LEGIBILITY AND THE SPATIAL REVOLUTION

ON SCOTT’S HIGH-MODERNISM

I emphasized in A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars that while it would be a grave analytical mistake to conflate the managerial class with spatialism more broadly, neither should that caution mislead one into failing to appreciate the great extent to which the managerial class has been the driving force and cutting edge of political spatialism. And indeed managerial liberalism’s commitment to bureaucratic paternalism and social engineering – as I hope would be obvious to regular readers by now – is the logical expression of the spatial revolution within the modern world. Just as that revolution conquered exogenous, open space across global territory, so with time, as frontiers shrink, the endogenous expansion of that revolution into the spaces of culture and psychology have logically followed. Indeed, as we saw with Schmitt’s discussion of the spatial mind (see here) such manifestations were always part of the spatial revolution’s logic.

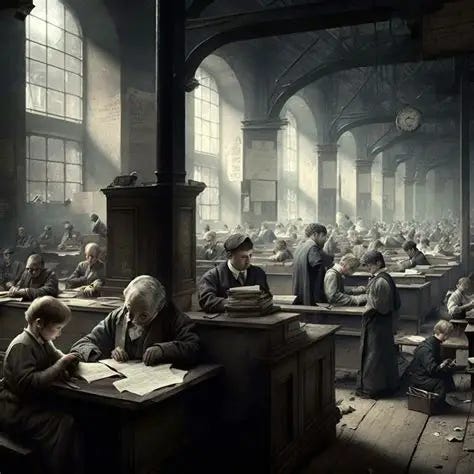

A valuable segue from discussion of the broader penetration of culture, family, and city, into the deeper subjective space of the self will be a reminder of the history of the managerial class’s general commitment to the ordering of open space into the categories of its bureaucratic management. Toward this end we’ll recall the fascinating analysis of “high-modernism” by James Scott.

If the managerial class is defined by its mastery of symbolic thinking (as I argued in The Managerial Class on Trial) and humans are evolutionarily characterized by their evolved capacity for symbolic communication (as I argued in Not for the Common Good: Evolution and Human Communications) then the managerial class, with its specific skills and class-based values and interests, should be expected to appear across human history. Once any society develops written communication techniques and administrative governance functions – i.e., the more it manifests a spatial revolution – the more that the stage is set for the managerial class to play a role in that society.

For instance, going right back to what is usually considered the dawn of human civilization, in Sumer it was the priestly class that exercised control of education, including the teaching of the earliest human writing forms, and likewise administered the extensive public works programs that created the canal and irrigation systems which set the groundwork for the emergence of Mesopotamia as (what is commonly called) the cradle of human civilization. This was already the nascent managerial class taking shape. Unsurprisingly, for those who know that class’s more recent history, across the various Sumerian city states, the priestly class had an uneasy relationship with the various kings and councils of elders: seeming to work with them, but also at times clearly conflicts of interests emerged – entirely predictable from within a materialist class analysis.

These kinds of insights open the imagination to the idea of writing a comprehensive history of the managerial class. Though he did not1 conceive his own project in such a way, there is I believe a case to be made that this is a major part of what James Scott provides in his book Seeing Like a State.2 Scott’s book helps us see the historical role of the managerial class across many centuries, but simultaneously obscures that view by using the vague abstraction of the state as his denominator. Being a self-styled anarchist, this is an understandable focus on his part, but as he himself notes, it’s not as though every state behaves in the manner that he is analyzing in the book.

My case is that certain kinds of states, driven by utopian plans and an authoritarian disregard for the values, desires, and objections of their subjects, are indeed a mortal threat to human well-being.

So, what distinguishes these “certain kinds” of states? Well, the proof is in the pudding. The behaviors he is identifying are preeminently those of the symbolic manipulators: those whose capacity for abstraction allows them to imagine a management, and indeed engineering, of society that displaces possible futures along lines of correlated characteristics and statistical probabilities. Entailed in such a social imagining are the structures and practices that facilitate such administration and engineering. As such, Scott analyzes the centralization, hierarchization, and homogenization characteristic of the footprint of managerial class logic. The organization of space and identity is examined, from monoculture forests to cities and their neighborhoods, from standardize weights and measures to population censuses.

Scott’s analysis points to what he calls a high-modernism, which is concerned with making society “legible” to those who govern it. This legibility, ability to “read” the social facts on the ground, requires engineering to produce a more transparent and so more practically administrable social material.

Consider some passages from the book for a sense of what he is getting at:

...high-modernist ideology…is best conceived as a strong, one might even say muscle-bound, version of the self-confidence about scientific and technical progress, the expansion of production, the growing satisfaction of human needs, the mastery of nature (including human nature), and, above all, the rational design of social order commensurate with the scientific understanding of natural laws. It originated, of course, in the West, as a by-product of unprecedented progress in science and industry.

High modernism must not be confused with scientific practice. It was fundamentally, as the term “ideology” implies, a faith that borrowed, as it were, the legitimacy of science and technology.

...the legibility of a society provides the capacity for large-scale social engineering, high-modernist ideology provides the desire, the authoritarian state provides the determination to act on that desire, and an incapacitated civil society provides the leveled social terrain on which to build.

Early in his book, Scott starts off with a discussion of the socially engineered introduction of standardized, abstract weights and measures, focusing on how they rendered social and economic practice more legible, while simultaneously politicizing such quantifying practices.

Such measurement practices [initially] are irreducibly local, inasmuch as regional differences in, say, the type of rice eaten or the preferred way of cooking chicken will give different results.

Modern abstract measures of land by surface area—so many hectares or acres—are singularly uninformative figures to a family that proposes to make its living from these acres. Telling a farmer only that he is leasing twenty acres of land is about as helpful as telling a scholar that he has bought six kilograms of books.

Without comparable units of measurement, it was difficult if not impossible to monitor markets, to compare regional prices for basic commodities, or to regulate food supplies effectively.

No effective central monitoring or controlled comparisons were possible without standard, fixed units of measurement.

Every act of measurement was an act marked by the play of power relations. To understand measurement practices in early modern Europe…one must relate them to the contending interests of the major estates: aristocrats, clergy, merchants, artisans, and serfs.

And, resonating with our own recent discussions on this Substack, Scott makes the same kind of points about the politics of legibility, centralization of knowledge and control, in relation to many of the grand urban renewal projects of the last few centuries, beginning with the granddaddy of them all, Haussmann’s restructuring of Paris under Louis Napoleon III.

Historically, the relative illegibility to outsiders of some urban neighborhoods (or of their rural analogues, such as hills, marshes, and forests) has provided a vital margin of political safety from control by outside elites. A simple way of determining whether this margin exists is to ask if an outsider would have needed a local guide (a native tracker) in order to find her way successfully. If the answer is yes, then the community or terrain in question enjoys at least a small measure of insulation from outside intrusion. Coupled with patterns of local solidarity, this insulation has proven politically valuable in such disparate contexts as eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century urban riots over bread prices in Europe, the Front de Liberation Nationale’s tenacious resistance to the French in the Casbah of Algiers, and the politics of the bazaar that helped to bring down the Shah of Iran. Illegibility, then, has been and remains a reliable resource for political autonomy.

The logic behind the reconstruction of Paris bears a resemblance to the logic behind the transformation of old-growth forests into scientific forests designed for unitary fiscal management. There was the same emphasis on simplification, legibility, straight lines, central management, and a synoptic grasp of the ensemble.

At the center of Louis Napoleon’s and Haussmann’s plans for Paris lay the military security of the state. The redesigned city was, above all, to be made safe against popular insurrections.

Within Paris itself, there were such revolutionary foyers as the Marais and especially the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, both of which had been determined centers of resistance to Louis Napoleon’s coup d’état.

The military control of these insurrectionary spaces—spaces that had not yet been well mapped—was integral to Haussmann’s plan.

A series of new avenues between the inner boulevards and the customs wall was designed to facilitate movement between the barracks on the outskirts of the city and the subversive districts.

Though he lacks either Innis’s or Schmitt’s sophisticated theorization of space, in the above passages Scott does seem to at least intuitively appreciate that this legibility process of high-modernism entails the conception, penetration, and occupation of “open” space, and in the process the displacing of existing ordered space. It is this “new ordering” of a space that makes it legible for the contemporary managerial class. Scott goes on to make these same kinds of points about many other such grand schemes of this high-modernism, over multiple centuries: emphasizing the engineering for legibility dimensions, the displacement of local knowledge and practices in place of centralized knowledge and control, and the constant politicization, contestations and resistance, from competing class interests.

The problem, though, as noted above, is that he almost entirely neglects the role of class (and phenotype) in these processes, making it difficult to be analytically precise about the competing values and interests which generate the contestations and resistance which he obviously relishes. Again, it is an obfuscation of the real, material dynamics at play that blurs all this into some vague notion of the state.

Interestingly, Scott inadvertently draws attention to the real dynamics behind the obfuscation of his own fixation on the state, right from the beginning. This is how he starts Part One of the book (take special note of the final line):

Would it not be a great satisfaction to the king to know at a designated moment every year the number of his subjects, in total and by region, with all the resources, wealth & poverty of each place; [the number] of his nobility and ecclesiastics of all kinds, of men of the robe, of Catholics and of those of the other religion, all separated according to the place of their residence? … [Would it not be] a useful and necessary pleasure for him to be able, in his own office, to review in an hour’s time the present and past condition of a great realm of which he is the head, and be able himself to know with certitude in what consists his grandeur, his wealth, and his strengths?

—Marquis de Vauban, proposing an annual census to Louis XIV in 1686

For those of us so long steeped in the logic of managerial class rule, it does indeed seem obvious the benefits of such an annual census for maintaining Scott’s legibility, enabling the most thorough and complete governance. It is interesting, in Scott’s own wording here though, that such an idea apparently wasn’t self-evident to the Sun King. Instead, it had to be proposed to him. He had to be sold on the merits of such a legibility project. And who was selling him on this idea? Who is Marquis de Vauban? Our good friends as Wikipedia describe him thus:

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, Seigneur de Vauban, later Marquis de Vauban (1 May 1633 – 30 March 1707), commonly referred to as Vauban (French: [vobɑ̃]), was a French military engineer who worked under Louis XIV. He is generally considered the greatest engineer of his time, and one of the most important in Western military history.

Though originally born to the nobility, during the 1650-53 Fronde, he was arrested and decided to take up the cause of Louis XIV. With a solid professional training at Carmelite College, where he studied mathematics, geometry, and science, this preeminent engineer of his time was managerial class stock right to the bone. And of course, following Schmitt’s own timeline, already by the mid-17th century we were well on the path of our current iteration of the spatial revolution.

For, remember, the point of revisiting Scott was not to relocate our focus upon the managerial class, but rather to emphasize the ways in which that avant-garde aspect of the spatial revolution manifested that revolution’s endogenous-turn to penetration and reconception of the (open) space of city, family, and self. It was the spatialist disposition to administer spaces through the breaking down of conventional and traditional norms, rules, and boundaries, the displacing of ordered space, which is finally manifested in managerialism’s conquering of culture and psychology. And this same managerial penetration – imposition of legibility and hegemony – of the subjective spaces of the self is the ultimate expression of the spatial revolution.

And it’s to that final frontier of the spatial revolution that we turn next. So, if you want to see that discussion, hot off the presses, but haven’t yet, please…

And if you know someone who’d appreciate what we get up to hereabouts, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Sadly, Scott passed away last summer, July 19, 2024.

James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed, Revised ed. edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999).