elitist, but they were still very much part of their own community. As small societies, the cantons were not able to develop complex regimes. Most lacked the resources, for instance, to build up bureaucracies, the modern form of “rational power.” Especially in rural regions, public works – such as road-building and the construction of aqueducts in the Alps in the Valais canton – were done on a community basis: every adult man was obliged to work for several days or weeks a year for the common good. In addition, many other economic activities – for example farming in rural regions and crafts in the cities – were bound up in organisations which required collective decision-making. This, and the mutual dependence of people in small societies, promoted communalism.1 2

So, it is interesting that early Swiss federalism was rooted in something very much like what I’ve characterized as the conditions of federal populism. These federal populist conditions were disrupted, of course, by our old nemesis, that battering ram of the left, the French Revolution. Napoleon’s expansion of the French Revolution across the European continent resulted in the imposition upon Switzerland of a unitary government in 1798. While this regime only lasted a few years, it triggered a protracted period of debate and conflict in Switzerland over how it was going to deal with the new world unleased by the French Revolution. Though there were forces that sought to perpetuate a unitary state, deeming it the appropriate response to the rise of larger, threatening national neighbors, the cultural history of the Swiss, rooted in canton life, and the localist liberty such a rooting entailed, rendered such a unitary state direction impossible. Instead, amid the great political upheaval that engulfed Europe in 1848, the Swiss finally settled upon the idea of “modern federalism.”

This 1848 Swiss federal system consists of three levels: federation, cantons, and communes. Much of the functional description of the Swiss model will sound familiar to American ears. The Swiss parliament consists of two chambers: the National Council and the Council of States. The 200 National Council seats are divided among the cantons according to population. The Council of States is composed of equal representation from all cantons: two members from every full canton. The cantons themselves determine the methods for electing their members. Though direct election by the people has now become the rule, historically, many cantons allowed their parliaments to nominate their representatives. All this function and history of the Swiss Council of States of course closely resembles that of the U.S. Senate.

A distinctive difference from the U.S. model is the Swiss use of proportional representation in its National Council elections, which was adopted in 1918. (Only a couple of Cantons use PR for their Council of States representatives.) The expectation was that this proportionality rule would give smaller parties in Switzerland’s segmented party system a better chance. Linder says this objective was achieved only unevenly. In large cantons, such as Zurich, a small party can win one of the 34 seats with less than 3 per cent of the votes. In a small canton, though, with only two seats, a party would need 34 per cent of the votes to win one seat.

What concerns us more, though, is the relative powers enjoyed by the various levels of federated governance. Again, much of it sounds like the U.S. model. Each canton enjoys a certain degree of autonomy, possesses specific legal powers and responsibilities, and has the right to levy their own taxes. They have their own constitutions. While there has been a tendency in recent decades for the federal state to increase its power, the political and cultural history of Switzerland – manifest in the cultural diversity of the Swiss cantons, their political power, and their claims for autonomy – has set narrow limits to central authority. The federal state’s most important powers have been the exercise of foreign relations, the protection of Swiss independence through the maintaining of an army and facilitating peaceful relations among the cantons. The federation was also authorized to conduct a federal postal service and provide common currency and coinage.

There is though an important difference between the Swiss federal model and the U.S. version from which the former has obviously drawn so much. And this is an important distinction for purposes of mitigating the danger of drift toward top-down (masquerading as bottom-up) federalism that was noted in the last post. We can again quote Linder on this point:

In the US, the 10th amendment proved to be a difficult way to shift powers from the states to the central government. Thus, US authorities developed the practice of “implied powers” or the “interstate clause” which allowed the federal government to assume new powers by mere interpretation of the existing constitution. Not so in Switzerland. From the very beginning, the Swiss parliament was reluctant to provide the federation with new powers and has interpreted Article 3 of the constitution in a strict sense. Not only the establishment of a national bank, any form of federal taxes, the creation of a social security system, the construction of federal highways, subsidies to the cantonal universities, and the introduction of environmental policies, but also “small” issues like subsidies for hiking trails all needed formal constitutional amendment and ratification. This is one of the reasons why constitutional amendments in Switzerland are proposed practically in every year while in the US they are rare events.

The proposition to confer any new power on the federation needs not only a majority in both chambers of parliament, but also a majority of the cantons and of the people at a popular vote. As Linder observed, such amendment proposals fail regularly. And the ones that eventually pass often require numerous iterations before they’re deemed acceptable. In contrast to the U.S. model, then, Swiss federalism maintains a powerful feature for putting a brake on centralizing tendencies. This is why controversial policies, such as the introduction of a national pension system, were such arduous endeavors. In the case of Switzerland’s national pension plan, it was originally introduced for vote in 1947. It was only after ten subsequent iterations, in 1995, that the constitutional amendment process described above finally resulted in its adoption.3

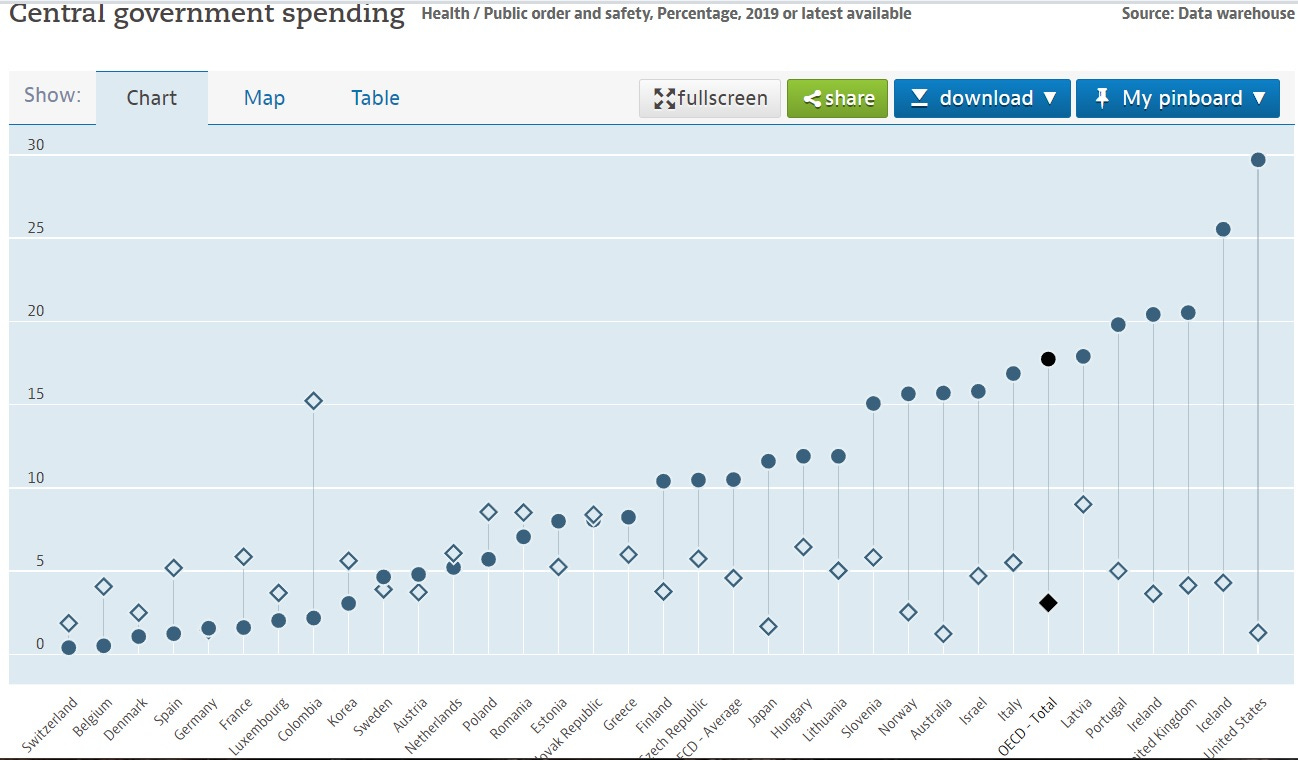

This Swiss brake on centralization of power also explains why central government expenditure constitutes such a small part of the total Swiss public budget, compared to other countries. Compare, for instance, this OECD data4 comparing central government spending on health and public order – with Switzerland and the U.S. at opposite ends of the spectrum.

Recall the point I made in the first post to this substack on federalism: who controls spending, controls the federation. Even if a federation gives lip service to having a genuinely federal, bottom-up nature, if it is the central government that controls the lion’s share of the taxing and spending power, what you really have is a top-down federal state. And, according to the Swiss Federal Department of Finance, the central government’s taxing is not only restricted by the terms of the constitution, but the two most important sources of tax revenue for the central government – direct federal and value added tax – have sunset dates, needing to be periodically renewed through the above identified process, with majority approval by both the people and the cantons.5

So, it may not be surprising then to find out that for the sample year which the Swiss Federal Department of Finance provides (2018), the combined tax revenue of the cantons and the communes exceeded that of the central government: 78 compared to 70 billion Swiss Francs.6 So, tax revenues collected by the Swiss federal government were 47.2% of total collected taxes by governments in Switzerland. In contrast, for the same year in the United States, the federal state collected 64% of the total.7 And I haven’t heard much about U.S. federal taxes having sunset dates, needing periodic renewal by popular referendum and a majority of the states.

So, while I’d certainly say that the Swiss compromised their long history of strong bottom-up federalism by their adoption of the U.S. 1787-89 federal model, unlike either the U.S. or the E.U., Switzerland (perhaps because of that ancient federalist tradition) have proven more successful at mitigating the centripetal tendencies built into the U.S. model. As mentioned off the top, the Swiss context is actually much more interesting than this brief discussion can do justice, especially as it relates to the history, nature, and function of the cantons; again, I’ll have more to say about Switzerland’s federalism in future posts.

For, now, then let’s turn to the still more different case of Canadian federalism. I’m a little challenged around sources, here, so I’ll be doing this mostly by heart. But I think I can manage.8 Though, I’ll be cannibalizing a bit a couple earlier posts about the Canadian constitutional situation (see here and here).9

Unlike Switzerland, taking the bones of its federalism from the US, the Canadian founders aspired to take theirs from Britain. Indeed, the second line of Canada’s founding document, the British North America Act, says that the four founding provinces are to be united “with a Constitution similar in Principle to that of the United Kingdom.” Part of the complication in this choice was that the United Kingdom did not have a strong tradition of federalism – even though it was clear from the start that creating a political state across the northern half of North America would have to be done on some kind of federal basis.

Part of the reason for this choice was that the Canadian federation terms were being negotiated in the 1860s, precisely as the US was embroiled in its “Civil War.” And the Canadian founding fathers believed it was the excessively decentralized nature of the US federal constitution which gave rise to those embattled conditions. It was determined by Canada’s founding fathers that while a purely unitary government didn’t make sense across such a large land mass, federation along the lines of the (then) relatively decentralized U.S. system was to be avoided given its evident propensity to degenerate into intra-federation war. As a result, they established a system that was more federal in name than in fact.

In the new Dominion of Canada (which they originally wanted to call the Kingdom of Canada, but the Brits nixed due to protests from the Americans), the power balance therefore leaned way toward the central government. One manifestation of this centralist bias was the federal government having enshrined in the constitution the power to disallow any provincial legislation of which it disapproved. Additionally, and a cause for grievance pretty much from the founding of the country, for over 150 years, repeated efforts to establish a regionally representative senate (as we’ve seen in Switzerland and the US) in the upper house have been refused and frustrated — in some cases explicitly referring to the desire to maintain the demographic voting power of the original Canada: Ontario and Quebec. (For those interested, in one of those earlier posts I’ve fleshed out further this dynamic of the “real” Canada and the largely colonized “provinces”: see the appendix, here).

However, from a federal populist perspective, over time, unlike the US federation, which has been moving in the wrong direction (see here), toward a federal state, across Canadian history federalism has been gradually moving in the right direction. Almost immediately following the 1867 confederation, over the next several decades, a provincial rights movement emerged, calling for the provinces to be treated as equal, rather than junior, partners in confederation. A series of rulings by the British colonial Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, the highest court for Canada at the time, gradually established this more equal partner status for the provinces – ensuring that their sovereignty was respected within their constitutionally designated areas of jurisdiction.

There were two particularly important developments in this regard. The first of these was the transfer of power over natural resources from the federal state to the provinces. Following a Privy Council ruling in (I believe?) 1923 establishing the legal standard, in 1930 the Canadian constitution was amended to formally transfer those powers. The financial resources provided by this control over natural resources have given the provinces considerably more clout in intra-federal negotiations.

Perhaps connected to this shifting balance of power within Canadian federalism, support for the Canadian federal state's power of disallowance has become rendered effectively null. Invoked 112 time by the Feds against provincial law, it’s use has waned considerably over the 20th century. It has only been invoked once since WWII, and at that time was thoroughly repudiated by the sitting Prime Minister. Though this federal state power remains in the Canadian constitution as it was patriated from Britain to Canada, in 1982, it is entirely dead letter law.10

In some important ways, provincial sovereignty in Canadian constitutional and legal developments has continued to expand. Indeed, it’s not unreasonable to say that in some salient areas Canadian provinces enjoy greater autonomy than do US states, despite the rather opposite places from which each began. For instance, two hotly contested topics in the area of US states’ rights are the rights to nullification and secession. I appreciate that both sides on this debate are convinced they’re correct – what else is new? And I have no interest in disputing the claims of either side. The point is here simply that there clearly are two sides. Some insist the founding document clearly allow states these options, others insist the contrary. Whatever each side thinks, the matter is undeniably disputed.

In Canada, on the other hand, provinces clearly have these rights. Under Section 33 of the 1982 patriated constitution, neither the federal state nor the courts can impose upon a province a requirement to provincial action. This is not a full spectrum nullification power, but refers exclusively to “rights” guaranteed under the Charter. In an earlier post I’ve demonstrated how such “rights” have been weaponized to advance the agenda of managerial liberalism (see here). Though, it hardly should be a foreign concept to regular readers of this substack that such “rights” are always used by managerial liberalism to advance its social engineering agenda. So, this is an important and valuable power of nullification of the federal state’s bureaucratic paternalism and social engineering. Such nullification has a five year sunset clause, but can be renewed indefinitely.

The most famous (in some circles, notorious) use of Section 33 has been by Quebec to protect its unique (in the North American context) French language and culture. Managerial liberals (and indeed liberals of all sorts) complain about the lack of full language rights for the admittedly historic English language community in the province. And, having lived in Quebec for most of the 80s, I appreciate the difficulties it created for that community. However, no sincere federalist or communitarian populist can object to Quebec taking the steps it deems necessary to protect and preserve its communal institutions and traditions. That would be the whole point of federal populism. And it was precisely the constitutionalizing of provincial nullification powers within Canadian federalism which has made this increased provincial autonomy possible. Likewise, it was Quebec which gave rise to that other development in the provinces’ increased federal autonomy.

Due to the failure of Quebec to vote for independence by just the thinnest sliver, in a 1995 referendum, a submission to the supreme court resulted in a ruling to the effect that, while it would not be legal for Quebec to secede unilaterally, in the event of a “strong majority” vote for secession the federal government would be obliged to negotiate the terms of secession. In response, in 2000, the Canadian federal government passed the Clarity Act, which methodically laid out the path for any province to achieve such independence. While there is still some ambiguity (what is a “strong” majority?), disagreement about the fairness of the process, and the reasonableness of the standards, the constitutional path for provinces to secede from Canada is now clearly established as a matter of legal fact.

In this series of legal and constitutional developments, then – from 1930, through 1982, to 2000 – the autonomy of the provinces has grown under the auspices of Canadian federalism. While Canadian federalism began, back in 1867, as something of a fraud or mirage, remarkably against the triumphalist centralizing currents of 20th century history and politics, gradually Canada has been edging toward a considerably more federalist polity. The full range of those federal powers has yet to be tested. And the focus of such likelihood seems in recent years to have shifted from Quebec to Alberta. Time will tell how all this plays out, but the long trend lines have been encouraging.

So, the discussion last post of how federalism has been consistently compromised in the United States should not cause excessive pessimism for those who are hopeful for federal populism to facilitate the revitalization of organic community, sheltering it from the corrosive forces of managerial class social engineering, and leftist French Enlightenment values more broadly. As both the Swiss and Canadian examples show, while the momentum since the 19th century has been increasingly in the direction of centralization and centralized social engineering, such momentum has not been ubiquitous nor irresistible. And, indeed, even in the United States, particularly in response to the COVID hysteria – though not exclusively – there has been an increasing awareness of the need to recover the founding’s deep federalist roots.

For the next couple posts, I want to engage in another of those exercises with which readers of this substack are now familiar: resuscitating an older, perhaps for many forgotten or neglected, thinker who has much to teach us about some of the history and dynamics entailed in these questions of communitarian populism and federalism. So, if you haven’t yet…

And, if you know anyone else who’d be interested in these topics, please do…

Wolf Linder, Swiss Democracy: Possible Solutions to Conflict in Multicultural Societies, 3rd edition (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010). I drew heavily upon Linder’s book for this post, though in the future I’ll have some critical observations to offer regarding his approach to the topic.

It’s striking how much this bit of Swiss history corresponds to the arguments I made in the first post on federal populism, in response to the hypothesized objection that a federal populist model does not protect organic community from the corrosive progressivism, universalism, and rationalism of the managerial class and its administrative state. It appears the Swiss history of federalism does indeed indicate that scale does provide such a defense (see here).

Monika Bütler, “Milestones in the History of the Swiss Pension System: A Politico-Economic Analysis,” Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics (SJES) 135 (January 1, 1999): 369–85.

“General Government - Central Government Spending - OECD Data,” OECD, accessed February 25, 2023, http://data.oecd.org/gga/central-government-spending.htm.

Federal Department of Finance FDF, “Swiss Tax System,” accessed February 25, 2023, https://www.efd.admin.ch/efd/en/home/steuern/steuern-national/das-schweizer-steuersystem.html.

Federal Department of Finance.

“What Is the Breakdown of Revenues among Federal, State, and Local Governments?,” Tax Policy Center, accessed February 25, 2023, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-breakdown-revenues-among-federal-state-and-local-governments.

For some reason, I guess just the relative smallness of the Canadian population, even standard and classic texts on Canadian history and constitutional law are not readily available in electronic form in the usual places. And, spending the winter in Mexico, I didn’t bring my paperback library with me. I brought too much junk as it is. So, again, much of this will be by memory.

Sources drawn from there and elsewhere relevant to this discussion include: Barry Cooper, It’s the Regime, Stupid!: A Report from the Cowboy West on Why Stephen Harper Matters (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2009); David J. Bercuson and Barry Cooper, Deconfederation: Canada Without Quebec (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2002); F. L. Morton and Rainer Knopff, The Charter Revolution and the Court Party, First Edition (Peterborough, Ont: University of Toronto Press, 2000); Peter H. Russell, Constitutional Odyssey: Can Canadians Become a Sovereign People?, Third Edition, 3rd ed. edition (Toronto ; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2004).

On these matters, see: Andrew Heard, “Constitutional Conventions and Written Constitutions: The Rule of Law Implications in Canada,” Dublin University Law Journal 38 (2015): 331; and Russell, Constitutional Odyssey. This history explains why the suggestion that the social engineering, managerial class has maneuvered to surreptitiously sneak “disallowance in disguise,” through the clandestine, extra-parliamentary governance ploy discussed in an earlier post (see here), back into the new post-Charter constitution, is considered so egregious and controversial an allegation.

I'm loving this series. Can't wait to see where it goes!