SOCIAL CATHOLICISM AND THE PHENOTYPE WARS

THOUGHTS ON THE THOUGHTS OF ÉMILE KELLER AND OTHERS

A brief digression from our series on Guilds, Old and New, here. We’re almost into a discussion of guild corporatism among Social Catholics. As part of that research I’ve been reading Christopher Blum’s great collection of writing selections from key French, mostly Catholic corporatists, Critics of the Enlightenment.1 Regular readers here will know that my primary concern with intellectual history is not based in some idealist notion of ideas driving history, the free marketplace of ideas and such poppycock, but rather in such ideas as signal indicators of the prevailing state of phenotypic interests.

Beyond that, there are at times some cross-era correlations of analysis that can be quite interesting. I found a few of these going through the French thinkers in Blum’s collection. Most distinct, at least from the perspective of my own analysis in my book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, was the clear distinction these mostly Catholic thinkers drew between the values and interests of what I’ve called (following Harold Innis) time and space biased society. They criticize the liberals and free marketers for their focus on a delusional national wealth as metric, and obsession with “property rights” — veil behind which the wealthy maintain and entrench their exploitation of the rest of the population.

Bonald’s critique of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations is fascinating, and an obvious example of this type of reasoning. Though perhaps less well known, Frédéric Le Play too makes a comparable argument. Both emphasize that the liberalizing of commerce and industry, with their spatial biases, enforced through the euphemism of national wealth, and weaponizing of private property rights, creates a social ethos which is antithetical to and destructive of the very different values and interests of temporals, and their time biased society. If you’ve read my book, and understand its argument, all this is very clear in the writings of Bonald and Le Play.

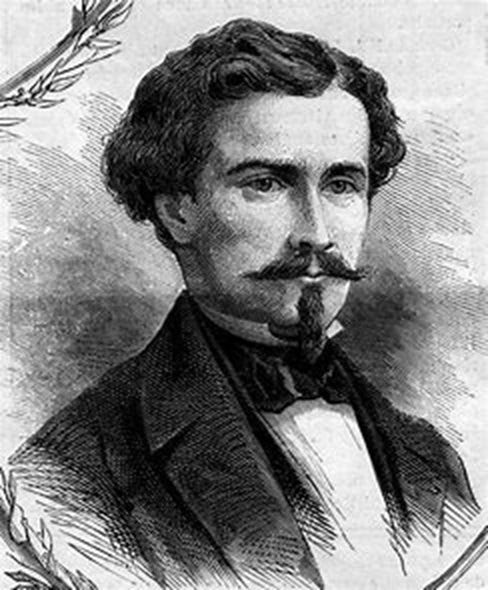

Perhaps even more interesting for me though has been reading Émile Keller. In addition to having the above analysis, consistent with mine in A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, he goes a step further. He emphasizes the function of what I call mass society. That is to say, he provides a bursting of the ideological bubble, claiming that the two left wing (spatialist) positions, of monist sovereignty and private property/free market individualism, rather than being incompatible rivals are actually mutually reliant symbionts. As I’ve emphasized time and again, on this substack, and in my book, the strong, monist sovereign which is necessary to destroy the cultures and traditions that resist individualistic commodification and marketization, is itself fed by the modular individualism which arises from the monist sovereign’s eradication of heterarchical pluralism.

In that light, consider a few intriguing passages from Keller. Take note, these are from a book published in 1865 – two years before Marx’s publication of Capital.

The Revolution created only the unlimited liberty of the property-owner, that is to say the absolutism of those already free, and it could not touch wealth itself without injuring it at its source.

During the Revolution and the First Empire, [the bourgeois] began by gorging himself with the wealth of the clergy, nobility and conquered lands. Then, to save his wealth, he bet on the rising market the day after Waterloo and voted for the fall of Napoleon I.

...he sacrificed liberty just as he had earlier sacrificed glory, our franchise as he had our conquests, in order to protect his privileges. He had been by turns Voltairean, Jacobin, Imperialist, Royalist, Orléanist, Republican, Reactionary.

...when this nefarious band has bought up all the wealth of the clergy and corporations, the lands of the crown and the great families, the concessions of mines and railroads, the present and future wealth of nations, and, as in England, there remains only a minority of property holders amidst a growing multitude of proletarians, who will prevent the angry people, so long incited against the shadow of the Old Regime, from turning against those who have excited, beguiled, and tricked them?

Parenthetically, Keller here is invoking what in Marxist nomenclature is described as primitive accumulation – the dark little secret of liberal capitalism. But, evident among the writers gathered in Blum’s collection, it is clear that the primitive accumulation critique is hardly unique to Marxist critiques of capitalism. The Social Catholics saw the very same process, though their remedy to the problem was of course dramatically different from that of the Marxists. Rather than buying into one end of the mass society closed circuit – i.e., the monist sovereign – they instead worked for the reconstitution of temporalist society, through pluralist institutions of family, church, and guild. The next several installments to the guild series will unpack all this kind of thinking among the Social Catholic activists and theorists of guild pluralism.

But, I haven’t yet gotten to that main point which I wanted to emphasize: Keller’s striking recognition of the symbioses between private property/free market individualism and the powerful monist sovereign – with its distinctive bureaucratic rationality of late spatial revolution (again, see my book to better understand these cursorily acknowledged observations!). Having noted above this long history of primitive accumulation, and the lineage of wealthy elites who finally settled, under prevailing conditions, upon liberal property rights as the most efficacious means to entrench their wealth, Keller goes on to make the following observation:

Then comes – and think deeply on it – the inevitable menace of war and social revolution, the mere specter of which froze the bourgeoisie in terror in 1848. At the end of these violent struggles came the no less lamentable necessity for a new centralization, a new absolutism of the state on the economic terrain.

The liberals pushed for it just like the others. From the moment their privileges were threatened, they found it easy to invoke the arm of the state in deportation and firing squads. At the least scare, they demanded the help of the government. Steal a cabbage from them and they demand that the fields be garrisoned. Incapable of doing anything in their own defense, they require a bureaucrat everywhere. Thus, little by little, everything tends to concentrate itself in the hands of the central power, an abstract being, a mysterious but omnipotent divinity, who will always incarnate itself in one or two men – intelligent, devout, and naturally without excess. The elective or heredity aristocracy will cede place to a new aristocracy of directors, subdirectors, inspectors, and controllers, all well-paid bureaucrats who fulfil their functions with the moderate zeal that one has for other people’s business.

But of course what Keller describes here, in the aftermath of 1848, is an older story, going in France back to 1789 – a point that Keller elsewhere, and the other mentioned Social Catholic writers in Blum’s collection, all acknowledge. The mythology of the existential conflict between monist sovereignty and free market/private property individualism is one that serves both sides – a kind of kabuki theater – in which both sides collude to erase from history the real right wing position, of a pluralist society (see here), rejecting both monist sovereignty and modular individualism. It is interesting to observe 19th century Social Catholic thinkers groping in this very direction.

Similarly neither side of the mass society closed circuit of symbionts wants us thinking about primitive accumulation.2 The fact that such an idea has been wedded to Marxism is the function of a silent conspiracy by both Marxists and liberals. Marxists claim the credit while liberals point to their fellow mass society conspirers in mock accusation. As is seen in reading the Social Catholic thinkers in Blum’s book, though, they were well aware of this process and how it cheated those beneath the economic elite of their patrimony, culture, traditions – their ancient rights and customary law. But since the Social Catholics, like most advocates of a guild renaissance, sought a solution to such historical crimes neither in liberalism or Marxism, but rather in recovery of the corporate pluralism of the medieval constitution, it has been necessary to erase their voices from serious scholarly and public discourse.

The series that this post briefly interrupts, exploring Guilds, Old and New, has aimed to however modestly reverse some of that legacy and help restore the voices of those who advocated for the restoration of guilds, and the corporate pluralism they signify. And that series resumes shortly, so if you want to be on top of new installments as they are posted, but haven’t yet, please…

And, as ever, if you know others who you think would enjoy or profit from our discussions here, please…

And, to reiterate, any newer readers who want to better understand the theoretical background of this post are encouraged to read my book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars.

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

Christopher O. Blum, Critics of the Enlightenment (Providence, Rhode Island: Cluny Media, 2020).

Though I won’t elaborate it here, such primitive accumulation has been noted in the giant wealth transfers which occurred both during the 2008 banking crisis and amid the COVID regime.