PLUS ÇA CHANGE...FRENCH CORPORATISM

PART ELEVEN: GUILDS, OLD AND NEW

This post is an installment in a longer series on Guilds, Old and New. To review a full index of all the installments to this series, see the introductory, part one of the series, here.

As I’ve noted on prior occasions, the production of these series has a certain “seat of the pants” dimension to them. As they organically develop, I often find myself mid-stream rethinking an earlier plan. Along such lines, I’d initially planned to give Matthew Elbow’s book, French Corporative Theory1, as much space as I was to give to Ralph Bowen’s book on German corporatist thought. However, for multiple reasons, I’ve now decided against that plan. Not that Elbow’s isn’t a good book, and anyone interested in the intellectual history of French corporatism would be well advised to read it. Among its benefits was to introduce me to some fascinating French thinkers of whom I’d previously not been aware. I found the contributions of Frédéric Le Play (see here) and René de la Tour du Pin (forthcoming) especially interesting in this regard.

Rather, this choice to reduce discussion of Elbow’s book is partially a function of the series now looking larger than I intended. Plus, frankly I don’t find his book quite as useful for a history of guilds. Like the Black and Bowen books, Elbow’s too is an intellectual history, but unlike those books, there’s less discussion of the actual efforts of corporatists and guilds in practice. Though, like Bowen, Elbow was more concerned with the manifestations of corporatism within modernity – the long medieval history of guild corporatism is taken more as a backdrop to the central story.

So, I’ve chosen instead to restrict my discussion of this book to the current post. Herein, I’ll provide a broad stroke overview of the some of the intellectual highlights – though I’ll address these perhaps in greater detail in the next post, based on a French corporatist writer’s own work – but I’ll focus mostly on the one rather modest modern effort at French corporatist practice, under the Vichy regime during WWII. As well as the somewhat surprising follow up to those efforts by what at first blush would seem an unlikely source.

Despite Marshall Phillippe Pétain being an enthusiastic defender of corporatism most of his life, the Vichy project proved to be a failure. While it would seem tempting, given Vichy’s notorious reputation as a puppet of the German National Socialists, to assume the problems of corporatism under Vichy were just the natural expression of National Socialist imposition upon the French government, Elbow concludes that the failure of French corporatism was more complicated than that easy assumption suggests. So, while this post will be a bit on the long side, even by recent standards, it will expedite our movement along in the series.

Elbow begins with a flowery assessment of the promise of corporatism as seen through the eyes of its most enthusiastic French proponents:

Class strife, depressions, and insecurity would be phantoms of the past. All this would be accomplished without scrapping private enterprise, without reverting to an outmoded regime of laissez-faire, and without succumbing to socialism or other forms of statism. The state indeed would cease to be an oppressive leviathan, for much of its action in the economic sphere would be delegated to corporations. In turn, corporations would give counsel to the state on whatever economic-social legislation was necessary, and in this way the economic interests of the nation would secure a direct or indirect voice in the government.

Elbow acknowledges that while modern French corporatism did not enjoy a cohesive theory until well later than in Germany, it would be mistaken to entirely dismiss its somewhat earlier origins. We’ll let Elbow expand a bit.

..while French corporative theory attained its greatest significance during this century, it would be incorrect to assume that it was a full-blown creation of the present.

Although the term " corporative" was not employed in France until after 1870 and there was no cohesive body of French corporative thought before that time, certain political, social, and economic ideas espoused by various theorists later found their way into corporative doctrines.

As would be anticipated by this point in our series, much of the history of French corporatism entailed responses to the French Revolution.

The guilds of the Old Regime were swept away in the destruction of the remnants of feudalism that accompanied the French Revolution. Their demise was made final by the law of March 2, 1791. Immediately vigorous protests arose from members of various trades and professions.

[The law’s] immediate effect was to cause artisans and workers in certain industries to form assemblies for the purpose of extorting higher wages from employers. This in turn resulted in the Chapelier Law of June 14, 1791 which deprived artisans of the liberty of association.

Typical of the petitions to the government during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods was that of three hundred wine merchants in 1806, requesting the reestablishment of the former guilds in general, and their own guild in particular. Governed by a council of six members meeting bi-weekly, the guild of wine merchants would forbid the sale of diluted wine or any substitutes, and would conduct trimonthly inspections to seek out fraudulent practices. Under this plan, four years service and a registration fee of a thousand Kvres would be required for mastership. Masters would be limited to the possession of one shop and participation in the wine business only. The report of the Parisian Chamber of Commerce written by U. Vital Roux indicted all such attempts to interfere with free competition and the proposal of the wine merchants was unsuccessful.

Regnault de Saint-Jean d'Angély, member of the Legislative Body, in a report presented on the tenth germinal year XI made known his longing for the stability which the former guilds gave to work, and deplored the abuses brought about by unlimited trade. Decrying the unfair competition, the perversion of rules of apprenticeship, and the frauds of his day, he explained several proposed remedies such as the “establishment of guilds and the creation of a national label of guarantee.”

...industrial committees of workers and employers set up by Napoleon in 1806 to settle industrial disputes, to dispense justice, and to aid in the administration of labor legislation were thought by guildists to be but a sop to their demands.

Elbow cites another example of such appeal to the benefit of guilds at greater length:

...the petitioners [Levacher-Duplessis’ Mémoire] asserted, " [we] enjoyed a fixed and peaceful status in which we were able to raise our families honorably and to leave to our children after several years of work a modest fortune..." The guild system was "favorable to public morality, to decent customs, to confidence, to the sentiments of patriotism, and to the family spirit whose maintenance and conservation is so important because it is the source of the finest social virtues." Among its other merits, it encouraged perfect workmanship and good quality, essential to the preservation of the foreign market, and it cared for the honest merchant and artisan, victim of misfortune, as well as for the orphan, the widow, the indigent, the infirm, and the old. Worthy guild members could rise to distinction, not only in the guild, but also in the community and state, and by virtue of their position in the guild, were often called to exercise municipal functions. Furthermore, guilds helped to maintain a limited monarchy.

The Mémoire concluded by pleading that France restore the guilds. She should renounce systems which isolated men and hardened their hearts. Instead, she should unite those whom occupations and interests brought together and should allow them to direct and defend their common welfare. As a result "you will soon see the cold calculation of egotism replaced by sentiments of public spirit and the noble results which it alone can produce."

Elbow notes a number of influential French corporatist-style thinkers who early defended pluralism, and the guilds specifically. For example he quotes Jean Bodin, arguably the father of sovereigntist theory, that "just and limited sovereigns are maintained by the médiocrité of the guilds and [other] well-regulated communities." Bodin observed that it was the tyrant who tried to abolish guilds, knowing that the "union of his subjects among themselves is his ruin."

Elbow also emphasized the contribution of what are often called the Utopian socialists, though as we’ve seen (A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars) this Marxian epithet obscured the fact that these were largely right-wing socialists. Among those he mentions are Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and of course Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. The latter has received much attention in our examination of the legacy of Robert Nisbet. (For the more refined version, see A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars; or the first draft in the series on this substack, starting here.) But let’s allow Elbow his opportunity to examine Proudhon.

His conservative outlook was reflected in his devotion to the institution of the family, his championship of the middle class, and his support of inheritance of property. On the other hand, his opposition to interest, to stock exchanges, and to centralized government seem to range him against the status quo. In spite of, and even because of, his contradictions, Proudhon left an indelible impress upon French corporative theory.

Proudhon seemed to gaze almost wistfully back at the guilds of the Old Regime. He claimed his opponents did not see that before '89 the worker existed...in the guild as the wife, child, and domestic in the family; that then, in effect, the working class did not exist in opposition to the entrepreneur class... But since '89 the network of guilds has been shattered without equalizing the fortunes and conditions between workers and masters, without doing or providing anything for the distribution of capital, the organization of industry, and the rights of workers.

Proudhon's whole plan of a people's bank, issuing exchange notes based on commodities and charging no interest, was the result of his fight against "interest," "finance," "capitalism," "stock exchanges," and "Jewish bankers."

Many corporatists also agreed with Proudhon's endorsement of mutual credit and insurance societies, and other autonomous economic associations.

Of prime importance to the development of corporative thought was Proudhon's support of federalism, decentralization and a "cluster of sovereignties"…

Though I won’t dwell upon it at great length here, Elbow does point to a real problem in French corporatism with the common tendency to attempt to marry corporatism with liberalism. This of course was a quixotic effort as I hope should by now be clear. Notwithstanding the notable efforts of Jacob Levy, pluralism and liberalism don’t really mesh (see here). Nevertheless, such meshing according to Elbow was frequently attempted – or at least proposed – over the intellectual history of French corporatism.

During the period of the July Monarchy, a group of social reformers, building upon the ideas of partisans of medieval guilds, Utopian Socialists, and Proudhon, evolved principles and projects which exerted a demonstrable influence on French corporatism.

The new guilds would not possess "privileges and regulations contrary to liberty and to the progress of industry..."

[This iteration of French corporatism] compromised to a greater degree with economic liberalism than the earlier work.

That tendency was overturned in a subsequent school of French corporatism, associated with Albert de Mun and René de la Tour du Pin, but again, that theoretical school will be addressed in the next post. Also, for those interested, Elbow provides discussion of the contributions to corporatist theory of other French Social Catholics, the Syndicalists, Sorel, and Duguit. But as noted above, we’re skipping along to the discussion of corporatism under Pétain’s Vichy administration. Though, a few quotations from Elbow, providing the immediate historical context, would be helpful to keep in mind.

Beginning in 1926, many of the countries of Western Europe adopted regimes that were termed corporatist. In Italy under Mussolini, in Spain under Rivera, Portugal under Salazar, Austria under Dollfuss, the chief industries and occupational groups were constituted by government fiat as corporations, possessing "autonomous" jurisdiction over their own particular industrial spheres. "In practice, however, these 'corporations' either remained vague paper projects to be realized in some distant future," as in Portugal, "or became passive instruments for carrying out the policies dictated from above by an absolute central authority," as in Italy.

As in other European countries, economic and social conditions in France during the interbellum period [1918-1940] constituted a favorable climate for the growth of corporative doctrines and to a limited degree the introduction of practices tending toward corporatism.

So, such notions of corporatism were widely spread through Europe by the time of the Vichy government’s establishment in July, 1940, as unoccupied French territory following the capitulation of France to Germany. In keeping with the model just referenced through Elbow, above, such corporatism was established in a bottom-down manner by the Vichy government. French corporatists of the time opposed this notion of a corporative structure being created by government fiat. Indeed, Elbow acknowledges that Pétain himself, steeped in French corporatist theory, appreciated the arguments against such a hierarchical corporatism structure (see here). Still, as Elbow presents it, Pétain also appreciated the importance of striking while the circumstantial iron was hot.

Pétain was forced to permit reality to modify his theory. Obviously, since a corporative structure had not spontaneously evolved, government measures were necessary to create it. Therefore in the very same speech in which he said that the state should only sanction an already established social order, Pétain announced that it was the state's task "to stimulate social action, to indicate the principles and the direction of this action, and to orient the initiatives." Such a role would be considered too étatiste by many of the French corporatists.

The first important constructive move in the direction of a corporative system was the creation by law of the system of committees of industrial organization.

In the sense that the Pétain industrial committees were an attempt to give the professions themselves a voice in the management of industrial production they were a step in the corporatist direction.

However, as has been seen in this series – and the several series on this Substack, over this past year, exploring the broad strokes of what we might call the pluralist constitution – fascist regimes were always much better at giving lip-service to pluralism, particularism, traditionalism, and corporatism than in providing substantive institutional manifestations of such purported values and cultures. And Elbow observes the same under Vichy:

Nevertheless, in the last analysis, the Vichy government retained supreme control over all phases of production although the committees were often able to influence government decisions.

These industrial committees were established for almost every branch of industrial and commercial activity.

Decisions of any committee were not definitive until approved by the Secretary of State for Industrial Production, who could delegate this right of approval in certain cases, to the government commissioner.

However, with all that acknowledged, it is important to not be too swift in dismissing Pétain’s efforts at realizing French corporatist values. While the regime he leaned into may not have met the heterarchical standards of medievally-informed pluralists or corporatists, unlike say in Germany, such French corporatism should not be reduced to little more than a veil for monist sovereignty. Pétain certainly came closer to realizing the corporatist ideals of both French and German theorists, than for instance had Bismarck. Additionally, not to be slighted was how Pétain’s governance project contributed to the revival and strengthening of the French family and its provincial life. The focus in the present series upon guilds should not cloud our appreciation that these latter loci of temporalist life were at least as important dimensions of a pluralist constitution.

First, Elbow describes what Petain did achieve on the corporatist front:

It was not until the Labor Charter of October, 1941, that labor was placed on a comparatively equal footing with employers in an organization combining the two. This charter was drawn up by the Committee of Professional Organization of the National Council.

The Labor Charter and the various decrees amending it divided French industries and professions into twenty-five "professional families." Each "family" was sub-divided into the following distinct categories: (1) employers; (2) workers; (3) clerks; (4) agents of management; (5) engineers and technicians. Building upon this basic classification of its members each professional family might be organized in one of three ways: by social committees, by mixed groups, or by corporations. While the latter was considered as the most desirable form, it was realized that most "families" would find it easier to begin with the first type.

All the social committees above the level of the factory social committee were to have jurisdiction over the following matters: (1) wages and collective contracts; (2) professional education and apprenticeship, examination, recruiting, and promotion of workers; (3) management of the corporative patrimony and the use of its funds for unemployment, sickness, accident benefits, pensions, family aid, etc.

Strikes and lockouts were prohibited by the charter, and labor disputes were to be arbitrated. Special regional labor courts, composed of two magistrates and three members of the regional social committee were established. A national labor court, composed of three magistrates and four members of the national social committee, was to have final jurisdiction in the arbitration of labor conflicts.

So, again, while Pétain’s achievement would never be confused with the radical heterarchy of Proudhon or the more ambitious Social Catholics, he did achieve more in practical and institutional terms than had anyone else in either the French or German corporatist tradition. Though, to decisively give him the edge on the Third Reich, we need to also factor in his explicit efforts to revive the pluralist family and province.

Like most corporatists, [Pétain] insisted on the importance of the family.

To protect the family Pétain proposed to root out individualism, its arch enemy, and stem the declining birth rate. Among Vichy measures taken to increase the birth rate and improve the family's welfare were an extension of the system of family allowances begun in 1918, the introduction of a family salary among certain classes of workers such as civil servants, and the exemption of large families from inheritance taxes.

Like La Tour du Pin, Charles Maurras, and other corporatists, Pétain was very emphatic in his desire to recreate provincial life, "to revivify the customs and traditions of the petites patries of our incomparable land." A system of regional prefects possessing special police and economic powers was established and plans for a complete provincial organization were studied by a Committee of the National Council. In a letter to this committee, Pétain declared that, while he did not wish to see the départements abolished, he looked forward to the creation of provincial governors and councils.

Communes possessing less than two thousand inhabitants were allowed to elect municipal councils which in turn elected the mayor, but for larger towns the council and mayor were appointed by the prefect. Thus only the small villages were allowed local self-government.

And as Elbow observes, contrary to the misguided judgment of other contemporary commentators and historians, Pétain’s corporatist efforts are not reducible to some pantomime of National Socialist ideology.

Many persons, particularly in America, have held the mistaken notion that the Vichy corporative system was merely a German importation imposed upon the recalcitrant French. Such was not the case. France possessed a long tradition of corporative doctrine and there were many corporatists in France in 1940 who looked hopefully toward the realization of their ideas. Further, as has been pointed out, the doctrines of the Petain regime opposed at many points those of the Third Reich.

The pluralist concepts of the Petain regime, particularly its desire to give a large degree of autonomy to the family, corporations, and regions as institutions which existed prior to the state, were in opposition to the Nazi policy of centralization under which the citizen's entire loyalty to state, party, and leader was demanded.

So, my reading of Elbow leads me to the conclusion that Pétain’s efforts under the Vichy administration likely warrants more attention and appreciation among those interested in the resuscitation of the pluralist constitution than has been perhaps generally acknowledged. Still, for all that, neither should one whitewash its evident shortcomings and failings. Elbow provides his assessment:

To what extent did the Pétain regime satisfy the expectations of French corporatists? In the realm of theory to a considerable degree it did, but in practice it fell far short of their hopes. While it preached anti-étatisme, in reality the strong arm of the Vichy government was omnipresent.

The workers and peasants of France did not respond with enthusiasm to the Vichy corporative system. By December, 1941, only nine of the eighty departmental labor unions had rallied to the Labor Charter. The Catholic syndicalists and twenty-one federations of the supposedly defunct C. G. T. opposed it. The peasants of France were most uncooperative toward the "new order," and they found myriad of ways to break the Vichy regulations. Hoarding and black market operations came to be regarded as virtues.

Shortages of food, of housing, of labor, incessant demands of the Germans, dissatisfaction among the people, disunion within the Vichy government itself—all these constituted a strong alibi for lack of success. And when one realizes the short period during which the new system functioned—from July, 1940 to the end of 1942—one is inclined to soften harsh judgments of this experiment in corporatism.

French irony, such as it is, we can’t close off this story without a nod to one more surprising twist in Elbow’s tale. First, as general summary of the situation, I quote Elbow in observing, despite the origins of 20th century French corporatist theory in ancient regime corporatism, French corporatism as observed above was far too compromised by its efforts to make corporatism rhyme with liberalism. That though, as we’ll see, isn’t the ironic twist.

...corporative ideas were not products of the twentieth century. To no small extent they were built upon various concepts prevalent before 1870. To the Middle Ages and the ancien regime corporatists were indebted for the notion of guilds, the concept of a state limited by groups such as the family, province, and profession, the Thomistic doctrine of just price, and the ideals of good workmanship, paternalism, and Christian fraternity. They adopted certain of the anti-laissez-faire arguments of Levacher-Duplessis and other early nineteenth century partisans of restoration of the guilds. In the works of the Utopian Socialists and Proudhon, they found schemes for class cooperation and mutualism which helped to mold their corporative doctrine. The writings of such social reformers of the July Monarchy as La Farelle, and of Social Catholics of the Second Empire, though somewhat influenced by economic liberalism, suggested guild ideas more in harmony with an industrial order than those of Levacher-Duplessis. The doctrines of political philosophers like Bonald, Chambord, and Comte contributed organismic theories of the state.

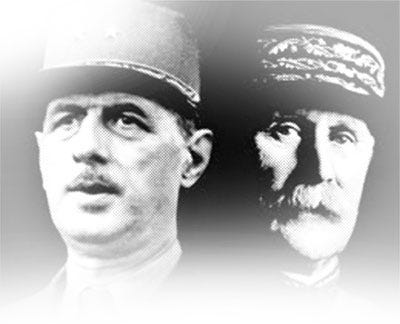

While there may be a certain irony in French corporatist revivalism trying to adopt the very liberal principles, funneling into the very spatial revolution, commericalism, and modular individualism, which gave rise to the aspiration to recover pluralism, the twist to which I referred was more contemporary for Elbow (remembering that his book was published in 1953). Rather he observes that the great nemesis of the Vichy government, none other than Charles de Gaulle had surprisingly endorsed the institutional instruments of his sworn fascist enemies: “In an ironic twist of events, General Charles de Gaulle, arch opponent of the Pétain regime, has declared for corporatism.”2

In a speech to the miners and other workers at St. Etienne on January 4, 1948 he proclaimed:

“We have had enough of the opposition between the different groups of producers that is poisoning and paralyzing French industry. The truth is that the economic recovery of France, and at the same time the advancement of the workers, is bound up with the problem of association, which we shall have to follow.”

The type of association advocated by De Gaulle seemed to be corporative. In any group of industrial enterprises, all those who have a part, including chiefs, officials, clerks, and workers would, under a system of organized arbitration, decide together their conditions of work and principally their remunerations.

“They will set these in such a way that from the employer down to the hand laborer they will receive under the law, scaled according to hierarchy, a remuneration in proportion to the output of the enterprise.”

Likewise De Gaulle advocated political representation of these associations. He stated that "once French activity has been rendered coherent through association, its representatives should be incorporated within the state."

De Gaulle's appeals to family, religion, army, constituted orders of society, and national unity were not too different from those of Pétain. Some have seen in his [combative] and nationalistic Rassemblement populaire français a movement analogous to the French Fascist groups of the interbellum period. In his demand for a strong executive who would balance and integrate in a nationalistic sense the great socio-economic groups of the country, De Gaulle has shown himself to be close to the spirit of French corporatism.

All this incorporation into the state sort of thing does seem doomed to displace heterarchy with hierarchy. But that has been a continuing theme of the story, hasn’t it? What can I tell you: plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

And interestingly, though Elbow leaves off his story of French corporatism in 1953, neither in the hands of de Gaulle, or Gaullism, did the story end there. Just to put a brief bow on all of this I’ll refer to a nice, concise essay by Kay Lawson, bringing the story up into the early 1980s.3 Lawson observes that, in fact, while he was always careful to avoid the use of corporatist rhetoric, and openly dismissed corporatism as incompatible with his self-identified preference for plebiscitarian democracy, the fact of the matter – even if by other names – de Gaulle did repeatedly advance corporatist ideals of what our German theorists would have described as the Ständestaat.

A leading opponent of the Pétain regime and a consummate politician (the latter label one he would of course have scorned), de Gaulle did not use the word "corporatism," perhaps not even to himself. But his pronouncements and his proposals demonstrated a profound affinity for that system of government and that mode of industrial-state relationship.

...de Gaulle had little or no use for independent associations. His plebiscitarian style made him an ardent foe of intermediary organizations of all types, which he characterized as self-seeking and obstructionist. Political parties were, to his mind, the worst offenders, but other groups were almost equally suspect.

However, the Gaullist remedy for the selfish obstructionism of interest groups was much more openly corporatist in nature (although again it must be pointed out that de Gaulle never identified it as such) and much more drastic. When he addressed the question of relations with labor, de Gaulle spoke frequently of "concertation" and urged that workers and employers work together, in associations, to ensure the economic recovery of France. Such composite associations would be an improvement over the wrangling of separate trade unions and managerial groups...

For all his corporatist (even if not by name) enthusiasm, de Gaulle proved incapable of persuading the key parties to move French government in a corporatist direction. That seemed to be the end of the story when de Gaulle, in 1953, withdrew from political life. Those who know their French history, though, will know what Elbow couldn’t have realized with his 1953 book, that de Gaulle would return yet again, as the savior of the nation, amid the Algerian War crisis, in 1958. And in Lawson’s estimation, he came back no less dedicated to his corporatist cause.

Indeed, in the end, de Gaulle staked his political future precisely on the achievement of some form of corporatist state. This latter situation arose out of the crisis of May, 1968, amid a wave of demonstrations and strikes that swamped France, throwing the country into chaos. Initially slow to react to the situation, eventually de Gaulle sought to resolve the crisis through his mechanism of preference, a referendum. And an interesting referendum question it was.

This is not the place to recount the complex history of that dramatic confrontation, but it should be pointed out that de Gaulle's first response, once he could be persuaded to take the situation at all seriously, was to call for a referendum. The referendum had by then become his favorite means of renewing his bonapartistic relationship with the mass of French voters; whatever the ostensible subject, he habitually made his own leadership the real issue of each plebiscite, promising to resign if the vote went against him.

It was customary for each referendum to ask the French voters to give a simple yes or no to a complex question, but de Gaulle outdid himself in 1969. The April referendum had two distinct parts but called for only a single vote. The first part referred to a program of regional decentralization that had long been pending and was widely endorsed; the second asked the French voters to approve a constitutional amendment transforming the French senate into a quasicorporatist assembly. Under these provisions half the senators would continue to be chosen by regional and local politicians but the other half would be chosen by organized socioeconomic groups. Thus reconstituted, the upper house would be permitted to act only on carefully delimited social, economic, and cultural matters.

What we find in fact then is de Gaulle attempting to resolve the French crisis of May 1967 with appeal to a form of Ständestaat which would have made a favorable impression upon the more ambitious Social Catholics – German and French. Alas, from the perspective of the corporatist, this intriguing chapter in the history of European corporatism too came to a disappointing end. The French people – for a variety of reasons upon which Lawson speculates – ultimately voted no to the referendum proposition, and so sent the most iconic French leader of the 20th century off into his final retirement from political life. And with him went his corporatist ambitions.

For those interested, Lawson’s book does explore the continuing pangs of corporatism within Gaullism after de Gaulle over the next decade plus. In the end, though, a rather reserved conclusion is drawn:

On the basis of past experience, the most reasonable prognosis would seem to be that the French fascination with corporatist practices will continue under socialism in the immediate future and receive the renewed enthusiastic support of Gaullism in the more distant future, but that France, determinedly if not cooperatively pluralist, will never carry this fascination to the point of becoming a fully corporatist state.

And that does seem to be a fair prediction of what has come to pass. The constant struggle of France with corporatism seems to be mostly driven by hierarchical assumptions, which see corporatist achievements too often in organizational forms which might well be considered little more than the kind of monist sovereign manipulation that tainted corporatism under the fascist regimes. And, as we’ll see in the next installment to this series, that fatal flaw in French corporatism was evident in the thought of arguably France’s most ambitious corporatist theorist.

As mentioned, even with this highly condensed treatment of Elbow’s book, we’re not quite yet done with French corporatism. In the next installment to this series, I have a closer look at (to my mind) the most intriguing of the French corporatists, René de la Tour du Pin. So, if you don’t want to miss that exciting post, and haven’t yet, by all means, please do…

And if you know of any one else who’d enjoy the kind of work we do over here, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Matthew H. Elbow, French Corporative Theory, 1789-1948: A Chapter in the History of Ideas (New York: Columbia University Press, 1953).

Total sidebar for any film nuts in the crowd. Have you see Casablanca? Did you catch that weird bit of writing in which we’re asked to believe that irreproachable letters of transit within Vichy unoccupied French territory are supposedly provided this immense authority on the basis of being signed by General de Gaulle? You get unhindered travel rights through Vichy territory on the authority of the guy working the hardest to overthrow the Vichy government? Love the movie but that was a bit of weirdly ill-formed script writing.

Kay Lawson, “Corporatism in France: The Gaullist Contribution,” in Constitutional Democracy: Essays In Comparative Politics, ed. Fred Eidlin, 1st edition (New York: Routledge, 2019).