THE NEGLECTED PERSISTENCE OF LEGAL PLURALISM IN POST-CONQUEST ENGLAND

PART 14: LESSONS OF LEGAL PLURALISM

This post is part of a lengthy series exploring the world of legal pluralism, particularly (though not exclusively) as it was grounded in the world of the medieval constitution. For a full index of the installments so far, see the introductory post, here.

This I expect to be a brief installment to the Lessons of Legal Pluralism series, but one well worth taking some time to parse. It’s a rebuttal to a common story told around the history of English law, along the lines that English law was set upon a whole new footing following William’s conquest after 1066. And this new footing was the institution of legal monism; as we’ve seen, through Grossi’s history of European law, the handmaiden of centralist sovereignty. However, some authors I’ve been reading recently throw considerable doubt upon that interpretation.1 The Normans’ maintenance of the customary law was far more extensive than is widely acknowledged. But that only scratches the surface of what I’ve found so intriguing in this reading.

That intrigue lies in that even the one area in which it is generally accepted that the Normans did introduce legal monism – the centralization of the judiciary, through the use of circuit judges – actually points, not to a thorough legal monism, but rather an impressive persistence of legal pluralism. Understanding this persistence requires appreciating the nature and function of the jury as it took form in post-conquest England.

First, then, quoting Profatt at length, Robert von Moschzisker observes:

“It is the common belief that on his accession to the throne of England the Conquerer made a radical and complete change in the laws and institutions, and that an entirely new system was established on the ruins of the old; but that was by no means the case. While changes and innovations were certainly made, there was no sweeping abolition of laws and customs, no entire uprooting of old institutions, and no extensive interference with the ancient rights and privileges of the people. There were, no doubt, alterations, but they were such only as adapted the old established institutions to the new polity of the Normans. That it was never the intention of William to introduce a new system of laws and customs and abolish the old, is evidenced by his constant endeavors to appear, not so much in the light of one who acquired his rights by conquest, as in the character of one who came to the throne regularly, de jure, as one entitled by his relationship to the Saxon line. It was his constant endeavor to show to the people that the old laws and privileges should remain intact; that their cherished institutions should still remain as before.”

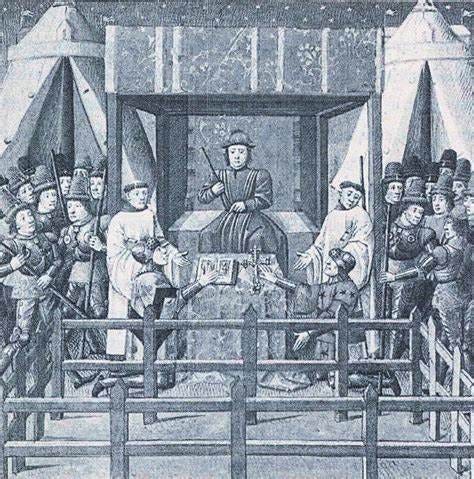

For all that though the Norman conquest did bring one distinctive measure of sovereign centralization. This was the aforementioned centralization of the judiciary through the use of circuit judges, who traveled the country administering the king’s justice.

Alan Harding describes the situation, thus:

…the king assembled a little group of experienced justices to send out from the curia regis to sit in the shire courts of England (rather as the sheriffs went round to sit in the hundred courts). The king’s court moved about ceaselessly with the king, hearing disputes between the magnates at the manors where the king happened to stop…, and it was natural to detach a judge or two from it, as occasion required, or to send a number of groups of justices itinerant (on an iter or journey, or ‘in eyre’) to do similar jobs at the same time in different parts of the country.

And he elaborates in places:

The centre and control of the judicial system was the curia regis, the king’s honour court, and it was feudalism which caused both the great increase in litigation and the centralization of justice.

… it was in the shire court that the itinerant justices sat to take the findings (verdicts, veredicta, ‘true sayings’) of juries representing shire and hundreds and townships.

Fitting the jury into this story runs up against a longstanding dispute within the history of English law over just what was the lineage of the English jury. Moschzisker provides a sense of the debate:

The exact time of the introduction of the jury trial into England is a question much discussed by historians, some of them contending it was developed from laws brought over by William the Conqueror, while others point to certain evidence of its existence, in an embryo state, among the Anglo-Saxons prior to the Norman Conquest; and still others suggest even an earlier date.

And a common alternative explanation is the ancient Scandinavian tribunals. However, Moschzisker also points out characteristics of the latter which are importantly distinct from the English jury tradition:

It will be observed that in all the tribunals of ancient Scandinavia the lay triers, or jurors, performed the double function of judges of both law and fact; the lawman, who presided over them, merely acting in an advisory capacity, to aid in determining relevant questions of law, except where the jury could not agree, when he had greater power.

Furthermore, these tribunals were of a local nature. This constituted an important distinction from the English jury. This unique English circumstance is spelled out here by William Forsyth:

…a distinctive characteristic of the jury system is that it consists of a body of men, quite separate from the law judges, summoned from the community at large, to find the truth of disputed facts in order that the law may be properly applied by the court; that, in considering the ancient tribunals, composed of a certain number of persons chosen from the community, who acted in the capacity of judges as well as jurors, few writers keep this principle steadily in view, and thus confound the jurors with the court.

What then is so important about this distinction? Let’s turn back to Harding for an explanation:

The Anglo-Saxon technique of mobilizing local knowledge certainly continued to be used in courts at all levels…

Juries carrying up local knowledge met the itinerant justices sent down from the king’s court, and so forged the last link in a system of royal justice.

What exactly then was this local knowledge? Certainly, it involved the facts of the alleged offense, and the distinction made between English juries and ancient Scandinavian tribunals is relevant in that regard. But facts themselves are only such as seen through the prism of community standards. The circuit judge may have brought the king’s law to the local community, but nothing more than witnesses was necessary to determine the facts as they related to the king’s law.

Though I’ve yet to find a scholar who said it as plainly as this, it seems to me that a correct reading of these scholars implies that the function of the jury was to legitimize (or not!) the validity of the judge’s ruling, in the name of the king, as being consistent (or not!) with the customary law of the community. The local knowledge of the jury was indeed the link that allowed the king’s justice to be acceptable to all the distinct local communities, with their own customary ways.

From this perspective, the implication of early English juries was an institution for the vetting of any legal theory which would place the action of one of their community members under the king’s law, as expressed by his traveling judge. I wonder too, to what extent the tradition of jury nullification may be traced back to this early English concern that the sovereign’s law not be in – or be perceived to be in – contradiction with local customary law.

I concede that this initial foray probably raises more questions than it answers, but it struck me as a fascinating line of research, which I thought you might find of interest.

We are nearly at the end of this so long series on the lessons of legal pluralism. If you want to see the exciting conclusion of this epic tale, and haven’t yet, please...

And of course, if you know of others who be interested in these topics, please…

Meanwhile: be seeing you!

The authors I’ll be drawing upon here are: Robert von Moschzisker, “Historic Origin of Trial by Jury,” University of Pennslyvania Law Review and American Law Register 70 (1922 1921): 73; William Forsyth, History of Trial by Jury, 2nd ed. edition (Union, N.J: Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2015); Alan Harding, The Law Courts of Medieval England, 1st edition (New York, N.Y: Routledge, 2019).

Very interesting and well written! Yes. Indeed you can have elements of centralization and commonality of law while having large amounts of pluralism and in fact you can have them while still having a very high degree of highly heterogenous decentralization. Proof: The Old Republic of the USA was a highly politically and economically decentralized space (some major areas the economy remained highly so until the 1980s and significantly so until the late 1990s!) with high degrees of variability in economic regulations, fiscal policy, and social policy between states and even towns/cities/counties yet all but one of its states operated within English Common Law (I suppose after a while one should say English Common Law descendent) with only slight variation, and the Federal Government was always there and was never nothing.

Thanks again for the interesting writing, I hope your having a nice weekend.

---Mike