This post is an installment in a longer series on Guilds, Old and New. To review a full index of all the installments to this series, see the introductory, part one of the series, here.

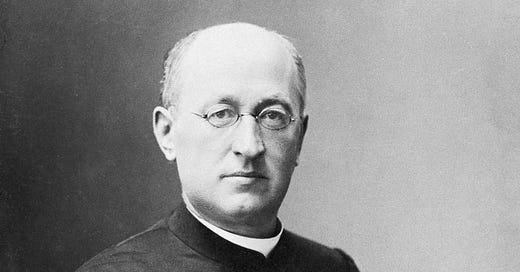

The last post reviewed the contributions of Baron von Ketteler, arguably the seminal thinker in Social Catholic corporatism. As we saw in that post, the corporatist tendency within Social Catholicism made the same mistake as North American populism, over-investing in the promise of electoralism as a vehicle for advancing its social movement goals. However, in the case of German Social Catholic corporatism, it went out not with a whimper, but rather a bang. Indeed, arguably the most ambitious vision of a Ständestaat (corporative state) was provided in these waning days of corporatist Social Catholicism, by Franz Hitze. Hitze was an influential professor of Catholic social studies and considered the father of the Catholic workers' associations.

However, as a last stand of German corporatism, it was indeed appropriate to characterize his contribution as a sign of the times, in that soon after the publication of his ambitious and influential book, Hitze himself abandoned the corporatist cause. We’ll also in this post offer some thoughts on the efforts of Peter Oberdorffer and his supporters to practically implement these corporatist ideals within Social Catholic institutions, including the Center Party, also discussed in the previous post.

Hitze, in his influential book, Capital and Work and the Reorganization of Society, and in keeping with our prior discussion of Social Catholicism, regarded free market commerce and industry as deeply destructive of Christian values. However, he also had a strictly economic criticism, resonating with the Catholic-originating distributist critique of laissez-faire capitalism.1

Like Ketteler, Hitze saw the remedy to such tendencies in the creation of a Ständestaat. Hitze though was more detailed and ambitious in his delineation of just what such a Ständestaat would look like. That seems to justify particular attention to his ideas. However, it is also true that in the process he was prepared to compromise the heterarchy of the corporations, rooting their legitimacy in the monist sovereignty of the state. In that regard, it seems to me that Hitze might be understood ultimately as a subversive figure who – however unconsciously it may have been – contributed to a “revolution within the form” of corporate pluralism.

But before we come to those assessments, let us give Hitze his due. Back to the start, let’s begin with his criticism of free market commerce and industry. As usual, we provide Bowen lots of leash in laying out his description of Hitze’s views. Bowen says that, according to Hitze:

Not only was laissez-faire capitalism unacceptable from a moral standpoint; it was not even a viable system for ordering the productive process. "Overproduction" was written on the face of the same coin which on its obverse side bore the legend, "under-consumption by the masses." The continued operation of these contradictory tendencies could produce only an unending series of booms and slumps, for it was abundantly clear, he thought, that competition was incapable of serving as a satisfactory regulator of production. It represented instead merely "a continuing process of expropriation," executed through the assertion of "the right of the strongest," and must eventually result in "the common ruin of both capital and labor."

And of course his solution lay in a form of guild corporatism, harkening back to the medieval constitution:

Only by restoring the medieval principles of "vocation" and of "mutuality," Hitze argued, could a satisfactory economic and social order be re-established.

Hitze also believed though that the guilds where in need of rejuvenation, given their corruption under the influence of capitalist pressures:

The old guilds had degenerated into rigid monopolies; therefore their decline and disappearance had been inevitable; but it should not be overlooked that in medieval times the guilds had "solved the social problem of the age" and had "guaranteed social peace to our nation over the course of centuries." In its uncorrupted form the guild system had furnished the best model for the new social organization which the modern age so desperately required "a genuine example of socialism, of communism; socialism of a sort, however, that need not terrify us."

Hitze here of course is resonating with a much beleagured tradition which I’ve identified on this substack (here), and in my book, A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars, quite correctly as right wing socialism. But Hitze’s role as a right wing socialist is not as evident as in the case of others in that tradition:

It is no longer possible to ignore the fact that a conflict exists between capital on one side and labor on the other. There remains open to us no course but to acknowledge this conflict openly, to organize it, to give it legitimate organs, to assign to it a recognized place where, under the eyes of the central state authority, the battle can be fought out.

So, we already glimpse here a role Hitze attributes to the monist sovereignty of the state, which seems doomed to undermine the corporate autonomy necessary to effective heterarchical pluralism. Still, unlike Ketteler, who’d largely based himself upon the articulation of core principles, Hitze does lay out a much more detailed version of his conceptual Ständestaat. Bowen observes that: “Hitze did not undertake to settle every detail of his proposed new order in advance. He repeatedly stressed the desirability of avoiding rigid organizational formulas and shunning arbitrary procedures.” Nonetheless, there is much more meat on this bone than was common in the German Social Catholic corporatist tradition. He starts off asserting that the various vocations of German life should be organized into seven corporate estates, then envisions a Ständestaat growing out of this corporate pluralism.

Altogether there would be seven of these estates: small landed property-owners, large land-owners, large-scale industrialists, small-scale industrialists, large-scale traders, small-scale traders, and industrial wage-earners. The crowning institution of the edifice would be a Chamber of Estates which would supplement the territorial parliament as the second chamber of the national legislature. Representatives to this Chamber of Estates would be chosen by the national electoral colleges of the several estates, these having been chosen in their turn by regional assemblies. At the base of the pyramid would be a multitude of local assemblies, one for each vocational group in a given district.

So Hitze’s model Ständestaat captures the granular centrifugalism of a decentralized federation of civic association and what today we’d call “grassroots” or “participatory” democracy. Such a pluralist corporate system, he believed, would undermine those forces which subverted legitimate popular democracy, including the monied interests; what we today call “the media”; and the corrosive effects of abstract, erratic, and deracinating individualistic majoritarianism. In Bowen’s estimation:

The social and economic interests of real, abiding functional groups would receive expression, thus lending a character of permanence and stability to legislative enactments which could never result from the "accidental," "transitory" verdicts of parliamentary majorities that corresponded to nothing more than a counting of noses.

A corporative system of "interest-representation" would also mark the final, irrevocable shattering of "Manchesterism," in that it would "end forever the domination of 'money' in politics.”

True democracy would become a reality instead of a set of empty forms. "Today we are tyrannized by slogans and 'newspapers’," but this state of affairs would have no place in the future political scheme, where corporative assemblies "would be able to express, and would express...the real desires and will of the people."

This passage, incidentally, indicates that Hitze was not naive about the dangers of what we’d today call managerial class ventriloquism (discussed in both my most recent books: The Managerial Class on Trial and A Plea for Time in the Phenotype Wars.) If I’m correctly reading between the lines, he’s arguing though that such ventriloquism relies upon the abstract representation of modern electoralism, and would be defeated by the granular associative federalism and participatory democracy of his proposed Ständestaat.

While Social Catholic corporatism tended to focus on guild pluralism – and Hitze was uncompromising in his insistence upon the obligatory nature of craft and industry corporate membership – he also paid attention to other corporate forms and practices which might contribute to, and meanwhile balance out the power of, such craft and industry corporations. Among such considerations were his role for the regulatory agency of large guilds, the function of peasant guilds, and the counterbalancing benefits of producer cooperatives.

[Craftsmen would belong to] compulsory guilds. No worker who was not a member in good standing would be permitted to engage in an occupation reserved for one of these guilds, and no one could become a member without serving a regular apprenticeship. Nor would these organizations be purely economic or technical; their scope was to be "total".

By “total,” Hitze was conceiving of those guilds as being central to the social, interpersonal, and moral enculturation of its members, much as we saw in Mack Walker’s discussion of the guilds in the context of the German hometowns (see here).

Peasants too in Hitze’s model would be bound together in their own organization, as described by Bowen:

Hitze also contemplated that many tasks of governmental administration in rural communities would be taken over by local assemblies of the Bauernstand [farming community]. These bodies would enjoy wide autonomy and would have rights of self-government which would enable them to resist undesirable encroachment on the part of the central state authorities.

Another area of encroaching central state power which Hitze’s Ständestaat would mitigate would be the area of regulation, particularly in economic areas. Rather, he conceived of the “estate of large industry” playing this role:

Public regulation of prices would have to be undertaken in the measure that reliance upon the "automatic" mechanism of the free market was abandoned. "Another medievalism!...For guilds and price-fixing are to each other as cause and effect. Whoever wants...solidarist labor must also desire...solidarist prices, and vice versa…"

Hitze specified that the goals of this regulation would be "overcoming the anarchy of production and the creation of a new spirit of social responsibility through the conquest of egoism," but he did not elaborate further upon the point.

While it would be understandable that, for some modern observers, this aspect of Hitze’s system may be pushing beyond right-wing socialism into left-wing socialism, one shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that the medieval pluralist constitution certainly involved such price regulation, both by guilds and towns.2 Indeed, such controls were considered essential to protect communities from the ravishes of unfettered laissez-faire markets.

Certainly, the rational planner, aiming for social sustainability might well express concern that such regulation exercised by the large industrial estate might be weaponized against perceived competitors, such as the small industrial estate, or the trader estates. Obviously, such potential is endemic to the human capacity for gaming any system of control, and this nature of problem is probably built into the very nature of such a large scale social engineering scheme. And, after all, as we’ll conclude below, Hitze’s whole project here has much too much of the whiff of a managerial class spatial presuming to design the ideal and rational contours of temporal organicity.

Be that as it may, to his credit, Hitze did recognize that his entire Ständestaat edifice itself entailed a danger of corruption. In that spirit he suggests a safety mechanism, in which the vertical order of nested associations and estates were to be buttressed by a horizontal order of producer cooperatives which might mitigate the corruption of the estates. As Bowen describes it:

Lest the new society of estates degenerate into a rigid system of closed castes, Hitze recommended the establishment of producers' co-operatives which would eventually make possible "the flowering of corporative life.”

In any event, Hitze concluded, some correction to the current state of conflict between labor and capital was required. Continuing down the current path offered only social destruction. Here, Bowen quotes Hitze:

Today the labor movement is a tearing-loose, a secession from the rest of society; then [under his Ständestaat] it would be a joining-on; it would be only one organization among many. The other, more conservative estates would show the workers the path...and the state would compel the workers to set themselves conservative goals and to put their own house in order alongside the ordered regiment of capital.”

However, as interesting as was Hitze’s version of corporate pluralism, upon closer examination his project does begin to take on a curious infliction. We’ve already noted features of his scheme which seem inconsistent with the temporalist values of medieval pluralism: the state invited in as referee of pluralist corporations; the concern with democracy scalable to mass society – if not exactly mass democracy; and of course the distinctive, if subtle, rationalism that characteristically animates all such plans for engineering of the good society.

There were other aspects of his vision which likewise seem incongruent with temporalist values. This included an extension of the role of the state from referee to regulator, explained as a likely concession to the very culture of capitalist industry the destructive effects of which had been the purported initiating condition for the elaboration of his corporatist model Ständestaat in the first place. And, perhaps even more telling from a temporalist perspective, was his emphasis upon an egalitarian leveling that pervaded his plan.

Bowen illustrates these tendencies in concise passages that contrast Hitze’s corporatism with that of Ketteler:

[His] heightened emphasis on the state probably reflected Hitze's keener awareness of the growing complexity of economic processes. In the sixteen years that had elapsed since Ketteler's first attempt to chart the path toward a corporative order, capitalistic economy had made impressive strides forward in Germany.

In contrast to Ketteler's emphasis upon the necessity for hierarchical differentiation of the various estates in society, for example, Hitze considered that all his Stände were equally valuable and equally entitled to be recognized as bearers of social functions, rights and responsibilities. All were to be represented on equal terms in the Chamber of Estates which would crown the corporative political edifice. Historic rights and privileges would be set aside, and the "real interests" of functional economic groups would be the sole criterion for determining the configuration and prerogatives of each estate.

Seen through this emphasis upon social leveling (though pluralist hierarchy, given the power of the role he attributes to the state), broad social democracy, and rationalist social engineering, Hitze’s project increasingly looks like a spatial trying to do temporalism. Though it might be more accurate to say that he was an aspiring spatial pluralist. The problem of course is that the rationalism, universalism, and progressivism of spatialism is fundamentally incompatible with the gemeinschaft, traditionalism, and customary law which have always been the lifeblood of temporalist pluralism.

Certainly, as we’ve seen in earlier installments to this series, egalitarianism within a corporation may arise from the binding effects of a common sworn oath, the attempt to socially generalize egalitarianism – especially as regulated and refereed by a monist sovereign – is intrinsically antithetical to the very nature of heterarchical pluralism. In this light, it hardly is surprising to learn that the author of this ambitious Ständestaat plan, delivered at the twilight of German’s Social Catholic corporatism, himself promptly abandoned corporatism for the comforting confines of establishment electoralism and what Bowen calls melorism.

Still, for all that, Hitze’s initial distortion, and eventual abandonment, of Social Catholic corporatism wasn’t quite the last word on the topic. Under the influence of Peter Oberdorffer, it still had enough juice for (in Bowen’s terms) one last rearguard action. So let’s have a quick look at that effort before drawing any conclusions about the legacy of German Social Catholic corporatism.

Bowen discusses a falling out with the Center party on the part of agrarian members, who’d originally been drawn into the party under the influence of Burghard Freiherr von Schorlemer-Alst:

Under Schorlemer's leadership, [the agrarians] even threatened at one time to secede from the party; but this split was averted, and there were no further consequences. Before the return of the disgruntled agrarians to the party fold in 1894, however, an unreconciled group of radical corporatists took advantage of this situation in order to wage a last rear-guard action against the triumphant meliorist tendency within Social Catholicism…

In June, 1894, [Dr. Peter Oberdorffer, then chaplain and later curate in Cologne] published in his magazine Koiner Korrespondenz a very detailed "Social Catholic program" which purported to be an "elaboration" upon the principles outlined in the encyclical Rerum Novarum of Pope Leo XIII (1891) and which was accompanied by a large number of supporting signatures.

The gist of this position advanced by Oberdorffer and his magazine is captured in these quotations from that program:

All Catholic social reformers consider the goal of their efforts to be the reorganization of society according to Christian principles on the basis of vocational estates (Berufsstände), in a form appropriate to modern spiritual and economic conditions, with rights of self-administration and with adequate representation of their interests guaranteed in the state constitution.

The whole structure of the state must rest on a foundation of vocational estates. The state constitution must have its foundation in the governing bodies of these vocational groups...It goes without saying that such a structure demands political representation of the vocational bodies, whether this object be achieved by a modification of our existing parliaments and their powers, or whether it be at least by the establishment of corporative chambers of equal rank alongside these.

Bowen says that this initiative by Oberdorffer and his followers generated widespread alarm within the Center Party, leading to a familiar co-optation maneuver:

...the parliamentary leaders of the Center became alarmed. They suspected that [these] maneuvers concealed an old and, to their mind, dangerous tendency that had the aim of making the Center a ''Catholic people's party," rather than a general, national and non-confessional political party. In addition, of course, the meliorist leadership of the Center's "social wing " was anxious not to have its hands tied by Dr. Oberdorffer's rather dogmatic formulation of the older school's corporatist program.

Despite strenuous attempts to prevent the Oberdorffer program from circulating widely, a further discussion of its contents took place at the Cologne Congress of German Catholics held in the summer of the same year. After a lively debate in the resolutions committee, a number of compromise resolutions were finally adopted. It had early become apparent that Dr. Oberdorffer and his radical corporatist friends were in a hopeless minority.

The adoption of this weak resolution by the whole Congress without a single dissenting vote testified eloquently to the complete rout of the extreme corporatist faction.

Bowen, in the end, draws the harsh if inevitable conclusions from the series of events recounted over these last two series installments:

Despite the tenacity with which corporatist doctrines persisted in German Social Catholicism, however, a corporative "new ordering " of society was never the program of a clear majority of the movement's leaders after 1880. By 1890 only a handful of doctrinaires and a die-hard agrarian faction within the Center were still actively promoting such a program, and the flame was subsequently tended only by isolated scholars and academicians until after 1918. The post-war revival of interest in Catholic corporatism was confined to a minority, and achieved no noteworthy practical results. The doctrine has thus largely remained the expression of an ideal, and its central significance has continued to be primarily intellectual.

But as a critique of atomistic individualism on the one hand and of state omnicompetence on the other it has contributed in a not insignificant fashion to modern Catholic political and social thought.

The history of Social Catholicism’s foray into corporate pluralism I think offers us some lessons. Too much of German Social Catholic corporatist thought manifested itself as plans and engineering projects. Such rationalist planning is intrinsically incompatible with the organic nature of family, community, tradition, fellowship, and customary law, which is at the heart of temporalism. And of course it is precisely heterarchical pluralism which allows the room for temporalists values and institutions to survive (potentially even thrive) under the hegemony of the relentless spatial revolution. This winds up as the standard managerial class co-opting of all opposition to its bureaucratic rationality.

Such observations, though, should not discourage us into thinking that there’s no place for deliberate action: e.g., activism or scholarship which might contribute to a restoration of temporal pluralism. Such efforts though must avoid prescription and normative blueprints. Rather the function of such scholarship is that of contemplating the principles, values, mechanisms, and precedents through which pluralism – ideally corporatist and heterarchical – might recover. And the function of activism, electoral or community-based, should aim at generating the institutional and territorial room for such temporal pluralism to be grown, nurtured, and cultivated through the organic processes of living communities, customs, and traditions: providing them shelter against the ambitions of the aspiring monist sovereign and the inexorable march of the spatial revolution.

We’re not quite yet done with Bowen, though, as I’d like to dedicate a post to his overall conclusions about the history of German corporatism. And in that context we’ll also have occasion to have a quick look at Bismarck’s brief flirtation with corporatism. So, to be sure not to miss that, if you haven’t yet, please…

And if you know of others who’d be interesting in joining in with our explorations here, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

For a contemporary expression of pretty much the same critique, see chapter 16 of John Medaille, Toward a Truly Free Market: A Distributist Perspective on the Role of Government, Taxes, Health Care, Deficits, and More, 1st edition (Wilmington, Del: ISI Books, 2011).

The topic of price controls is one that no doubt warrants further exploration. As I’ve been writing this post, it has been a hot topic in the U.S. presidential election, with free market commentators invoking the dark days of the 70s, with Nixon’s and Trudeau’s wage and price controls. Personally, I’ve been so disabused of formerly assumed platitudes and truisms about free markets that I’m now curious about whether those efforts were the unmitigated failure they’re always portrayed as being. That would take a closer examination than I currently have time for, but it is also true that there’s a huge different between “price controls” imposed by a monist sovereign and those “imposed” by a pluralist corporation. If corporatism is well established in the given society, such “controls” are in effect a negotiating position. The point seems to me more about manual/sinew workers enjoying shared bargaining power, so that they’re not sitting ducks for larger, more powerful economic actors to play them off against each other in “free” market competition. But there’s so much more to say about all of this, of course.