In earlier posts (here and here), I’ve teased out some of the rough dimensions of Carl Schmitt’s idea of the spatial revolution, such as will be the central focus of this Substack for a while into the future. However, addressing the question of the spatial revolution in Schmitt benefits from appreciating a larger context in his thinking which might not be entirely obvious with a closely focused analysis – which is indeed what I intend to provide in the future. Furthermore, the specific contours of that context have some interesting things to say about Schmitt’s thinking as it might be related to my larger historical model of the phenotype wars. Therefore, before jumping into the spatial revolution stuff, it seems beneficial to offer some preliminary remarks that frames this larger context, and points us toward a sympathy with Schmitt which may not necessary be immediately self-evident.

Toward that end, I want to review some of the key arguments Schmitt made in his 1939 essay, “The Großraum Order of International Law with a Ban on Intervention for Spatially Foreign Powers.”1 As ever, we have to preface discussion of anything written by Schmitt during the 1930s, even into the early 1940s, with the caveat that many attempt to dismiss his ideas as inevitably tainted beyond redemption by his Nazi proclivities. I’ve addressed elsewhere why I don’t believe Schmitt was ever a true believer of National Socialism, even where he undoubtedly tried to theoretically make the most out of the situation, in an aspiration to steer the Third Reich in a direction which he desired (for instance, see here.) And even though the work addressed here was published three years after Schmitt had been publicly denounced by the SS and striped of all his official government and party positions, only allowed to continue his professorship, there are those who continue to see Nazi apologia at work in the essay.

Undoubtedly, lazy or ideologically motivated readers will read and have read Schmitt's appeal to “Reich” as just more Nazi propaganda from Schmitt. That though is not merely an uncharitable, but an obscurantist, reading of his argument, perhaps (charitably) resulting from ignorance of the term's long and nuanced use in German history and language. In any event, even if he did choose the term to resonate with late 1930s Third Reich policy toward Eastern Europe, only a hardened ideologue would fail to see the fecundity of the broader theoretical point. As we’ll discuss momentarily, Schmitt after all did acknowledge that through the Monroe Doctrine the USA had become the first modern, formal Reich. So we’ll continue in my usual fashion of ignoring the merchants of slur-by-association and see where ideas are fertile and where they’re not on the basis of what insights they provide.

As I’ve addressed in the earlier posts and will explore much more in posts to come, Schmitt perceived a distinctive form of spatial revolution to begin around the 16th century. It’s worth noting that of course such a revolution has to be overthrowing something that preceded it, and we’ll have occasion to return to this matter below. As I’ve also discussed in prior posts (and will again in future ones), that spatial revolution was not merely a geographical, or even just a technological one.

It involved a change in the mind of those experiencing and in certain cases driving the revolution. All that has to be spelled out in the future. However, what was not so evident in the later Land and Sea2, though it eventually becomes a core theoretical pillar in arguably Schmitt’s greatest spatial revolution era work, The Nomos of the Earth3 , in this earlier version of the spatial revolution model (and this article does foreshadow a great deal of what was to come in those books), it turns out that Schmitt thought that this spatial revolution was already coming to an end by the early 19th century.

Regular readers here will appreciate that this is a reading of the facts that I’m not inclined toward. So, if I’m going to make use of Schmitt’s spatial revolution analysis, I need to at least address this apparent – at least ideal, if not empirical – wrapping up of the spatial revolution. To understand what Schmitt is getting at here it is valuable to note a distinction he makes between “open space” and “ordered space.” It isn’t just that the spatial revolution occurs in open space, though it does, but more that the very concept of open space is itself a mental product of the spatial revolution. So, let’s unpack all this a little more systematically.

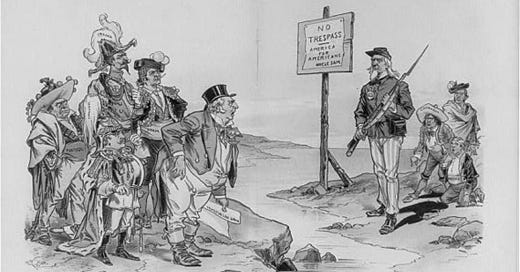

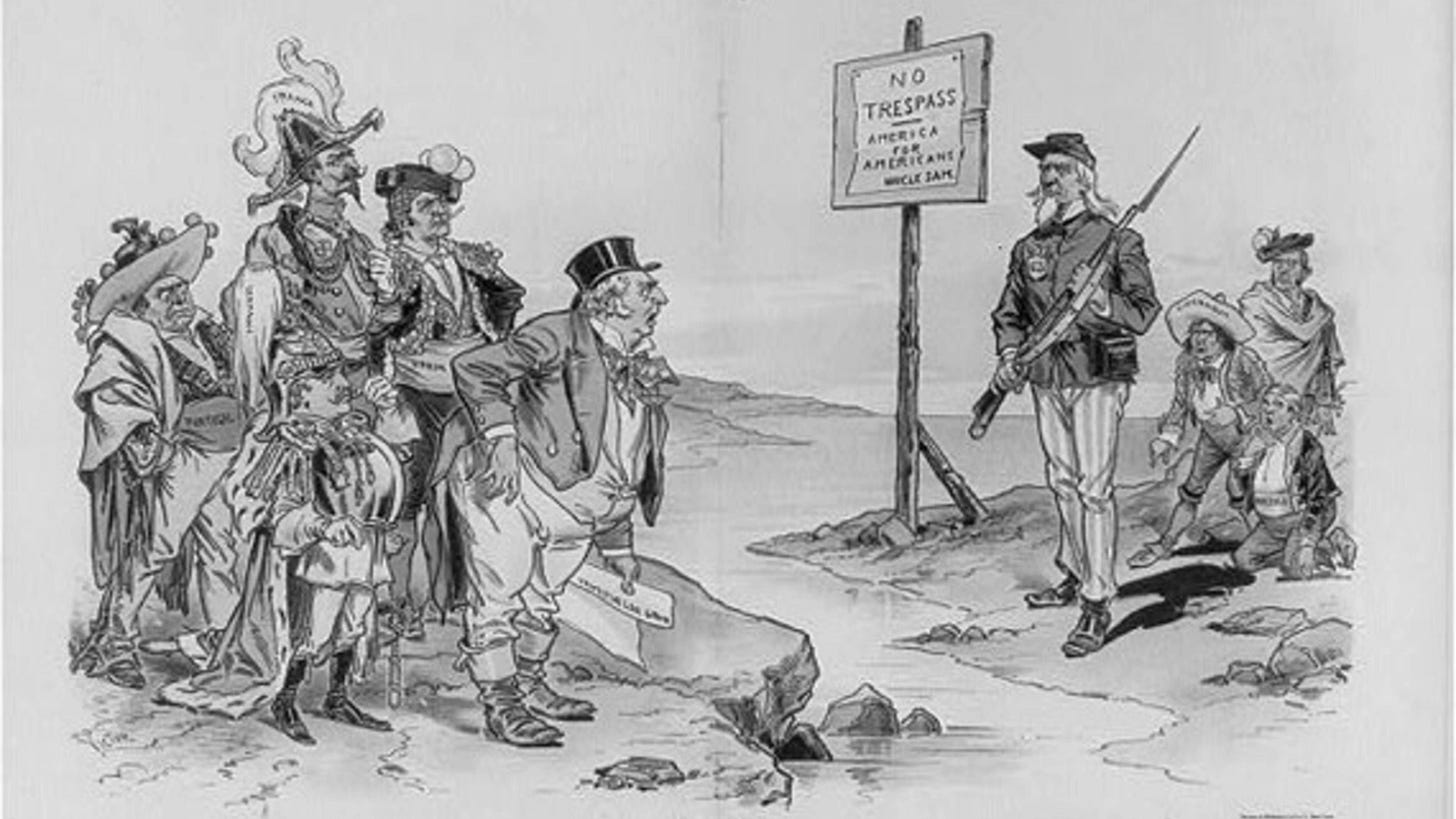

Schmitt is juxtaposing the free, or open, space of a kind of networked vacuum to the ordered space of what he calls a Großraum.4 This is literally translated as a “great space,” but as we’ll see momentarily carries important connotations beyond such an apparently geographic reference. Großraum is the ordered space that stands against the deteriorative universalism of open, free, or vacant space. He illustrates this contrast with the two historical examples of the British Empire and the American Monroe Doctrine. The latter of course was the Doctrine of non-intervention in the American hemisphere by other (re: European) powers proclaimed by President James Monroe during his 1823 State of the Union address. Almost exactly two centuries old at our time, and regardless of quibbles over historical facts of the matter, in Schmitt’s reading the Monroe doctrine had two distinct phases.

Over the course of (almost) it’s first century the doctrine constituted the creation of an ordered, political space, a Großraum which pointed the way toward a new, post spatial revolution world – in at least so far as the latter space was that of vacant universalism. He does concede though that by the doctrine’s second century it began to be increasingly reduced to a veil for U.S. imperialism.5 Still, though, for Schmitt, that initial, earlier phase was an important new precedent in international law, and it seems in my reading of Schmitt, his answer to what Innis might characterize as the destructive and dangerous space bias of the aforementioned spatial revolution. Some passages from Schmitt will be illustrative and emphasize the key points:

The genuine and original Monroe Doctrine had the monarchic-dynastic principle of legitimacy as its counter-doctrine in mind. This gave the status quo of European power division of the time its sanctification and holiness of justice. It elevated the absolute and legitimate monarchy to the standard of the international order and justified on this foundation the interventions of European great powers in Spain and Italy. Logically, it would have had to lead to interventions in the revolutionary processes of state formation in Latin America. At the same time, the leading power of this Holy Alliance, Russia, sought to establish itself with colonies in the far north of the American continent. The peoples of the American continent, however, no longer felt themselves to be the subjects of foreign great powers and no longer wanted to be the objects of foreign colonization. This was “the free and independent position” of which the Monroe Dispatch spoke, of which it was proud, and which it posed in opposition to the “political system” of the European monarchies.

Though it may not be entirely self evident, I do think Schmitt is here reading into his notion of Großraum his earlier famous concept of the political. The Americas, now developing beyond mere colonies of the old world, into sustainable and coherent societies of their own, experience their own identity and sovereignty as being dependent upon relief from that monarchic-dynastic principle, and its implications.

The latter’s ambitions constituted an existential threat to the emergence of the new world societies. There was no doubt that the United States was the central player in staking out such a space, and it clearly acted as the Reich of this American Großraum. In what he calls “the genuine and original” version of the doctrine though this is not a bug or shortcoming, but essential to the very concept of Großraum. This wrinkle is fleshed out further below. For now, though, we want to juxtapose such a Großraum to the spatial universalism of the British Empire.

Again, Schmitt speaks for himself:

Universalistic general concepts that encompass the world are the typical weapons of interventionism in international law.

...the doctrine of the “security of the traffic routes of the British world empire”...is the counter-image of everything that the original Monroe theory was.

The Monroe Doctrine had a coherent space, the American continent, in mind. The British world empire, meanwhile, is no coherent space but rather a political union of littered property scattered across the most distant continents, Europe, America, Asia, Africa, and Australia – a collection that is not spatially coherent.

...the principle of the security of the traffic routes of the British world empire is, seen from the point of view of international law, nothing else than a classic case of the application of the concept of the legitimacy of the mere status quo.

Schmitt observes that under the influence of the spatial revolution, and the regime of the British Empire that rode its coattails, international law has been overtaken by a spatial bias which regards space as geometric dimensions intersected by channels of communication and transportation: “It is more common for the jurist, especially the jurist of international law, of such a world empire, to think in terms of roads and traffic routes than in terms of spaces.”

...the efforts of English international legal policy operated to the effect of making the internationalization and neutralization of the Suez Canal as effected by the 1888 treaty into a prototype for an “international legal system of inter-oceanic canals and maritime routes” for all important maritime routes that were not in English hands.

From Schmitt’s perspective, this is precisely how one should read the famous British doctrine of “freedom of the seas.”

The real context that drives the especially developed interests of a geographically incoherent world empire to universalistic universalizing legal concepts is always evident behind the freedom-oriented, humanitarian, universal interpretation. This cannot be merely explained as cant and deception.

It is an example of the unavoidable link between ways of thinking about international law and a certain kind of political existence.

However, as successful as the British – universalist, open spaces – Empire had been in bringing the Suez Canal under the reign of its spatial regime, that success could not be repeated with the Panama Canal, precisely because of the resistance of the Monroe Doctrine. The network empire of free seas ran up against the brick wall of Großraum. This for Schmitt provided a first indication that the spatial revolution – at least as understood as free, fluid, open, vacant space – was being pushed back against by a new regime of ordered space.

Though I’m reluctant to get into it in great detail, some description of how Schmitt sees the Großraum being ordered needs to be considered. At the core of each Großraum is what, as noted above, he calls a Reich.

A Großraum order belongs to the concept of Reich, which should be introduced into the scholarly discussion as an eminence specific to international law. Reichs in this sense are the leading and bearing powers whose political ideas radiate into a certain Großraum and which fundamentally exclude the interventions of spatially alien powers into this Großraum.

Not every state or every people within the Großraum is in itself a piece of the Reich, just as little as one thinks of declaring Brazil or Argentina a part of the United States with the recognition of the Monroe Doctrine. But to be sure, every Reich has a Großraum into which its political idea radiates and which is not to be confronted with foreign interventions.

The designation “Reichs” that is suggested here best characterizes the facts, in international law, of the connection of Großraum, nation, and political idea that represent our point of departure. The designation “Reich” in no way denies the unique nature of each and every one of these Reichs. It avoids the empty generality that endangers international law, as would be the risk in phrases like “great power sphere,” “block,” “space and power complex,” “common entity,” “commonwealth,” etc., or in the totally meaningless spatial designation “zone.” Reich is concrete and pregnant with respect for the reality of the contemporary global situation.

...as soon as Reichs rather than states are recognized as the bearers of the development of international law and the formation of law, state territory ceases to be the only spatial conception of international law. The state territory then appears as what it in reality is – as only a case of a possible spatial conception of international law – and indeed, a case formerly assigned to the once absolute concept of state, which has since been relativized through the concept of Reich.

...the Reich is not simply an expanded state, just as the Großraum is not an expanded minor space. Nor is the Reich identical with the Großraum, although every Reich has a Großraum. The Reich stands both over the state as characterized through the exclusivity of its spatially characterized state territory as well as over the national soil of an individual nation.

Finally, towards the end of this essay Schmitt, to my mind, lays his cards on the table. What he’s aspiring to here is a revision of international law that in “phenotype wars” nomenclature may be described as a reconstitution of a much more temporal order, pushing against the endless corrosion of community and norms of the spatial revolution. I’ll quote Schmitt at length here as I feel his exposition of these dynamics is an evocative and intriguing exploration of such temporalist restoration precepts.

As soon as the earth has found its secure and just division into Großräume, and as soon as the various Großräume stand before us in their inner and outer order as solid eminencies and forms, other, more eloquent designations will be found for these new things and find acceptance. Until then, however, the word and concept of the Großraum remains an indispensable bridge from the obsolete to the future conceptions of space; from the old to the new concept of space.

The shift in the field of meaning that the word “Großraum” effects as opposed to the word “space” lies above all in the fact that the mathematical-natural scientific and neutral field of meaning hitherto understood by the concept “space” is abandoned. Instead of an empty dimension of area or depth in which corporeal objects move, there appears the connected achievement space belonging to a historically fulfilled and historically appropriate Reich that brings and bears in itself its own space, inner measures, and borders.

The interpretation of space as an empty dimension of area and depth corresponded to the so-called “spatial theory” dominant until now in jurisprudence. This theory indiscriminately interpreted land, soil, territory, and state territory as a “space” of state activity in the sense of an empty space with linear borders.

The theory transforms house and court from a concrete order into a mere entry on the land register’s sheet. It turns the state territory into a mere district of administration or rule, an area of competence, an administrative parish, a sphere of competence, or whatever the various formulations are called.

So we see here a resonance between Schmitt’s ideas of free, neutral space and Innis’ idea that social and mediational space bias is characterized by expansion, administrative as much as military or commercial. Schmitt then provides us a thumbnail sketch of the spatial revolution tied to this “spatial theory” of international law:

The empty, neutral, mathematical-natural scientific conception of space gained acceptance at the beginning of the contemporary political-historical epoch (which is also the contemporary epoch in terms of state and constitutional law) – in other words, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. All the intellectual streams of this era have made their contribution in different ways: Renaissance, Reformation, Humanism, and Baroque; the changes in the planetary picture of the earth and world through the discovery of America and the circumnavigation of the world; the changes in the astronomical picture of the world as well as the great mathematical, mechanistic, and physical discoveries – in a word, everything that Max Weber designated as “Occidental rationalism” and whose legendary era was the seventeenth century. It was here that – to the same degree that the concept of the state became the all-ruling concept for the order of the European continent – the conception of the empty space gained acceptance; an empty space, that is, filled with corporeal objects (and through the objects, sensory perception.) The perceiving subject in this empty space registers the objects of its perception in order to “localize” them. “Movement” occurs before the subject through a change in the subject’s standpoint. This conception of space reached its philosophical highpoint in the aprioriality of Kantian philosophy, where space is an a priori form of knowledge.

In contrast to this spatial theory and the spatial revolution it occasioned, Schmitt conceives the “great spaces” of Großraum as an alternative understanding of space upon which a renewed international law might move beyond empty linear space to a space rooted in concrete community and identity:

...all of today’s efforts towards the over-coming of the “classical” – that is, empty and neutral – concept of space lead us towards a connection fundamental for jurisprudence, one that was very much alive at great points in German legal history, and that the dissolution of law dissolved into a state-referential legal positivism: namely, the connection of concrete order and positioning. Space as such is, of course, not a concrete order. Still, every concrete order and community has specific contents for place and space. In this sense it may be said that every legal institution, that every institution contains its own concepts of space within itself and therefore brings its inner measure and inner border with it.

Schmitt proceeds to illustrate how specific community and identity has throughout German history been entwined with such positive notions of defined, occupied space:

House and court belong in this way to clan and family. The word “peasant” (Bauer) comes, from the perspective of legal history, not from the action of agriculture but rather from construction (Bau), building (Gebäude), just as “dominus” comes from “domus.” “City” (Stadt) means “site” (Stätte). A “Mark” is not a linear border, but rather a spatially determinate border zone. “Property” (Gut) is the upholder of a rule on property (Gutherrschaft), just as the “court” (Hof) is the upholder of court law (Hofrecht). “Country” (Land) is (in distinction from, for example, forest or city or sea) the legal organization of those people building on the country and those ruling the country with their spatially concrete order of peace.

Obviously, these are terms and concepts rooted in German language and history, but if one looks up the etymology of English terms such as borough, village, town, and city, one finds the same kind of appeals to concrete place, identity, and community. And, for Schmitt, a recovery in international law of this notion of space as grounded place, acknowledging the identity of the community that occupies it, was the foundation for such a spatially concrete order of peace.

The concept of the Großraum serves us well to overcome the monopolistic position of an empty concept of state territory and to raise the Reich to the decisive concept of our legal thinking in both the spheres of constitutional and international law. This development is bound up with a renewal of legal thinking, one which may again interpret the old and ancient connection of order and positioning for institutions; a renewal of legal thinking that can restore to the word “peace” its content, to the word “homeland” the character of a species-determining fundamental distinguishing characteristic.

So, even before he wrote his most influential and impressive works on the spatial revolution, Schmitt was already imagining a path out of the legal spatial theory that threatened to dissolve the concrete world of politics, identity, and community into an empty, mathematical-natural scientific and neutral field of meaning: an empty dimension of area or depth. Whether or not one is inclined to dismiss such theorizing as mere ideological rationalization for the Third Reich’s designs upon Eastern Europe, it would be myopic to breezily dismiss the lineation of his position.

Again, in phenotype wars nomenclature, while Schmitt recognized the spatial revolution as the runaway spatialism of an increasingly hyper-space biased society, his theoretical objective here was to leverage the key vector of that revolution into a redefinition of space that snuck in the back door of the spatial revolution a proposed legal proposition that presented a self-limiting projection of such space, thereby containing the revolution’s threatening erosion of the political order. In this way Schmitt was aiming to turn the course of the spatial revolution in the direction of a temporalist renaissance. Space was not to be mere geometric contours, neutrally awaiting occupation by spatialist ambition, but was reconstituted as occupied and inhabited space, in which people lived within their concrete communities.

Insofar as this revision of the juristic concept of space, away from mere expansion and occupation, into one of prior occupation and order, was a deliberate appeal to the pre-revolutionary world of the medieval constitution, Schmitt could certainly be seen here as invoking a temporalist renaissance of rooted, organic, and concrete community order and tradition. This revision of the notion of space becomes the hinge point of his later The Nomos of the Earth, with its appeal to the fundamental role of land appropriation: while the juristic standard of empty space treats land appropriation as a geometric expansion; from the perspective of space as a concrete order, there is always someone else whose land has become the object of such geometric ambitions.6

And so it is perhaps apropos for Schmitt to find the initial political expression of this restoration of concrete space, this assertion of “the political” against mere geometric expansion, in the American invocation of the Monroe Doctrine. For it is in that doctrine, recall, that he sees a staking out of concrete space against the expansionary ambitions of European colonialism.

However, intriguing as all this is – and at least in any explicit sense, of course, this path didn’t materialize in the post-WWII world – Schmitt probably was grasping at straws. And perhaps doing so blindfolded, to boot. His Großraum model may well have constituted a kind of temporalist restoration, but it would hardly have entailed the renaissance of a pluralist constitution, which, as I’ve frequently argued, seems the most plausible means to soften the landing of our hyper-space biased society.

To those familiar with the work, reading this 1939 essay from Schmitt frequently conjures up Alexander Dugin’s theory of a multipolar world.7 An important difference in that regard though was that while Dugin – admittedly, only vaguely and cursorily – did occasionally invoke the idea of some kind of federalism operating within the civilizational poles (i.e., the Großräume) of his imagined multipolar world, Schmitt’s essay exhibited no signs of disposition to such a pluralist constitution. No doubt here we see his persistent commitment to an idea that a people, or nation, be indivisible as an essential condition to its survival in a world of friend-enemy conflicts. We saw in an earlier post (here) Schmitt’s uncompromising attachment to the monist state as the vehicle of such concrete national solidarity, against the supposedly destructive voices of pluralist erosion.8

The great irony in that, of course, is that here, within his newly fashioned Großraum model, the state has been explicitly transcended as the bearer of the obsolete spatial theory of international law. One might have hoped that this reappraisal of the historical role of the monist state might have occasioned not merely a rethinking of the state as spatial revolutionary structure, but also the monism which has always been at the heart of the state as an expression of sovereignty.

However, it doesn’t seem that such rethinking was in the cards; if ever Schmitt was to question his own antipathy to pluralism, this occasion would have provided him a ripe opportunity. Maybe as good an opportunity as he’d ever have.

So, as fascinating as I find this whole Großraum-turn in Schmitt’s thought, and appreciate his recognition of the need to somehow address the cultural solvent of the spatial revolution with some kind of appeal to an increasingly eclipsed time-biased world of political and social order, we can’t expect to find within Schmitt’s thought the necessary tools for rethinking the pluralist constitution as a buffer against hyper-spatialism within the modern world. For all that though, while his prescription may be lacking, I think we will find his diagnosis of the spatial revolution to be a powerful explanation of the central arc in our current spiral of the phenotype wars.

And, it is with such aspirations in mind that, starting in the New Year, this Substack will endeavor to unpack Schmitt’s analysis of the spatial revolution which grew within – and has radiated out from – Europe over the last half millennium. So, if you don’t want to miss that fascinating journey of exegesis, and haven’t yet, please…

Also, any new readers who don’t get this whole “phenotype wars” thing should be reading my most recent book: A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars.

And, of course, if you know of others who’d appreciate what we do over here, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

The English translation I’ll be referring to is dated as 1939-41, as it included later revisions to the original article: Carl Schmitt, “The Großraum Order of International Law with a Ban on Intervention for Spatially Foreign Powers,” in Writings on War, ed. Timothy Nunan, 1st edition (Cambridge, U.K.: Polity, 2015).

Carl Schmitt, Land and Sea: A World-Historical Meditation, ed. Russell A. Berman, trans. Samuel Garrett Zeitlin (Candor, NY: Telos Press Publishing, 2015).

Carl Schmitt, The Nomos of the Earth in the International Law of Jus Publicum Europaeum, trans. G. L. Ulmen (New York: Telos Press Publishing, 2006).

I tend to avoid literal transposing of German words. No doubt there's a perfectly good enough explanation for using upper case for gemeinschaft/gesellschaft, though I resisted in A Plea. And though apparently Grossraum is the phonetically correct rendering in English, it seems the translation kids are insistent upon the literal replication of Großraum/Großräume, for some reason. I'm not sure this makes any sense, as English speakers wouldn't have a clue how to pronounce it, but it looks cool.

It notable that only a handful of years earlier in the decade Schmitt seemed to consider the Monroe Doctrine as an unmitigated exercise in American imperialism, observing that all the political and legal statements of the US have resulted in a situation in which “nobody may demand anything of the United States that is not in accord with the Monroe Doctrine, while the United States may at any time demand respect for the Monroe Doctrine, whereby it is simultaneously recognized that in case of doubt only the United States may determine exactly what the content of the Monroe Doctrine is.” He goes on to observe: “This remarkable elasticity and extensibility, this holding open of all possibilities, this holding open above all of the alternative law or politics is in my opinion typical of every true and great imperialism.” See Carl Schmitt, “Forms of Modern Imperialism in International Law,” in Spatiality, Sovereignty and Carl Schmitt: Geographies of the Nomos, ed. Stephen Legg, 1st edition (New York, N.Y.: Routledge, 2011).

I’d be remiss to not acknowledge that there are those who consider Nomos as, on the contrary, a rationalization of a Eurocentric worldview, presuming to legitimize European colonialism, and neglecting the impact upon those concrete communities of such land appropriations. See, for example, Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Perilous Futures: On Carl Schmitt’s Late Writings (Cornell University Press, 2018). While I certainly understand the grounds for such a claim, even my preliminary, cursory reading of Nomos inclines me to conclude that such a claim is an oversimplification of Schmitt’s argument. But we’ll see, as we progress through Schmitt’s spatial revolution works.

Alexander Dugin, The Theory of a Multipolar World (London: Arktos Media Ltd, 2020), https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/58353014-the-theory-of-a-multipolar-world.

With hindsight, it may seem ironic that the earlier Schmitt, the anti-pluralist Schmitt, was so defensive of the state. Conventionally, this position has been justified during the Weimar era as his effort to create a bulwark against the radical political parties subverting the Constitution. In that light, it might seem strange that he persisted with this commitment to the state in the early National Socialist era. Indeed, Schmitt came in for such condemnation by the SS, eventually removed from the institutions of political life, at least partially due to his inclination to theoretically shelter the state against the "movement." While a superficial view of this tendency may regard it as intellectual consistency, in fact, it strikes me intellectual myopia. The threat in both contexts was precisely the capture of the monist sovereign power of the state. The solution wasn’t to double down on the monist sovereignty of the state, but to defang that sovereignty with appeals to heterarchical pluralism. As we have seen, the National Socialist understood this perfectly and were uncompromising in their institutional attacks upon pluralism – rhetoric notwithstanding (see here and here). It seems that Schmitt’s ideal of the nation made such an appeal to pluralism intellectually impossible.