In a recent post we observed, among other media, Hobsbawm’s comments on the historical impact of the telegraph. From the perspective of Schmitt’s spatial revolution, though, there is considerably more of significance that could be observed in regards to that distinctly space biased communication medium. Toward that end, I’d like to briefly review the insights from an essay on the impact of the telegraph written by James Carey.

It’s worth noting to begin that James Carey was arguably the most influential amplifier of the seminal insights of Harold Innis on time and space bias.1 (Even more than Innis's more celebrated acolyte, Marshall McLuhan, due no doubt in considerable part to the former's greater clarity of exposition.) Carey operationalizes Innis’s space-time distinction in the bias of communications media by distinguishing between what he identifies as transmission (exogenous) and ritual (endogenous) communication.2 In this framing he is distinguishing, we could say, between reaching out and reaching in: from geography and territory to psychology and culture. With this frame in mind, then, we turn to his observations about the historical impact of the telegraph.3

Though he does discuss additional impacts and effects of the telegraph, the areas we’ll focus upon here are: the written language, with its standardization entailing the transcending of local flair, color, and idiosyncrasy, and its tending toward precision, scientific, “objective,” language facilitating the commodification of information; commodity markets; and the institutionalization of standard time zones. To begin we’ll let Carey lay out his broad-based claims about the telegraph:

...the telegraph brought about changes in the nature of language, of ordinary knowledge, of the very structures of awareness.

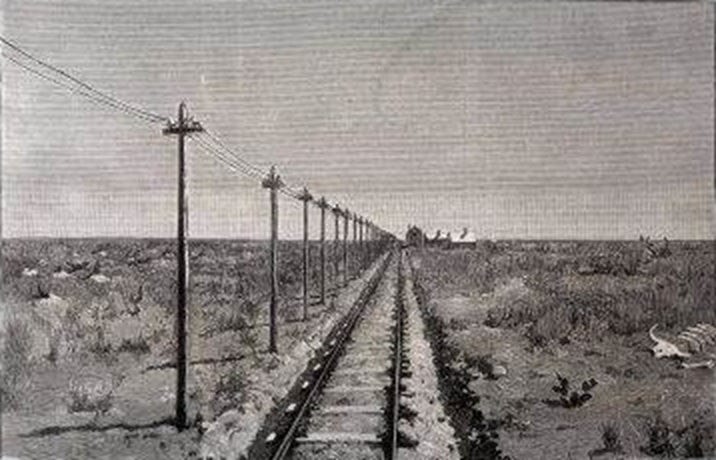

...[the] most important fact about the telegraph is at once the most obvious and innocent: It permitted for the first time the effective separation of communication from transportation.

Before the telegraph, “communication” was used to describe transportation as well as message transmittal for the simple reason that the movement of messages was dependent on their being carried on foot or horseback or by rail. The telegraph, by ending the identity, allowed symbols to move independently of and faster than transportation.

I wish to concentrate on the effect of the telegraph on ordinary ideas: the coordinates of thought, the natural attitude, practical consciousness, or, less grandly, common sense. As I have intimated, I think the best way to grasp the effects of the telegraph or any other technology is not through a frontal assault but, rather, through the detailed investigation in a couple of sites where those effects can be most clearly observed.

The first of these sites, addressed by Carey, is the impact the telegraph had upon the written word. Key to the impacts he discusses here is to remember that sending messages by telegraph was costly, and so an economy and precision of language provided the most cost-effective utilization of this new, remarkable communications medium. As it related to language, the impact of these cost-effective requirements, as we’ll see, was not merely a syntactical or grammatical effect, but one that contributed to the spatial revolution – including the erasure of local time biased culture.

In a well-known story, “cablese” influenced Hemingway’s style, helping him to pare his prose to the bone, dispossessed of every adornment. Most correspondents chafed under its restrictiveness, but not Hemingway. “I had to quit being a correspondent,” he told Lincoln Steffens later. “I was getting too fascinated by the lingo of the cable.” But the lingo of the cable provided the underlying structure for one of the most influential literary styles of the twentieth century.

The telegraph reworked the nature of written language and finally the nature of awareness itself. There is an old saw, one I have repeated myself, that the telegraph, by creating the wire services, led to a fundamental change in news. It snapped the tradition of partisan journalism by forcing the wire services to generate “objective” news, news that could be used by papers of any political stripe.

The wire services demanded a form of language stripped of the local, the regional; and colloquial. They demanded something closer to a “scientific” language, a language of strict denotation in which the connotative features of utterance were under rigid control. If the same story were to be understood in the same way from Maine to California, language had to be flattened out and standardized. The telegraph, therefore, led to the disappearance of forms of speech and styles of journalism and story telling— the tall story, the hoax, much humor, irony, and satire—that depended on a more traditional use of the symbolic...The origins of objectivity may be sought, therefore, in the necessity of stretching language in space over the long lines of Western Union. That is, the telegraph changed the forms of social relations mediated by language. Just as the long lines displaced a personal relation mediated by speech and correspondence in the conduct of trade and substituted the mechanical coordination of buyer and seller, so the language of the telegraph displaced a fiduciary relationship between writer and reader with a coordinated one.

The spareness of the prose and the sheer volume of it allowed news—indeed, forced news—to be treated like a commodity: something that could be transported, measured, reduced, and timed. In the wake of the telegraph, news was subject to all the procedures developed for handling agricultural commodities. It was subject to “rates, contracts, franchising, discounts and thefts.”

So even in the simple shifts of language style demanded by the cost requirements of telegraph use, Carey points us toward several examples of how this technology imposed the spatial revolution upon local, temporal communities. Primarily, it demanded a striped-down, standardized language that tended toward homogenization when applied within local communities; it created the impression of “objective” news that transcended local concerns and dispositions; and it lent itself to the commodification of news (perhaps even of “the new”). Though, as we’ll see momentarily, it was not only news whose commodification was enhanced and facilitated by the telegraph.

This brings us to the impact of the telegraph to which Carey provided most of his attention in this essay:

In the balance of this essay I want to cut across some of these developments and describe how the telegraph altered the ways in which time and space were understood in ordinary human affairs and, in particular, to examine a changed form in which time entered practical consciousness. To demonstrate these changes I wish to concentrate on the developments of commodity markets and on the institutionalization of standard time.

A little clarification before we move forward might be helpful. Carey uses the word "time" in a manner perfectly valid for vernacular use, but contributing to semantic muddle in a theoretical context of attempting to maintain conceptual clarity in the application of Innis' stylized use of the term – even further stylized in my hands: referring to time biased ideology and assumptions as temporalist, and personality phenotypes predisposed to time bias as temporals. I’ll actually have more to say on this topic in the next post, but for now let’s say, to avoid such semantic muddle, in many instances where Carey refers to, for instance, standardization or colonization of “time,” I'll refer (and the reader might profitably interpret such statements as referring) to the standardized coordination of clocks or the colonization of the future.

Through the telegraph and railroad the social relations among large numbers of anonymous buyers and sellers were coordinated. But these new and unprecedented relations of communication and contact had themselves to be explained, justified, and made effective.

Before the use of the telegraph to control switching, the Boston and Worcester Railroad, for one example, kept horses every five miles along the line, and they raced up and down the track so that their riders could warn engineers of impending collisions...By moving information faster than the rolling stock, the telegraph allowed for centralized control along many miles of track.

One important consequence of this liberating information from things was in an abstract spatialization of trade.

...the principal method of trading is called arbitrage: buying cheap and selling dear by moving goods around in space.

The effect of the telegraph is a simple one: it evens out markets in space.

The telegraph puts everyone in the same place for purposes of trade; it makes geography irrelevant.

But the significance of the telegraph does not lie solely in the decline of arbitrage; rather, the telegraph shifts speculation into another dimension. It shifts speculation from space to time, from arbitrage to futures. After the telegraph, commodity trading moved from trading between places to trading between times.

So, reminding the reader of my qualifications above: I’d describe what Carey is observing as the telegraph’s role in facilitating the economic colonization of the future.

...as the telegraph closed down spatial uncertainty in prices it opened up, because of improvements in communication, the uncertainty of time.

...the Chicago Commodity Exchange, to this day [1983] the principal American futures market, opened in 1848, the same year the telegraph reached that city.

...once space was, in the phrase of the day, annihilated, once everyone was in the same place for purposes of trade, time as a new region of experience, uncertainty, speculation, and exploration was opened up to the forces of commerce.

[The development of the futures markets] required that prices be made uniform in space and that markets be decontextualized. It required, as well, that commodities be separated from the receipts that represent them and that commodities be reduced to uniform grades.

...the growth of communications in the nineteenth century had the practical effect of diminishing space as a differentiating criterion in human affairs. What Harold Innis called the “penetrative powers of the price system” was, in effect, the spread of a uniform price system throughout space so that for purposes of trade everyone was in the same place. The telegraph was the critical instrument in this spread. In commerce this meant the decontextualization of markets so that prices no longer depended on local factors of supply and demand but responded to national and international forces.

Here of course we see the technological hyper-charging of the spatial market expansion observed by Polanyi as central to the early emergence of the spatial revolution (see here). This “decontextualization” of course is just a backhanded way of saying universalization – or at least homogenization. Just as the telegraph gradually eroded local distinctiveness in language, so it eroded local economy. It simultaneously integrated local markets into a national, and ultimately international market, while providing the parsed-down language of generalized, homogenized “objective” and “scientific” discourse that facilitated the reduction of all goods to commodity utilities. Even at this, though, those were not the only ways in which the telegraph eroded local identity, and temporalist dispositions. Another important impact of the telegraph was in the molding of standardized time zones – coordinated centrally, and administratively – eliminating unique local clock coordination.

While it was not the telegraph alone that led to the adoption of standardized clock coordination, it was certainly a direct influence in allowing telegraph offices to coordinate their own activities. But of course in facilitating the spread of both the railroad and standardized commodity markets, its indirect impact was even greater.

...standard time in the United States is a relatively recent invention. It was introduced on November 18, 1883. Until that date virtually every American community established its own time by marking that point when the sun reached its zenith as noon. It could be determined astronomically with exactitude; but any village could do it, for all practical purposes, by observing the shortest shadow on a sundial. Official local time in a community could be fixed, as since time immemorial, by a church or later by a courthouse, a jeweler, or later still the railroad stationmaster; and a bell or whistle could be rung or set off so that the local burghers could set their timepieces. In Kansas City a ball was dropped from the highest building at noon and was visible for miles around, a practice still carried out at the annual New Year’s Eve festivities in New York City’s Times Square.

...noon came a minute later for every quarter degree of longitude one moved westward, and this was a shorter distance as one moved north: in general thirteen miles equaled one minute of time.

When the vast proportion of American habitats were, in Robert Wiebe’s (1967) phrase, “island communities” with little intercourse with one another, the distinctiveness of local time caused little confusion and worry. But as the tentacles of commerce and politics spread out from the capitals, temporal chaos came with them.

As the railroads spread across the continent, the variety of local times caused enormous confusion with scheduling, brought accidents as trains on different clocks collided, and led to much passenger irritation, as no one could easily figure when a train would arrive at another town. The railroads used fifty-eight local times keyed to the largest cities. Moreover, each railroad keyed its clocks to the time of a different city. The Pennsylvania Railroad keyed its time to that of Philadelphia, but Philadelphia’s clocks were twelve minutes behind New York’s and five minutes ahead of Baltimore’s. The New York Central stuck to New York City time. The Baltimore and Ohio keyed its time to three cities: Baltimore; Columbus, Ohio; and Vincennes, Indiana.

Carey notes that despite the efforts of railroad and telegraph advocates (and no doubt many in the new, national commodity markets) to pressure the U.S. Congress to adopt standardized coordination of clocks across the country, for many decades there was fierce resistance to the proposal. While he never says as much, it seems more than plausible that it was precisely the temporalist personalities of the local communities across rural and small town America that rebelled at the railroad and telegraph’s grand standardization and homogenization project, which was yet another fractal in Schmitt’s spatial revolution (see here).

The railroads tried during that period to get Congress to adopt...a uniform time system, but Congress would not and for an obvious reason: standard time offended people with deeply held religious sentiments. It violated the actual physical working of the natural order and denied the presence of a divinely ordained nature. But even here religious language was a vanishing mediator for political sentiments; standard time was widely known as Vanderbilt’s time, and protest against it was part of the populist protest against the banks, the telegraph, and the railroad.

The changeover was greeted by mass meetings, anger, and religious protest but to no avail. Railroad time had become standard time. It was not made official U.S. time until the emergency of World War I. But within a few months after the establishment of railroad time, the avalanche of switches to it by local communities was well under way. Strangely enough, the United States never did go to 24-hour time and thus retained some connection between the diurnal cycle of human activity and the cycle of the planets.“

Not only did this eventual triumph of the spatial revolution constitute a major assault upon the culture and orientation (outward rather than inward) of America, and eventually the entire world, but it constituted as well a kind of quantum leap in both the force and dimensions subject to that revolution’s “spatialization”:

The development of standard time zones served to overlay the world with a grid of time in the same way the surveyor’s map laid a grid of space on old cities, the new territories of the West, or the seas. The time grid could then be used to control and coordinate activities within the grid of space.

When the ecological niche of space was filled, filled as an arena of commerce and control, attention was shifted to filling time, now defined as an aspect of space, a continuation of space in another dimension.

And while, as noted above, I think this use of the term “time” is unhelpful, especially for a scholar so influenced by Innis, this last passage of Carey’s is felicitous as a transition into our topic for the next post coming in this lengthy exploration of Schmitt’s spatial revolution. As we’ve seen, like Innis, Carey did appreciate that transmission, while analytically distinct, could not be historically insulated from the ritual, psychological, and cultural. Changes in the former inevitably entailed changes in the latter. And you'll recall that Schmitt too was keenly aware of the mental and cultural aspects of the spatial revolution (see here). And, eventually, inevitably such dynamics do introduce into Schmitt’s revolution entirely new dimensions of “spatialization.”

So, in the spirit of the door opened with Carey’s analysis of the impact of the telegraph, in the next post, we’ll explore a whole new frontier in the expansion of the spatial revolution. So, if you don’t want to miss that, and haven’t yet, please…

And, if you know of anyone who’d appreciate what we do around here, please…

Meanwhile: Be seeing you!

For example, see James W. Carey, “Space, Time, and Communication: A Tribute to Harold Innis,” in Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society, 2 edition (New York: Routledge, 2008).

Carey also captures this Innisian insight in distinguishing between what he calls a high and low communications approach. Compare the telegraph essay cited below with James W. Carey, “A Cultural Approach to Communication,” in Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society, 2 edition (New York: Routledge, 2008).

James W. Carey, “Technology and Ideology: The Case of the Telegraph,” in Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society, 2 edition (New York: Routledge, 2008).