In my (must read) book, The Managerial Class on Trial, I introduce the analysis to be offered as being a form of “right wing Marxism.” Okay, I concede, there was a mischievous element to that rhetorical flourish: taking pleasure in blowing up minds on both sides of the conventional left-right divide. And there is value in simply challenging people to think beyond the comfortable confines of their well-worn theoretical priors. There really was though some truth in the idea that at its core Marxism does provide a valuable sociological (I’d even say sociobiological) tool of analysis once shorn of its debilitating Hegelianism – which is what infuses conventional Marxism with its tedious and ludicrous teleology and faux eschatology.1 I’m not saying Marxism is perfect or sufficient once shorn of the Hegelianism; Marx’s over-reliance on Ricardo’s labour theory of value also led him astray. That’s though just being wrong, the problem with conventional Marxism is the kind of wrong produced by the excessive resort to Hegel.

Liberated from Hegel, though, Marxism is not only of value for a general-purpose social analysis but, as it happens, it’s doubly pertinent for an analysis of the managerial class – the main player in the aforementioned book. As I’ve argued in that (must read) book, this new symbol-manipulator class used its linguistic and numeric dexterity to take advantage of the conditions emerging with the Second Industrial Revolution, of the late 19th century, to maneuver itself into the position of the new ruling class. Part of the cleverness of this new, emergent ruling class’s strategy was to keep itself invisible, effectively manipulating already prevailing class conflicts for its own class interests. They needed to displace the bourgeoisie, but the best way of doing so was to maneuver the proletariat against the bourgeoisie.

As I explained at length in the (did I mention, must read?) book, this strategy explains the otherwise peculiarly imprecise place of Marxism (and indeed Marx himself) within a Marxist analysis.2 Marxism purported to be the voice of the working class, or proletariat, but in fact those who spoke the theory and language of Marxism were not themselves industrial (or even agrarian) workers. Instead, they were this new class of intellectuals, journalists, engineers, academics, lawyers, etc. It served their interest to mobilize the workers against the bourgeoisie, while not drawing attention to how they were in fact slowly displacing the bourgeoisie as the new ruling class.

This strategy is accomplished through an ideology which rationalizes the role of this new ruling class, while simultaneously deflecting attention from the fact of their rule. This is always true to the extent that a ruling class has members of the managerial class working for them, to achieve such ideological ends. It was doubly true once the managerial class started acting directly on behalf of its own class rule.

So, the requirements for achieving this transfer of class power involved both, obscuring the actual role of the managerial class, while ostensibly empowering the working class in their phantom struggle against the bourgeoisie. It was these concerns that led me in the book to characterize the managers as a ventriloquist class. With their clever, dexterous manipulation of language, they proved capable (indeed, I’d say increasingly capable) of molding the perception of reality held by many in the working class. This tactic was bolstered by their exploitation of the concept of democracy. A term so uncritically salutary today, that it’s easy to forget that prior to about a century ago the term was not especially popular, and when used it often carried negative connotations. Some of the great figures of Western thought have warned against its dangers.

What many of those who warned against the dangers of democracy didn’t consider was that there might be a ruling class so adept at ideological manipulation of language, that there’d be no risk to them of popular, democratic rule, because they would be so capable of engineering what a more than sufficient number of the people believed was true. As long as their ventriloquism – their ability to place their own thoughts and words in the minds and mouths of the working class, the people – was effective, democracy was not a threat to them as a ruling class, but rather a facilitating myth. Sure, the people could choose democratically, we’ll just tell them what they want to choose. Seen through that lens, we’d expect that the popularity of the word “democracy” should correlate with the rise of this managerial class.

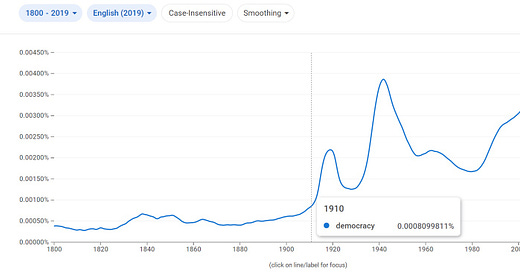

For readers unfamiliar with Google’s ngram tool, it provides a great way to chart the popular use of terms in the written record over a designated period of time. The going estimation seems to be that Google has digitalized around 25 million books. This has allowed word searches that display the rising or falling popularity of the use of specific terms across many centuries. Given then my observations from above, it shouldn’t be surprising to see the remarkable growth in the use of “democracy” over the last couple of centuries.

As can be seen, after a consistently modest use going back to 1800, in the early 20th century use of the term suddenly skyrockets. A common explanation for this popularity is the use of the term as the battle cry of Woodrow Wilson with the U.S. entry into WWI. Before an April, 1917, joint session of Congress, he declared, in seeking a declaration of war, that the “world must be made safe for democracy.” First, though, such an explanation would be tautological. It would be precisely the reasons behind why Wilson and his brain trust latched onto that term that would need to be explained. Above, you’ve seen my explanation. (Wilson, a university professor by vocation, was in fact a key figure in advancing the rule of the managerial class in government.) But, in any event, as can be seen from the graph, a conservative estimate of the beginning of the term’s popularity dates from 1910, not only well before U.S. entry into WWI, but four years before the start of the war. So, clearly, something else was driving the increasingly popularity of the word. Something like, increasing recognition of its utility to the strategic agenda of the rising managerial class rule?

However, as I also noted above, central to the strategic operation of the rise of the managerial class has been its ventriloquism, which was premised on its ability to remain invisible. It would be counter-productive to their rise to power to mobilize the working class through the valorization of the trappings and aesthetics of democracy, if that working class would then be able to turn that new democratic power against the new ruling class. So, while the managerial class was leveraging the working class, through its promotion of democracy, to attack the former’s rival for ruling class power, it was essential that even as the managerial class maneuvered itself into increasing control over the newly rising mass corporations, that this fact of realpolitik not be allowed to deflect the ire of the working class from the new ruling class’s preferred target of that ire. They certainly didn’t want actual economic and political equality, they wanted their corporate power, but they needed a linguistic trick which maintained their class invisibility, even while they were taking power. If the working class made a target of some corporate plutocrat, it was important that none of that ire became focused in on their class interest and strategy. So, a term was needed that wouldn’t succumb to the delusion of denying the corporate power of members of their class but would obscure the distinctive class membership of those members.

I argue in The Managerial Class on Trial that the term which they hit upon was the idea of the “businessman.” This term maintained a delicate association to the idea of capitalist or bourgeoisie. A businessman did business, ran a business. If such a person did become the object of working-class ire, he could be associated with the old, declining ruling class, without anyone needing to quibble over whether such a person was capitalist or bourgeois in any technical sense. Meanwhile, a cloak of conceptual deniability was maintained, in which no one’s attention was being drawn to the real nature of the new, emergent ruling class technocracy and the specific traits of that class that enabled it to rise to dominance under the new economic conditions.

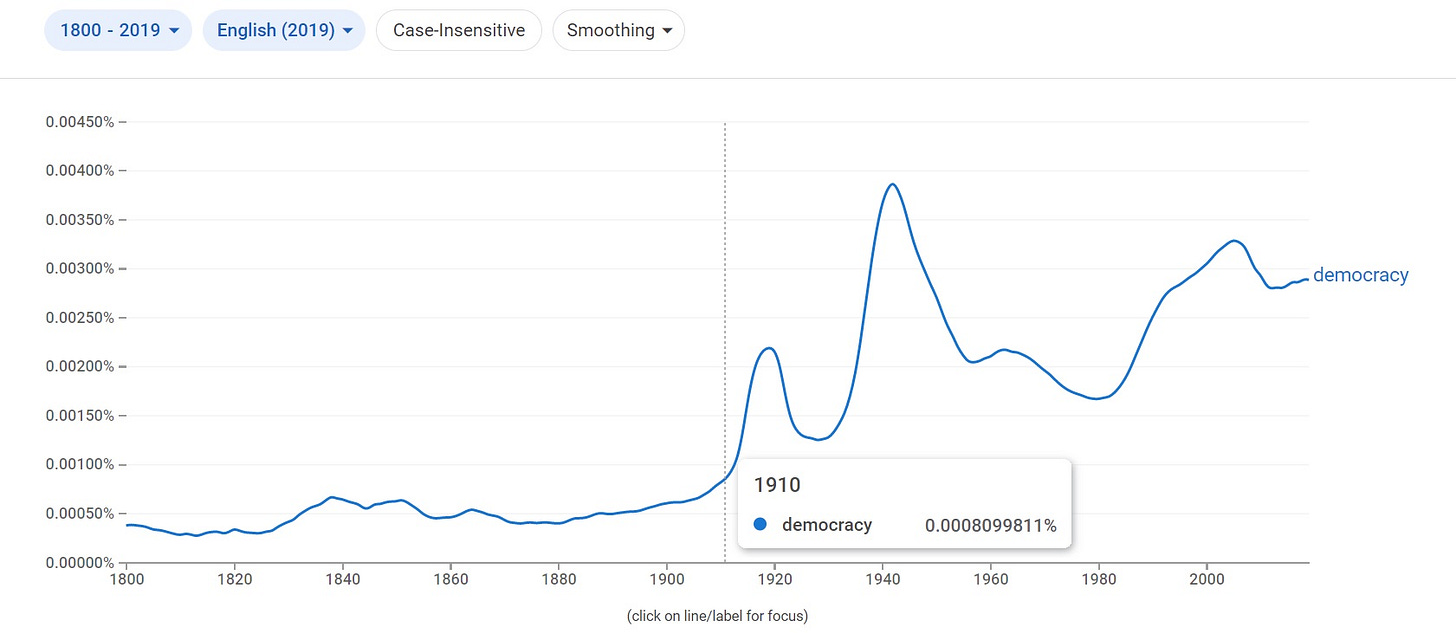

So, what do you think that the ngram for “businessman” looks like?

All this should be a sobering lesson in the managerial class’s ability to curate reality, even in the sculpting and promotion of individual words. As we now approach the point at which the managerial class’s consolidation of power is about a century old, there’s a question as to how stable it is moving into the future – particularly how stable will be the thus far triumphant “managerial liberalism” strategy of the class. As discussed elsewhere on this substack, the excess of elites always poses a threat to a ruling class, but there’s something even more fundamental than that at work.

Marx’s famous argument was that the bourgeoisie, capitalist class would sow the seeds of their own destruction. Similarly impoverishing the masses, while constructing the industrial infrastructure for a post capitalist world, he saw them as midwives of the new, post-capitalist world. Nothing like that ever came to pass. Agrarian workers have usually aspired to be bourgeois, and industrial workers have usually been content to enjoy the pleasures of an increased standard of living generated out of capital-intensive production. Indeed, from its arguable beginning in the thought of the Frankfurt School, right through the modern instantiation of intersectional politics, managerial liberalism has been largely informed by a recognition of the futility of conventional Marxism’s revolutionary agent and by extension the bourgeoisie’s midwifery.

There is a real question though as to whether, ironically, Marx’s prediction may not turn out to be much truer about his own class – despite its determination to remain invisible. Automation and computerization of the economy and society are the logical extension of the expertification of both the economy and governance. The complex of the internet, social media, data science, etc., all often evoked in the catchphrase “Silicon Valley,” is the tangible manifestation of all this. And, yes, we all know too well the benefits to the rule of the managerial class of all this. Search algorithms constrain knowledge, censorship is rampant, surveillance and coordination of e-based repressive action are made much easier than in the past.

It would be though an excessively, and inaccurately, one-sided assessment of our situation to ignore the other side of the ledger: how this same “Silicon Valley” facilitates the undermining of managerial class hegemony. Right here in this very substack post, we’ve seen how as banal a tool as Google’s ngram can be used to unmask the ideological language of the managerial class. As platforms become increasingly oppressive, alternatives appear, allowing you to leave Patreon for Locals; YouTube for Rumble or Odysee; Twitter for Gab or Gettr; Google for Brave or Searx.

Despite the effort to control information, we continue to have a remarkable repository of human knowledge at our fingers tips; even those who have been “cancelled” can be found and followed with just a little ingenuity; something like the Canadian trucker protest, which briefly galvanized people around the world, could not be smeared in the well-established method, because of the hundreds (maybe thousands) of hours of livestreaming from those on the ground; information sharing allows the media oligarchs and governments to be fact checked in real-time; social media allows instant coordination of actions; and in the case of even more pervasive suppression of information, as long as the internet continues to function, clever means can be found: such as during the Arab Spring, when protestors communicated through hidden messages buried in personal profiles on dating sites.3

As for surveillance and control, we’re only scratching the surface for what may yet be possible with the use of P2P networking, torrent and blockchain technology, and homomorphic – and other innovations in – encryption. At this point, it’s much too early to determine whether what we're headed for is more panopticon or cyberpunk.

Again, I don’t intend to make the same mistake as Marx, assuming some magical, Hegelian resolution of the contradictions in a mysterious triumph of an emancipatory spirit. That definitely would contradict the spirit of this substack. It is worth pondering though whether in fact Marx’s intuition about a ruling class playing midwife to its own replacement, or at least the means of its popular constraint4, may well apply more to his own class than the one he had hoped it would replace.

I do think that, even once freed of Hegel, Marxism still needs some important revisions to make it work. Hegelianism fills in a lot of ontological and epistemological gaps in Marxism which remain unfilled once we remove Hegel. Primary in this regard is the need to be put on a firmer biological footing. Marx was right to claim that superstructure depends on a base. However, while economics is a base to superstructure – e.g., culture, law, mores – it is not the base. Economics is itself based upon biology and the fitness-enhancing evolved disposition to maintain control over resources. But I’ll be having more to say on biological foundations in future posts over the course of spring and summer. Providing there’s not like a nuclear war or something.

It’s not a coincidence that many of the first and most insightful analysts of the managerial class were themselves dissident Marxists: e.g., James Burnham, Cornelius Castoriadis, Milovan Djilas, Alvin Gouldner, Paul Piccone.

Okay, so I remember hearing this claim at the time of the Arab Spring. However, I’ve been unable for purposes of writing this post to confirm that claim. Whether or not it’s empirically accurate, though, one can see how that kind of ingenuity can circumvent censorship efforts by repressive governments and media oligarchs.

In fact, it’s perfectly plausible that we’re headed for something resembling more the standoff anticipated by Martin Gurri in which, what he calls the centre (or hierarchy) and the border networks (or publics), in their battle over the e-media, never come to a definitive resolution: “A churning, highly redundant information sphere has taken shape near at hand to ordinary persons yet beyond the reach of modern government. In the tectonic depths of social and political life, the balance of power has fundamentally shifted between authority and obedience, ruler and ruled, elite and public, so that each can inflict damage on the other but neither can attain a decisive advantage.” He draws the analogy of suggesting that if someone from the European 17th century were time ported to our present, the first question they’d want answered likely would be, who won? The Catholics or the Protestants? We’d have to explain to them, well, neither won; they just found a new equilibrium. Maybe that’s more what lies ahead. But even if that’s true, the inability of the ruling class to rule as effectively as they have in the past still would be of historic consequences. And, if cleansed of Hegelian dialectic, maybe that wouldn’t be so far off of a Marxist conclusion about the idea of a ruling class being midwife to its own failure. Martin Gurri, The Revolt of The Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium (Stripe Press, 2018). Gurri’s is an interesting book; it would have been much better if he’d integrated the role of the managerial class, and managerial liberalism, within the story that he tells.

...and here we go, welcome to the tyranny w/o a tyrant. Hannah Arendt—a skilful linguistic symbols manipulator herself 😉—may not have had your apt term ‘managerial class’ (or a notion of its superb ventriloquist powers for that matter), though it looks like she did grasp the pernicious effects of ruling from under invisibility cloak ↓

💬 Bureaucracy is the form of government in which everybody is deprived of political freedom, of the power to act; for the rule by Nobody is not no-rule, and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.

~~

Ty an umptillion for constructing a neat dependable framework to make sense of the insane sociogeopolitical world that doesn‘t make sense at all 😊 Totally gone bonkers ← so it seemed before Grant Smith fortunately directed me to The Circulation of Elites 💯🔥

Tim Morgan is up to similar and similarly thankless task wrt a base to superstructure (not *the* base 😇) → https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com/2022/10/19/242-the-dynamics-of-global-re-pricing/

So how does the capital class (those who fund the institutions that the managerial class work at) fight back against this tactic?