This post is part of a lengthy series exploring the world of legal pluralism, particularly (though not exclusively) as it was grounded in the world of the medieval constitution. For a full index of the installments so far, see the introductory post, here.

In the last installment to this series, Grossi discussed the influence of Roman law upon the medieval constitution. In this installment, Roman law’s integration is explored more thoroughly. He also first introduces those he calls the “humanists,” those scholars of the Renaissance who – following my analysis in A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars – might be properly characterized as the vanguard of the spatialist revolution.

As will be seen, reiterating initial impressions from earlier installments, in contrast to Nisbet’s reading of the history, Grossi presents a more nuanced take. The late medieval scholars did introduce Roman law into the medieval constitution; however, their efforts were not a full on spatialist revolution. In fact, their legal project aimed at a pragmatic integration of Roman law into the existing legal pluralism of the medieval constitution. Indeed, to the degree they were attempting to balance the needs of the old, customary law and its brute factuality of agrarian life, with the benefits Roman law provided an emergent mercantile world, trying to balance the virtues of each in light of the challenges of the real world in which they lived, their very effort at marrying Roman to customary law was itself an expression of medieval legal pluralism. As we’ll see, though, eventually, it was the Humanists who upset this balance, pushed all the chips to the center of the table with Roman law and the spatialist revolution. But that’s getting a bit ahead of ourselves.

As usual, I’ll let Grossi lay out his position at length:

…we should note the isolation of medieval jurists. By this rather unexpected term, I mean that our community of scholars does not operate within an all-encompassing political sphere like those that we will examine in the modern period: a political system which governs its subjects and imposes conditions upon them, protecting its lawmakers and conferring authority upon them using a police force and its powers of coercion.

The [medieval] jurists still harboured in their unconscious the naturalistic and factualistic convictions of the pragmatic early Middle Ages, which had settled in the collective imaginary. Late medieval jurists thus studied the facts of their contemporary reality closely and with pleasure, because it was in facts that they might detect the primary quality of their work: effectiveness.

What we have up till now been calling, somewhat vaguely, ‘Roman law’ is in fact a system of laws codified by Justinian in the first half of the sixth century after Christ in the form of the majestic work called the Corpus iuris civilis (‘Body of Civil Law’), made up of the Institutiones (‘Elements’), the Pandecta or Digesta (‘Pandects’ or ‘Digest’), the Codex Justinianus (‘Code of Justinian’) and the Novellae constitutiones (‘Novels’).

…the most precious resource of Roman law, the fifty volumes of Justinian’s Pandecta, which held the treasures of classical legal scholarship, were unknown throughout the early Middle Ages. They were incomprehensible because they were of no use: farmers and shepherds have no need of feathered hats and sequins. Legal historians rightly emphasize the year 1076, when a Tuscan legal document refers to the Pandecta for the first time since antiquity. The return to the Pandecta indicates that it was once again comprehensible: it could be put to use with understanding.

…the cultural inheritance of Rome that seemed to have been lost forever resurfaces with the plenitude of its scholarly detail intact.

The schoolmen wasted no time in grasping this opportunity.

…medieval jurists [though] were careful never to depart from the form of the Roman lex in question, but they often departed from its substance where they found it necessary to do so in their role as constructors of a new legal order.

…their interest in classical culture leant more towards style than substance.

…it is this anachronism that will later lead the humanists to scorn the scholastics as ignorant and asinine, since their interpretations of the classical material were not faithful to its original significance and indeed were often a travesty of it.

Their interpretatio, and I use the Latin term here for clarity, is more of a mediation between ancient law and novel facts than an explanation or exegesis of the source texts.

…their mediation of Justinian’s work was creative: it forged a new law, which typified a historical moment rich in scholarship. We call this law ius commune (literally the ‘common law’, although this is not the same as the English tradition of common law, to be dealt with in the next chapter).

The ius commune was born out of the complex dialogue that these jurists set up between the facts of contemporary life and the rules laid down in the texts of ancient Rome.

Despite the clarity of Roman sources on the indivisibility of dominium (‘ownership’), the late medieval readers of Roman law were also the heirs of the early medieval practices which had shifted the emphasis away from the principle of ownership and towards its effects. Late medieval jurists were conscious of the need to come up with a formal legal justification of the present situation, and so they confidently seized upon certain Roman texts and managed to twist their message so much that they were able to build two different forms of property rights out of the same concept of dominium.

Situations of effective use of goods were now elevated to the rank of dominium utile (‘ownership through use’). This gave rise to the long-lived theory of divisible property, which survived up to the eve of the French Revolution.

So we see clearly in Grossi’s analysis, that the early scholastic jurists, in keeping with the pragmatism of the medieval constitution, set out not to transcend customary law with the introduction of Roman law, but rather to selectively borrow from it so as to bring their legal order in line with the changing nature of their society. In this effort they gave rise to European common law. Though, as Grossi notes, this is not to be confused with English common law – a topic to which I’ll be dedicating an installment later in this series. In this European context, common law refers to this delicately balanced marriage between customary and Roman law.

Of course, from the perspective of the phenotype wars model, those social changes which inspired the scholastic jurists (primarily the growth of mercantilism), addressed as neutral factual occurrence, were themselves manifestations of the spatial revolution – the shift in the arc along the spiral of the phenotype wars leading to spatial hegemony. So, to that degree, the scholastic jurists were indeed facilitating the spatial revolution, even if not as ideologically committed to it as one might have believed from reading Nisbet.

And of course, then, this common law, this allowing of the Roman law in the backdoor as it were, sets in motion changes upon the legal landscape of the medieval constitution, which starts the ball rolling in the direction of the spatial revolution. And that revolution, eventually leads to the enshrining of Roman law as the new standard of legal legitimacy, with its appeal to centralist sovereignty, and assault upon the long tradition of legal pluralism. And as Grossi observes, the very space bias, bias toward expansion, which is the hallmark of space biased society and spatialist hegemony, was already evident in the impact upon the lives of European jurists, once Roman law, under the guise of the common law, had been smuggled into the (we can say, now, former) medieval constitution.

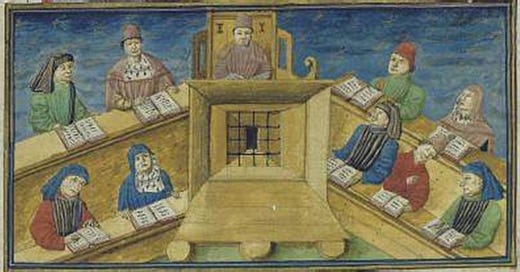

The ius commune was born in the culturally fertile terrain of north-central Italy, specifically in the University of Bologna: the alma mater of legal scholarship. It then spread out across the whole of Europe, uniting it under one legal vocabulary and set of concepts and so allowing any jurist to feel at home wherever his travels across the politically fractured continent took him.

These cultural pilgrims travelled from one university centre to another, and claimed citizenship of a republic of letters to which all mankind might belong. The ius commune set up a universal framework of laws that claimed sole legitimacy through scholarship and effectively unified the legal system of Europe.

However, as significant a role as this common law compromise plays in the spatial revolution against the medieval constitution, it was still a bundle of contradictions, which too often were apparent to contemporary observers. And this situation would be resolved only as the spatial revolution was fully realized with the imposition of the dominance of the Roman law.

…conflict arises because of the simultaneous presence in the same territory and under the same political system of one type of law that is universal and one that is local. The problem becomes more pressing over the course of the thirteenth century, when the first, admittedly timid, efforts at legislation by kings appear, coupled with a lively flourishing of statuti passed by cities, predominantly those of north-central Italy.

So, in this installment, Grossi illustrates how it was that the late medieval scholastics, attempting to remain true to the factuality and hardnosed pragmatism of the medieval constitution, nonetheless, confronted with the changing material and social conditions of their world, notably manifest in the rise of expansive mercantilism, attempted the practical mission of supplementing the medieval constitution with apparently beneficial insights of Roman law. The phenotype wars, though, in broad strokes, always move in but one direction.

Once the spatial revolution camel got its nose under the temporalist tent wall, the logic of events was set in inexorable motion. With the expansion of trade, eventually requiring the expansion of military force to protect trade routes, and the administrative bureaucracy needed to maintain those webs of expansion, the logic of Roman law and its enshrining of centralized sovereignty was ultimately inevitably. And with those historical events came the eclipse of the temporalist golden age of medieval pluralism.

It is precisely this transition, from medieval legal pluralism to legal monist modernity, that Grossi charts for us in the next installment. So, if you don’t want to miss it, and haven’t yet, please…

And if you know of others who’d be interested in this fascinating exploration of legal pluralism, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

>it was still a bundle of contradictions, which too often were apparent to contemporary observers

Does Grossi bring some specific examples of such contradictions? Or do you know of such examples from other sources? That would greatly help understanding.