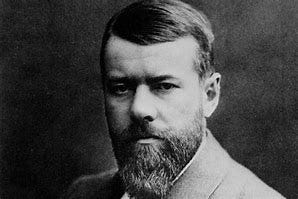

In this post I continue a mini-project of fleshing out a bit the lessons from the origins of sociology in its documentation of the liberal defeat of pluralism, as sketched out in the work of Robert Nisbet. Furthermore, I’ve been fleshing out these sociological contributions, and the entailed social theory, with an eye to how they dovetail with the earlier, more expansive project on this substack of sketching a coherent strategic objective for populism as an agent of a renewed organic community. In this post, I’m turning to the contributions in this direction of the work of Max Weber.

In the last post, I provided a lengthy treatment of Tönnies’ seminal work on the social distinction between what in German he famously identified as gemeinschaft and gesellschaft. There’s some nuance in these terms, and controversy about their best translations. I won’t repeat all that here and encourage the curious reader to review that last post. I fleshed out his argument with insights from an evolutionary psychology which he simply didn’t have access to, writing in the late 19th century. In the end, I hope to have established that in a very literal sense gemeinschaft referred to an organic community, while gesellschaft referred to more formalized associations that relatively speaking lacked such organic fiber.

In that post, we saw the interesting way in which Tönnies’ analyses overlapped with that of Harold Innis, and his emphasis upon time and space bias. The gemeinschaft was the world of the temporals; the gesellschaft the world of the spatials. While in some ways Weber’s analysis obviously draws upon the initial observation provided by Tönnies, his theoretical elaboration in fact takes the gemeinschaft-gesellschaft analysis even further into an elegant dovetail with Innis’ insights.

I’ve worded the title this way because having already established the thought of Innis, we’re looking at Weber through that lens. The latter, though, was the older of the two. Weber died in 1920, the same year that Innis received his doctorate from the University of Chicago. As we’ll see, it would have been reasonable to think Innis had been deeply influenced by Weber. However, electronic searches of Innis’ communication/civilization books show virtually no mention of Weber at all. It’s possible that they both simply noticed the same things.

Teasing a systemic understanding out of Weber on these topics is more challenging than it was with Tönnies. The latter literally wrote the book on the topic. Plus, he was not shy about explicitly stating his theoretical positions unambiguously. Fleshing out Weber’s take on the topic is considerably more challenging. There is no single work that focused explicitly/exclusively on the topic. While he does regularly address both sides of the equation, such discussion is woven through his work, appearing in many different treatments of a variety of related issues. And just to make things a little bit more complicated, Weber’s theoretical axioms are almost always embedded in categorical and definitional discussions.

So, while Weber’s contribution is substantial, and has been extremely influential, it’s not easily isolated in a handful of pithy quotations. Plus, the effort to distill Weber’s insights on the topic are further aggravated by his rather dry writing and analysis styles. Weber was concerned with the importance of a dispassionate, clinical sociology. I fully endorse this aspiration to aim for rigor over sensation, though I’m not convinced that that ambition necessarily entails such wooden style. Still, having gone through several of the widely acknowledged as most relevant essays and book sections, buttressed by secondary sources – beyond Nisbet – I do finally feel as though I’m able to provide at least several valuable, if preliminary observations on Weber’s contributions to the discussion of gemeinschaft and gesellschaft: particularly as they dovetail with our Innisian temporalist-spatialist model.

There’s in fact three points I’d like to emphasize here: 1) Weber’s more dialectic modelling of the gemeinschaft-gesellschaft tension, treating it as dynamic; 2) the central importance in that dialectic which he attributes to rationalization (with some speculation about what 1 must mean for 2); and 3) a valuable distinction Weber provides that allows us to better diagnosis the two sides of Janus-faced spatialism.

As it’s the first two points which are the most important for our purposes here, I’ll just briefly start with a few words on point 3. Regular readers will be aware that I’ve increasingly concluded that, indeed, as the victors do write the history, the original “right,” which I’d also call temporalist, political vision has been written out of that history. Instead, the terms “left” and “right” have been rejigged to create the illusion that the only real question is whether we’re to come down on the side of the radical individualism of unfettered free markets, on one side, or the social engineering of the interventionist administrative state, on the other hand. This is the limit of debate, the full range of the Overton Window.

What this theoretical rejigging and rewriting of history obscures is that these are both left wing (or spatialist) strategies, each of which entails and requires sustained attack upon the intermediary institutions of organic community which have historically protected people from the jealous power of a centralizing sovereign. And just as much a product of that winners’ Overton imposition upon our history has been the idea that unfettered markets and sovereign states are in some kind of existential conflict. It’s a Herculean zero-sum struggle to the death in which only one can survive to the degree the other is vanquished. And so on and so forth with the nonsense. On the contrary, rather than competitors, these two left strategies are symbionts, mutually dependent upon each other for their survival. This has been discussed at length in many other posts to this substack (see, for example, here, here, and here.)

I’ve come to call this left strategy complex (masquerading as a dichotomy) the Janus-faced beast. Or some such. Weber, though, offers a valuable insight into how these two faces, or strategies, might be more usefully analyzed. As will be addressed further below, among the many categorical distinctions provided by Weber is between, on the one hand, types of authority, and on the other hand, forms of social relations. Broadly, authority explains the qualities that accrue influence within a specific historical-social context. Social relations refer instead to mechanisms by which members of a society interact. One of Weber’s types of authority, as again we’ll return to below, is rationality. And the most thoroughly elaborated expression of such rationality is the bureaucracy. Such bureaucratic rationality is of course the sinews of the social engineering, administrative state. The world of market exchange, though, for Weber, is a specific kind of social relation. So, restating the points from above, the interventionist, administrative state is the historic left’s authority type, while the deracinated individualist market is its social relation type.

This struck me as an interesting wrinkle in the theorizing of the left/spatialist strategy complex. I’ll have to ponder it further to see how valuable a contribution it is to a fuller theorization. But I thought it was worth mentioning. With that said, now let’s get to the main attraction: exploring Weber’s contribution to an Innisian framework for a pluralist populism, in the context of the last post’s analysis and revision of Tönnies.

Tönnies, as we saw, treats gemeinschaft-gesellschaft as a more or less fixed spectrum across which European society has moved (and probably societies in general would be expected to move) from left to right. Though, funnily, in philosophical terms, as discussed elsewhere on this substack (here, here, and here), it would be better described as right to left. But, whatever, the point is that the tendency is for a society to change from gemeinschaft to gesellschaft. And it seems that Tönnies doesn’t partake of the notion that moving back is possible. There’s some interesting dispute in the literature as to whether Tönnies considered one or the other as the better form of society. My, admittedly, limited reading of his book didn’t convince me of either of those claims. But neither is a preference of Tönnies relevant to this observation. The movement occurred, and the consensus seems to be that he considered it a one-way road.

In this regard, Weber was importantly different from Tönnies. Weber did use the terms, and it seems likely he at least to some degree was taking them from Tönnies. However, in the regard addressed just above, his uptake of the terms was quite different. This distinction was captured in the fact that Weber introduced an additional paired set of terms which echoed Tönnies’. These were the terms vergemeinschaftung and vergesellschatung. Again, translation is a little tricky. When I stuck the former into a translator, it came out as “communalization.” Another commentator said that vergemeinschaftung should be understood in English as something like “gemeinschaft-ing.”

Whatever the best way to frame this in English, what comes through is the idea of movement: i.e., the movement in the direction of being more gemeinschaft-ish. Likewise, of course, vergesellschaftung would be moving in the direction of being more gesellschaft-ish. But the very use of the word vergemeinschaftung indicates the important difference from Tönnies in Weber’s use of the concepts. As we just observed, Tönnies’ reading of the social movement didn’t seem to leave any place for something we’d call vergemeinschaftung. Movement for him was only in the direction of gesellschaft. Believing that a social order could become more gemeinschaft, than it’d previously been, was a significant move away from Tönnies’ position by Weber.

And there was a further subtlety in Weber’s usage of the terms that distinguished his thought from Tönnies. Like Tönnies, Weber characterized particular social orders as being either gemeinschaft or gesellschaft. Whether a particular society was to be characterized as either one or the other was a function of which were the more widespread social practices. However, that did not imply that – except maybe at some extreme idealist end of a spectrum – that all the relations or practices of any social order would be characterized by the same form of relating. So, it was certainly possible for a primarily gemeinschaft society to have nested within it gesellschaft relationships and practices. And it was certainly likely – maybe even inevitable – that a primarily gesellschaft society would continue to have nested within it gemeinschaft relationships and practices.

On the latter prospect, for instance (using an example from the last post), we’ve seen through history how ethnic/racial migration into large urban gesellschaft contexts have manifested in the gemeinschaft settings of Chinatowns and Little Italies. Indeed, as late as the 2000s, when I was living in Toronto, there was a street in Little Portugal on which – at least along a significant stretch of it – virtually all the residents had immigrated from the same small Portuguese island. And while ethnicity/race is a valuable glue, other city neighborhoods likewise might maintain something of the urban village quality. Also, of course, closer knit families – resisting the familial corrosive effects of gesellschaft life – remain expressions of gemeinschaft. Other kinds of associations, clubs, fraternities, etc., might serve this purpose, too. Though, according to some of the pioneering sociology work, much of this gemeinschaft space within the larger gesellschaft has been eroding already in the 20th century.1

And, on the other side of the ledger, if a gemeinschaft is to go vergesellschaftung, obviously it must begin somewhere. There must be some gesellschaft relations and practices somewhere, that can be expanded, eventually displacing gemeinschaft tendencies. And as we noted in reviewing the work of Polanyi, even amid the highly gemeinschaft world of medieval pluralism, there still were markets.2 They may have been greatly restrained, compared to our contemporary expectations. And certainly, they were restricted to properly speaking commodities – rather than, say, including land and labor. But they included the reality of traveling merchants, bringing commodities from sometimes great distances, giving rise to trading among those who had no, or at least much less, organic relation to each other. There’s no certainty that such gesellschaft aspects of a gemeinschaft gives rise to vergesellschaftung, but it provides the seeds for that possibility.

In all of this, then, we should be immediately struck by the far greater similarity in Weber’s thinking to that of Innis than we saw in Tönnies. In my post on Innis, you may recall, I emphasized his notion that time and space biases within civilizations were subject to change. Innis thought, as in the case of ancient Egypt, that this was due to the uptake of a differently biased communications medium. As I suggested in my post, I suspect he had the causation vector backward, but whatever the correct explanation for causation, Innis acknowledged both a pendulation capacity within specific societies, and emphasized his conviction that in fact there was the potential for an ideal balance of time and space biases that protected the more balanced society from the collapse risks posed by excessive bias in either direction.

Weber’s concepts of vergemeinschaftung and vergesellschaftung lends themselves to drawing such Innisian conclusions about the potential for (if not the likelihood of) shifting emphases within societies back and forth between greater or lesser gemeinschaft and gesellschaft. Indeed, they at least invite speculation about whether there might be some kind of sweet spot in such movements. I’m unfamiliar with Weber ever claiming such a sweet spot existed, much less advocating for it, as Innis had done.3 But Weber’s framing of the dynamic obviously presents such a claim as at minimum a valid consideration. So, there’s a compelling overlay in superimposing Innis’ model with Weber’s. For that reason, going forward, I’ll consider it perfectly reasonable to meld these models, and use gemeinschaft as a synonym for Innis’ time biased society: the organic community rooted in considerations of historical duration, tradition, and customary law and institutions. Likewise, gesellschaft will serve as a synonym for Innis’ space biased society: the formal, rationalized society, rooted in expansive administration, commerce, and militarism.

This dynamic, which we might call a dialectic, for Weber is primarily driven by the power of rationalization. To flesh this out, it is worth recalling that Weber distinguished between three types of authority. These he identified as being traditional, rational, and charismatic. The latter category is quite interesting generally, but of less value to the present discussion. And, in any event, according to Nisbet, he saw charismatic authority as eventually being normalized into one of the other two. So, for our purposes it is traditional and rational authority that are of interest.4

Bearing in mind an important wrinkle, relevant to the above observations and which I’ll expand upon below, some of Weber’s interpreters say that he believed that gesellschaft grew out of gemeinschaft, and not the other way around. (To repeat, if this sounds contrary to what I just said above, hang with me; I’ll get to unpacking it.) For Weber, the primary mechanism for this growing out of gemeinschaft into gesellschaft was rationality, and more to the point, its institutional systemization in the form of rationalization. While Weber may not have mined the biological roots of this impulse, for anyone with the requisite background, it is clearly implicit in Weber’s thinking. Humans, like all animals, have an evolved disposition to optimize limited resources. Every animal has a limited caloric budget – limited by its capacity to accumulate and consume nutritional resources.

The more we can make out of that budget, the better our fitness. So evolutionary selection favors traits that provide such optimizing of the caloric budget. Humans are especially interesting in that we have unusually high caloric demands because of our weirdly huge brains – which consume something like 20 percent of our caloric energy. It is these huge brains though that have provided us with a remarkable capacity for symbolic abstraction. That capacity allows us to simulate future possibilities, including the capacity to – in relatively short order – subvert the defenses of other species, which have taken (in some cases) millions of years to evolve. Some evolutionary theorists have characterized this unique dimension of the human condition as occupying the cognitive niche.5

One of the primary manifestations of our entry into this cognitive niche is the remarkable growth of our means for rationalization, as Weber observed. It was the institutional formalization of this rational capacity that Weber saw as gradually transforming social practices, and the conditions of authority, away from a gemeinschaft basis into an increasingly predominant gesellschaft set of practices and relations. The primary institutional manifestation of this tendency, as Weber famously observed, was the rise within gesellschaft of bureaucracy. The formalized bureaucracy leveraged technical knowledge and skill to optimize the human need for security and well-being in the face of a challenging natural world. The bureaucracy provided an efficiency in resource optimization that made it a powerful force in meeting human needs, allowing humans to collectively get the most out of their individually limited caloric budgets.

To this extent, Weber was unambiguously positive about the contribution of rationalization and bureaucracy to human life. Parents didn’t want to see their children die in infancy. None of us wanted to be continually subject to the vagaries of exposure, famine, or pestilence. As ever-increasing rationalization provided more and more complex systems, from agriculture, through urbanity, to industrialization, the risk of human existence was reduced to our resounding benefit. At the same time though, Weber recognized the inevitability of tradeoffs in such developments and realized that such rationalization ultimately was a double-sided blade.

First, there was the principal-agent dilemma. With time, the bureaucracy becomes a power unto itself. It’s leveraging of its technical knowledge upon resources can be, and often so becomes, more focused on the benefits achieved for the bureaucracy itself, or its members, rather than those of the societies or regimes which are supposed to be their formal responsibility. This of course – as has been discussed at great length on this substack, as well as in my (must read!) book – is the source of the managerial class’s rise to power. Rationalized bureaucracy is eventually the tool of the power grab of the managerial class.

Concerning as this development may be though, Weber discerned an even more fundamental concern with this form of bureaucratic rationality driving vergesellschaftung. In a somewhat disputed translation choice by Talcott Parsons, the final pages of Weber’s classic book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, describe the logical consequence of the aforementioned processes as resulting in an “iron cage of rationality.” While Parsons may have taken a bit of poetic license in his translation, it doesn’t seem as though his choice was that far wrong from the spirit of Weber’s analysis.

Weber observed that this bureaucratic rationality had its origin in military practice, and only later extended to the larger society. Central to its success was the necessity of individuals under this rational authority to submit themselves to its dictates. The rationalizing, and so resource optimizing, power of such a bureaucratic system was dependent upon the subordinates submitting to the logic of the regime and its rules. So, the benefits of security and even prosperity provided by bureaucratic rationality entailed a requirement of increasing human surrender of personal freedom and independent judgment. This tradeoff for Weber was essential and instrumental to the very nature of gesellschaft, and of course vergesellschaftung.

The more a human society pursued the freedom from want and privation associated to a more naked exposure to the harsh Darwinian conditions of the natural world, then, likewise the more human freedom was sacrificed in the demand to submit to the rational bureaucratic machine, to become but a cog in its effective operation. It was in this sense that Parsons evidently felt the English translation of “iron cage of rationality” captured the spirit of Weber’s analysis (regardless of what technical accuracy it lost from the original German.6 )

And so, we seemed to become ever more firmly locked into that iron cage: the more we sought freedom from the harsh Darwinian conditions, the more we lost our social freedom; the more the cage’s iron grip tightened. It’s a bleak picture he draws. At least within the logic of this analysis, Weber doesn’t seem to provide any grounds for hope that this iron trap can be escaped.

And yet, as we’ve seen, Weber fully acknowledges the capacity for vergemeinschaftung (gemeinschaft-ing); he recognized a dialectic at work between gemeinschaft and gesellschaft.7 So, what can he have meant by saying gesellschaft only grew out of gemeinschaft, not the other way around. Or that the grip of the iron cage was evidently ironclad? On the face of it, these positions seem mutually contradictory. And in my reading, I haven’t found any explicitly expressed theoretical reconciliation of these positions.

However, while I concede this interpretation is speculative on my part, there strikes me as being at least one obvious theoretical path of reconciliation. And, as it happens, it’s an explanatory model which again dovetails elegantly with our Innisian analytic framework. That is, to say that gesellschaft grows out of gemeinschaft is to say, like a plant developing from seedling to full growth, there is an emergent process built into this dynamic. That though doesn’t say there’s no returning to gemeinschaft from gesellschaft, only that a metaphor of growth is not the relevant one. Rather, the appropriate metaphor for a definitive vergemeinschaftung is something more like collapse.8

And Weber acknowledged that there was a process of self-defeat in rationalization’s vergesellschaftung. Eventually, the endless and merciless pursuit of rationalization winds up undermining the very promises which had initially underpinned its authority and legitimacy. Security and freedom, initially the fruits of bureaucratic rationality, wind up becoming poisoned fruit. Rationalization winds up resulting in irrationality, by its own terms. The promise of the rationalist project collapses.9 And so, especially given our long history of (Innis’ space biased) civilizational collapse, it seems perfectly plausible that all Weber meant by restricting “growth” to vergesellschaftung is that vergemeinschaftung manifests differently. In social collapse, which then sees renewed gemeinschaft rise once against – like Medieval Europe out of the Roman Empire – from the debris of the rationally-exhausted gesellschaft.

At this point, then, I trust the overlap between the models of Innis and Weber is becoming clear. Both see the world in a continual movement between time biased/gemeinschaft and space biased/gesellschaft social/civilizational tendencies. Both recognize the promise, yet also the risks and limitations, within each social option. Both recognize that over time each tends to give way to the other – even if in one direction the giving way is primarily through calamity.

There remains though apparently that one striking difference between their positions. And their differences highlight a compelling question, which however cryptically has been increasingly informing my thinking through the issues of this substack for a while now: might something like pluralist populism yet play an important role, amid our current creep toward civilizational collapse, contributing to the possibility, which at least Innis seems to have left open, for a pendulation in lieu of a catastrophic fall?

That after all is the only reading that makes any sense of Innis’ famous “plea for time.” It’s not so clear that Weber granted that prospect. So, at this point, I feel the need to empirically treat this as an ongoing, open question. Though, in the absence of a definitive conclusion on the matter, it seems like not only an optimistic, but a prudent, position to at least continue in the hope that some kind of populist resistance may yet provide us something of a softer landing in the otherwise grim prospects that seem likely to lay ahead.

And if that hasn’t totally bummed you out… Which really it shouldn’t have; it was kind of white pilled, in a convoluted sort of way. Anyway, if you find some value in such musings, and you haven’t yet, please…

And if you know any masochists on whom you’d like to inflict just this very special kind of suffering, please…

Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, Revised, Updated ed. edition (New York London Toronto Sydne New Delhi: Simon & Schuster, 2020).

While writing this, I’ve just come across the thought of John Milbank, who makes the valuable distinction between markets and marketplaces. The former refers to the abstract market, post Polanyi’s great transformation, which dissolves everything into a commodity form, including land and labor. The marketplace refers to the pre-great transformation period, in which exchange was segregated to specific geographic location, subject to forms of regulation that reduced its socially corrosive effects.

Though, I will note that Nisbet clearly thought Weber granted the possibility of such a sweet spot, indeed in terms that strikingly echo Innis: “it is possible to see in Weber’s mind an appreciation of the moral value of a mixture of all three [authority] types. A society governed by traditional authority alone would be static, undoubtedly inegalitarian, and without the resources of reason ready to be activated. Similarly, a society governed entirely by the personal charisma of some one individual or tiny group would surely verge on a condition that could range from despotism to fanaticism if long continued. A social order composed of charismatic individuals would be, of course, an impossible one. It is, in short, a society combining all three types of authority, and with these the social groups and strata which provide diversity and the possibility of change, that Weber clearly prefers. He was himself a man of profoundly liberal tendencies, but his preference for monarchy reveals that he could see many of the same possibilities of regimentation and monolithic collectivism in mass democracy that Tocqueville had seen.” Robert Nisbet, The Social Philosophers: Community and Conflict in Western Thought (New York: Pocket Books, 1983)

It may be of interest to note that, in Weberian terms, populism recently has been fighting bureaucratic authority with charismatic authority (e.g., Trump, Bolsonaro, Orbán). To succeed ultimately it must confront bureaucratic authority with traditional authority. The question is whether the former can be a successful vehicle to the latter. Weber offers a mixed verdict on that. Charismatic authority has served that role historically, but of course he sees it being gradually eliminated by rational/bureaucratic authority in the modern world. Whether a push back is possible is an important question addressed in the text of this post.

H. Clark Barrett, Leda Cosmides, and Tooby, “The Hominid Entry into the Cognitive Niche,” in The Evolution of Mind: Fundamental Questions and Controversies, ed. Steven W. Gangestad and Jeffery A. Simpson, 1 edition (New York: The Guilford Press, 2007); Steven Pinker, “The Cognitive Niche: Coevolution of Intelligence, Sociality, and Language,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, no. Supplement 2 (2010): 8993–99, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0914630107; Andrew Whiten and David Erdal, “The Human Socio-Cognitive Niche and Its Evolutionary Origins,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 367, no. 1599 (2012): 2119–29, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2012.0114. Also, for those interested, I’ve explored the relevance of these developments for human communication and its deep social functions: Michael McConkey, Not for the Common Good: Evolution and Human Communications (Vancouver, B.C.: Biological Realist Publications, 2016).

The more technically accurate German would be something more like “iron shell.” And I’ve read arguments about why this wording invites some more nuanced potential interpretations of what Weber was getting at. It seems to me though that anything Parsons’ choice may have lost in nuance or precision it more than compensated for in its vivid capture of the core dynamic in Weber’s analysis. So, at least for now, I’ll stick with it.

In fact, in a rarely captured moment of expressing a personal opinion, free from his usual dedication to scholarly impartiality, he gave every reason to believe he didn’t in fact think that gesellschaft’s iron cage of rationality was inescapable, at least in principle: “It is horrible to think that the world could one day be filled with nothing but those little cogs, little men clinging to little jobs and striving towards bigger ones—a state of affairs which is to be seen once more, as in the Egyptian records, playing an ever-increasing part in the spirit of our present administrative system, and especially of its offspring, the students. This passion for bureaucracy ... is enough to drive one to despair. It is as if in politics...we were deliberately to become men who need ‘order’ and nothing but order, become nervous and cowardly if for one moment this order wavers, and helpless if they are torn away from their total incorporation in it. That the world should know no men but these: it is in such an evolution that we are already caught up, and the great question is, therefore, not how we can promote and hasten it, but what can we oppose to this machinery in order to keep a portion of mankind free from this parceling-out of the soul, from this supreme mastery of the bureaucratic way of life.” From Frank Elwell’s faculty page: “Max Weber on Bureaucratization in 1909,” accessed May 2, 2023, https://www.faculty.rsu.edu/users/f/felwell/www/Theorists/Weber/Whome3.htm.

I suppose, if one really wanted to press the plant metaphor, a return to gemeinschaft might be more like the death of the plant and its organic breakdown to fertilize the soil. Which, of course, would lay the ground for the emergence of a new seedling, and so on.

It’s worth mentioning here that all the knee-jerk dismissal of postmodernism by those on the so-called right fails to appreciate that at least in this regard, postmodernism is a profoundly right wing (which is to say temporalist) insight. Modernism – the left project of rationalist gesellschaft, with its social engineering and unfettered free market ambitions – has a built-in expiration. The best of the postmodernists (before postmodernism was hijacked by disaffected Marxists, following the fall of the Soviet Union, in the 1990s) were merely observing this sociological reality. Though I’d say none of them did so with nearly the rigor of Weber, half a century earlier.

I must say I don't like the Gemeinschaft / Gesellschaft binary. I would like a three-way split, with Gesellschaft meaning social -- "mein Gesell" translates as "my companion" -- and Rangordnungschaft meaning hierarchy.

Suffering is no big deal as long as you can find a meaning in it 😉