It seems like only last week that people around the world were riveted by the story of the Canadian truckers: their spontaneous movement and its draconian suppression by the Trudeau government.1 In fact, come to think of it, it was last week.

Now almost everyone is obsessed with Russia’s Ukrainian invasion. And I won’t lie, I have opinions on that topic too, but the idea of this blog was never that it should be intellectually blown about by the fickle winds of momentary passions. It certainly is fascinating how the lines of division within the managerial class over the trucker inspired movement radically reconfigured into entirely different divisions over the Ukraine affair. But I’m going to leave that topic aside for now, reserving the option to take it up in the future if I see an opportunity to leverage its lessons for the themes of this substack. I’m not quite ready to leave behind the truckers though.

For those following recent posts, the trucker-inspired movement provided a fascinating test case for the kind of class analysis that informs much of the concern of this substack. And, as at least the first act of this drama concluded last week (whether it’s a one act play or not remains to be seen), there was one final lesson to be drawn from that first act relevant to the themes we address here. The black pilled side of my analysis here is that there are no magical happy endings in political life. The people are never redeemed and granted a world of happiness, safety and prosperity. There’s always a ruling class; they always have their own interests; and given enough time they’ll get nasty about it. The only hope of maintaining some space of freedom lies in a popular movement that provides appropriate and sufficient incentives for either another class (e.g., the bourgeoisie) or more likely a rebel faction of the ruling class (e.g., a surplus elite of the managerial class) to provide the populist insurgency the strategic, logistic and theoretical leadership it needs to throw out the corrupt and/or sclerotic ruling faction of the ruling class. That’s why this substack is called “The circulation of elites.”

However, there’s also a white pill to be drawn from all this too. No matter how powerful the ruling class may seem, regardless of their access to wealth or the means of violence, they always have an Achilles heel: they’re human. And as such they have differing circumstance-derived values and so are always subject to coordination failures. They may be able to agree that they should coordinate, because they want to continue to rule. That though doesn’t mean that practical realities on the ground are going to provide them circumstances that create a dovetailing of interests. Such (eventually) inevitable intra-class conflict of interests is what ensures a monolithic rule of any class is impossible and always leaves open the prospect for the circulation of elites. With that prospect comes the opportunity for populist insurgencies to induce rebel factions of the class to ride them into a new political reconfiguration that opens a previously barred window of possibility for freedom and prosperity – however temporary.

Among the many interesting lessons illustrated by the case study in real-time of the trucker-inspired movement was precisely how this inevitable conflict of interests within the ruling class reveals not only that it isn’t the monolith which some presume, but how those differences in interests can undermine the agenda of the faction that may seem ostensibly to be most in control. To flesh out the context a little, let’s cast our minds way, way back to last week, right around this time. The Trudeau government had introduced the Emergencies Act, which gave it extra-constitutional and extra-judicial powers for dealing with the trucker inspired movement, which was continuing every weekend to make a mockery of the government’s efforts to slander and slur their character and motives. This weekly, three day long, block party (in the frigid Ottawa winter) in support of freedom had to come to an end.

So, Trudeau brought in his Emergencies Act powers and before Parliament even had an opportunity to confirm those powers, he put them into effect, using a massive police show of force to arrest and otherwise clear out the protesters. However, despite the success of the clearing-out operation – at least from a purely technical perspective – and notwithstanding the public condemnation of his draconian measures from around the world, Trudeau informed the country and the world that he wasn’t surrendering his newfound power any time soon. On the contrary, he intended to maintain these Emergencies Act powers for some number of months, yet. And central to this new regime was the declared power to freeze the bank accounts of protest participants or even its financial supporters. Elon Musk compared Trudeau to Hitler; Edward Snowden called these actions tyrannical and obscene. Countries much maligned for their own mistreatment of their citizens, such as China and Iran, mocked Trudeau’s hypocrisy and vacuous posturing on issues of human rights.

None of this dented the armor of Trudeau’s newfound power, nor apparently his resolve in milking it for all it was worth. The country was still in crisis; the truckers could return; trust the government. These were dark days for many Canadians, even many who did not support the truckers were aghast at this blunt expansion of state power. If anything, his regime had double downed with talk of making some of their new powers – particularly the banking ones – permanent. This was moving in a very dark direction.

Then, miraculously, within 48 hours, everything somehow had changed. The crisis actually was over. The situation was under control. The powers were no longer needed. The Emergencies Act was rescinded. And the hundreds of bank accounts frozen as part of the state assault on the populist uprising inspired by the truckers were to be liberated back to their proper owners. And most Canadians were left standing around, saying “what?” Naturally, the blue check marks and other apparatchiks of the managerial class and the administrative state went hard to work rationalizing the decision and even mocking Canadians’ concerns about Trudeau doing precisely what he explicitly said he was going to do just a day, and two days, earlier. None of this instant revisionism though distracted anybody from how remarkable this about face was. What happened?

Trudeau’s astonishing statement came precisely during the deliberations of the Senate on whether to approve the powers. Trudeau, despite his minority government, with the support of the New Democratic Party, handily got the necessary approval from the House of Commons. After the first day of Senate debate, all indication was that he would have the votes there, too. There was some notable pushback on the second day, which has led some to conclude that Trudeau feared losing the Senate vote and so decided it was better to save face and end the Emergencies Act powers. There are a couple of complications with this explanation, though.

First, the role of party partisanship has long been a complicated and touchy issue in relation to the Canadian Senate. While the Senate was intended to be a body of second sober thought, there are enough famous cases of party affiliation carrying the outcome for many people to be concerned how such a vote would play out in such charged circumstances as has been evident over these last several weeks.2 Liberal Party appointees constitute the large majority of the 91 currently sitting senators, with a total of 66 seats.3 And while we’re considering the potential impact on how senators vote, in light of any feelings of loyalty that they may have to those who appointed them, Trudeau has appointed 56 of the senators – a sizeable majority all on its own. So, skepticism about the Senate vote going against Trudeau might be understandable. But the Senate isn’t the House of Commons, and doesn’t involve its strict party discipline, so who knows, maybe the Senate would have voted down the powers. Even if that is true, though, there’s the question of why the Senate would do so. It’s not like any Canadian government institutions have been bold about challenging Trudeau, or the provincial governments, over their alleged extra-constitutional powers during the two years of the pandemic (see here for my reflections on the abysmal role of the courts4).

So, I think we still need some kind of explanation for Trudeau’s utterly remarkable about face on the Emergencies Act powers. What happened?

Well, yes, as you may have guessed; I have a candidate explanation.

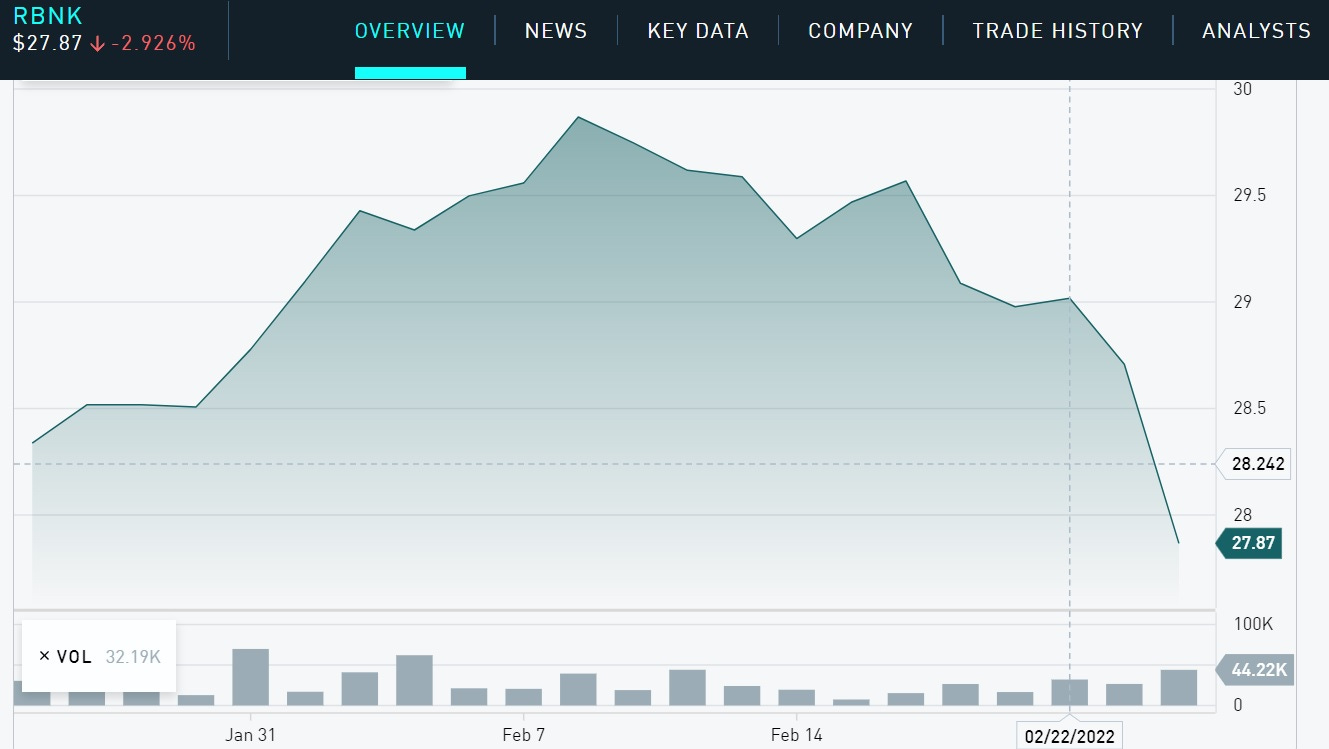

Have a look at the Toronto Stock Exchange valuations of Canada's big five banks, starting on 02/22/2022, accelerating into February 23.

Bank of Montreal

Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce

Royal Bank of Canada

Scotiabank

Toronto Dominion Bank

Do you detect a pattern? Is it possible international investors are reluctant to do business with financial institutions subject to political weaponization against critics of the government?

Some have suggested to me that this dramatic downturn in the financial fortunes of the banks was due to the supposed “run” on the banks by ordinary Canadians. As I’m not an authority on financial institutions, I turned to my brother, who has been a registered broker and worked in the financial sector, both as an independent and in-house trader, as well as for a bank. Here was his assessment.

This had to be the big boys. When stocks fall as fast as those bank stocks did, it’s generally because not only did the sell orders far outweigh the buy, but also the price began moving down quickly enough that it triggered robot trades which drove the price down further which triggers more robots until a human intervenes to pause the computer trading algorithmic cascade. This is the domain of the big boys. Everyday mom and pop traders have neither the cash nor stock volume to initiate such a move. And contrary to what many think, banks aren’t really that concerned about front door deposits: they’re mainly offered just to be in legal compliance. The level of a front door cash run required for that effect would have to be beyond comprehension. Plus, the effect of such a run would take a lot longer to be noticed by the market as long as the big boys were happy. This was the work of mutual funds and large institutions.

And who runs those mutual funds and large financial institutions? That’s right, members in good standing of the managerial class. As I emphasize in my book, The Managerial Class on Trial, the managerial class is distinguished in their specific relation to the mode of production as symbol manipulators. While the emphasis in this substack has been on the manipulation of language symbols (e.g., here and here), the manipulation of numeric symbols is no less important to their success; that’s how they’ve generated the modern, computer-powered, finance industry. That’s an important discussion all its own, but let’s get back around to my main point in this post.

The faction of the managerial class that runs the puppet show known as Justin Trudeau saw an opportunity to crush the populist insurgency, perhaps for a generation, by aggressively eradicating all its capacity and support, root and branch. However, in their enthusiasm to achieve this agenda, they trampled upon the toes of other, equally powerful factions of the managerial class: international investors who didn’t trust their resources being within reach of the Trudeau Show, which ranked its political objectives above the interests of those trying to generate and maintain financial empires. As a result, once the big five Canadian banks saw their stock values crashing, the phones calls which the rest of us never get to hear about, and that never go to voicemail, started flying through the proverbial wires. The puppet show known as Justin Trudeau needed a sudden mid-season plot course-correction to avoid open hostilities with a faction of its own class which could have done it tremendous damage if it chose.

So, enjoy your white pill while it’s on offer. The ruling class is not monolithic and no matter how powerful and power hungry any one faction of it may be, it always must contend with the conflicting interests of other factions of the managerial class. This is never a guarantee that dark forces won’t have their way, but it should be a reassurance that no matter how powerful any ruling class maneuver may seem, neither is its success ever guaranteed, either. The world is a complicated and conflictual place – even for the ruling class. And, maybe even especially so for the rule of the managerial class. That’s a topic to be further addressed down the road. For now, take some solace from recognizing that the ruling class is never as powerful as they’d have you believe. They’re as much victim of their human complications, frailties, caprice, and hubris as are the rest of us.

To be clear, in this post, when I refer to “Trudeau,” unless the reference is obviously of a personal nature, I am in fact referring to the Liberal Party power trust being run out of the PMO (the Prime Minister’s Office); it is not clear to me that Justin Trudeau runs (or is capable of running) anything, nor that he is anything more than a well packaged front boy for those who are really devising the strategy and making the real decisions. For an analysis of how political power in Canada has increasingly concentrated in the PMO, see: Donald Savoie, Governing from the Centre: The Concentration of Power in Canadian Politics (Toronto ; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 1999).

In theory, Trudeau eliminated party affiliation as an appointment criterion, though it’s questionable whether this reform is anything more than a formality. In the process, though, his emphasis in senator selection on grievance identity markers (gender, race, etc.) has ensured that the performative ideology of the managerial class and its bureaucratic paternalism is institutionalized within the Senate. This combined with a selection emphasis upon managerial class acolytes hardly boded well for an outcome sympathetic to the populist uprising represented by the trucker-inspired movement. For a discussion of all these aspects of the current Senate, see: Donald J. Savoie, Democracy in Canada: The Disintegration of Our Institutions (Montreal ; Kingston ; London ; Chicago: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019), chap. 9. For discussion of the role of bureaucratic paternalism for the managerial class and its administrative state, see my book, The Managerial Class on Trial.

These numbers are taken from the Wikipedia article. While one shouldn’t put much stock in anything on Wikipedia which is sensitive to contemporary “culture war” maneuvers, I trust they can get this kind of thing right (at least for now): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_current_senators_of_Canada

Finally, thanks to Ontario Superior Court Justice Alex Pazaratz, there appears to be the beginning of some pushback in the courts against this slavish deference to the government’s monomaniac policy focus and its demonization of dissident views: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2022/2022onsc1198/2022onsc1198.html